On the evening of April 18, 1775, Paul Revere made his legendary ride to Lexington to warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams of potential arrest by the advancing British troops.

Also among the group, however, was a figure who is less widely known but their equal in terms of historical significance: the Rev. Jonas Clarke, at whose parsonage the American revolutionaries were gathered.

In his new book published by the History Press, “The Patriot Parson of Lexington Massachusetts: Reverend Jonas Clarke and the American Revolution,’’ Lexington historian Richard Kollen describes the clergyman’s central role in the town’s political, civic, and social life — including Clarke’s increasingly emphatic admonishments to parishioners to oppose imperial legislation in the years leading up to the war.

“Simply put, he wielded the most important political influence in the town in which the American Revolution began,’’ Kollen said of Clarke, a 1752 graduate of Harvard College who was pastor of the Church of Christ from 1755 until his death at age 74 in 1805. Clarke, who had 12 children with wife Lucy Bowes Clarke (a cousin of Hancock), was then laid to rest in the Old Burying Ground in Lexington.

This is the sixth book — and fourth about Lexington history — written by Kollen, a Quincy resident who has taught history in the Lexington public schools since 1974. While Clarke’s contributions have been previously honored with the naming of the Hancock-Clarke House and Jonas Clarke Middle School in Lexington, Kollen said he took on the project seven years ago to make Clarke’s name more recognizable outside the town.

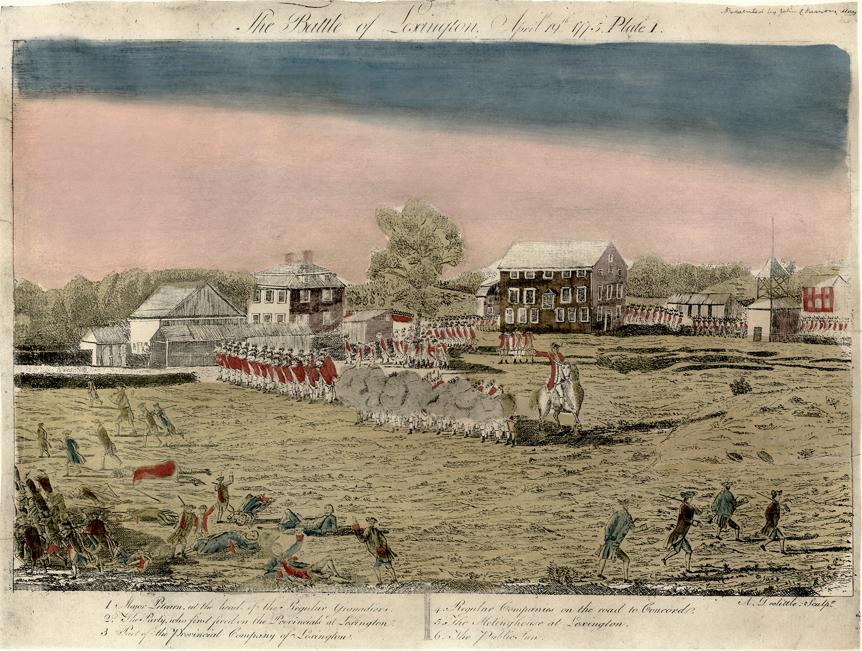

The 208-page book features 38 black and white images, including two on the front cover: a silhouette of the reverend, and the 1775 hand-colored engraving “The Battle of Lexington’’ by Amos Doolittle in which Clarke’s meetinghouse is visible.

Kollen also used Clarke’s letters, resolutions, and other political papers, three of his five almanac diaries, and 30 of the 2,238 original sermons cited in a log within the collection at the Lexington Historical Society. In honor of the one-year anniversary of the Battle of Lexington, for example, Clarke spoke out on April 19, 1776, of commemorating “the murder, bloodshed, and commencement of hostilities between Great Britain and America.’’

Kollen, who has also taught US history at Middlesex Community College and Northeastern University, noted it was customary at the time for politically inclined Congregational clergy to use their influence to support a particular viewpoint — which, in the Boston area, typically opposed British authority. In fact, loyalists dubbed a term for the phenomenon: the “black regiment,’’ in a nod to their black robes and perceived evil intent.

“In country towns in particular, the ministers were often the only well-educated and well-traveled people living there,’’ said Kollen, who has received numerous teaching awards along with the Massachusetts Historical Society’s Adams Fellowship. “They were very well steeped in political theory, and if they took an anti-imperial position — as Clarke did in his belief of basic, unalienable rights — they were likely to use it one way or another.’’

In this case, Kollen noted, Clarke’s role in Lexington’s political evolution during the 1760s and 1770s ultimately contributed to the beginning of the American Revolution.

Through his book, Kollen said he hopes readers gain a greater appreciation of local history, the number of people involved in making it, and how it can build to national significance.

“When you look at how one town can become radicalized, and the role that ministers played in people’s lives, Jonas Clarke is generally the authority,’’ he said.

“The Patriot Parson of Lexington Massachusetts’’ is available through the Lexington Historical Society Bookstore at lexingtonhistory.org/books.

Cindy Cantrell can be reached at cindycantrell20@gmail.com.