Video boards are a ubiquitous part of the sports experience nowadays. It’s practically a constitutional right to be able to view replays and relive moments right after they happened in an arena, stadium, or ballpark. Fenway Park, most revered for its age and patina of the past, was at the vanguard of the video age, 40 years ago.

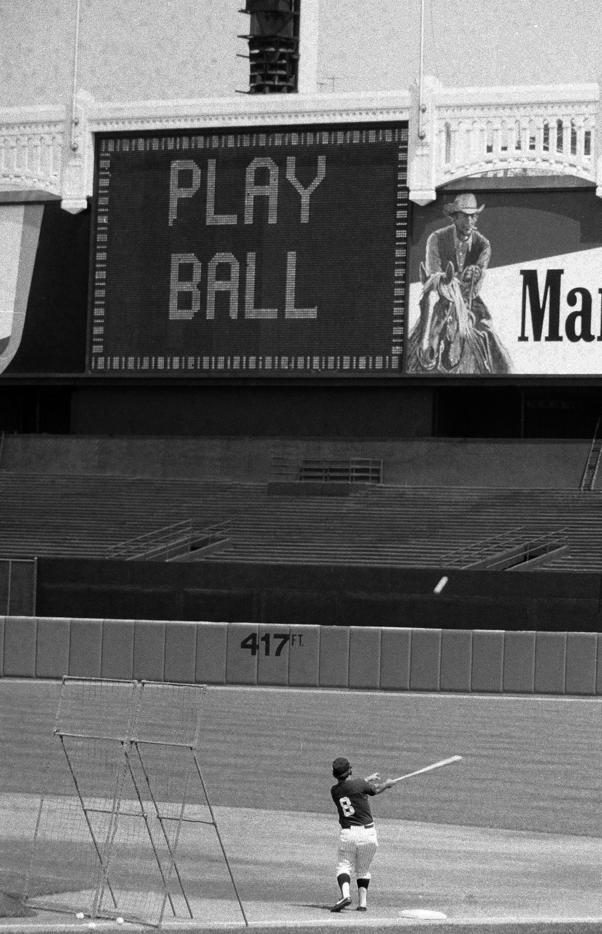

On April 13, 1976, Fenway became the first stadium in major league baseball to debut a video board. It was a 40-by-24-foot, black-and-white, Stewart-Warner Co.-manufactured screen billed as the Marvelous Message Board. Late, great Globe sports editor and columnist Ernie Roberts described it as “the biggest and most controversial innovation at Fenway in the Tom Yawkey era.’’

It cost $1.2 million. Sox general manager Dick O’Connell said the advertising featured on the screen would help “hold the line on ticket prices in the future.’’ The screen should have come with a built-in laugh track, apparently.

That original video screen in the center field bleachers is a fan-friendly footnote in the Red Sox-Yankees rivalry, which was renewed this weekend in the Bronx. It allowed the Red Sox to do something that didn’t happen very often in the latter part of the 20th century — beat the New York Yankees for a title.

In the closing days of the old Yankee Stadium, the Yankees touted that the remodeled Yankee Stadium had featured baseball’s first big screen.

Wrong.

Fenway’s big board debuted two days before the Yankees christened the renovated House That Ruth Built on April 15, 1976. Tiger Stadium in Detroit unveiled a board in 1976, too.

The race for replay capability between the archrivals wasn’t exactly the Space Race between the United States and the former Soviet Union, dubbed the Evil Empire by President Ronald Reagan long before the Yankees received the unflattering moniker.

But the bragging rights in this facet of the rivalry belong to Boston.

The man in charge of running the new curiosity in 1976 was 22-year-old Boston College graduate Jim Healey, who was working in the accounting department. Healey is better known today as the president of the Yawkey Foundations. He worked for the Red Sox for 31 years.

A panoptic view of play while attending a baseball game was a revolutionary and controversial idea in 1976, especially at Fenway Park. It involved tinkering with the look of the famed ballpark and adding a new instrument to the sacred soundtrack supplied by the faithful, organist John Kiley, and public address announcer Sherm Feller.

Healey’s roommate told him he was going to join a group protesting the addition of the new screen.

“I said, ‘We probably won’t be roommates anymore because I’m going to be running that board you’re opposing,’ ’’ recalled Healey.

“Back then if you did anything to the ballpark it was a big deal. People didn’t like change. Nowadays, it’s easier because people are accustomed to it. And ’75 was such a great season. It generated so much interest and some people didn’t want to see that change. That went away very quickly once people saw the board and people saw what a great amenity it was. Most people today couldn’t envision going to a sports arena or stadium without a video board.’’

Healey had started with the Sox as an usher in 1971 and worked on the grounds crew and in the ticket office.

When he heard after the 1975 season the Sox were planning an innovation, he marched into the front office and offered his video and computer experience from BC.

He got the job, even if no one knew exactly what the job was.

“I was always a techie,’’ said Healey. “I had been general manager of the radio station in school . . . It was a fun job. I really enjoyed it. It was learning a lot of new things. Being the first to do it was really special.’’

Healey and the big board were supposed to debut on April 12, 1976, but the Red Sox’ home opener against the Cleveland Indians was postponed because of inclement weather. It gave Healey more time and more anxiety.

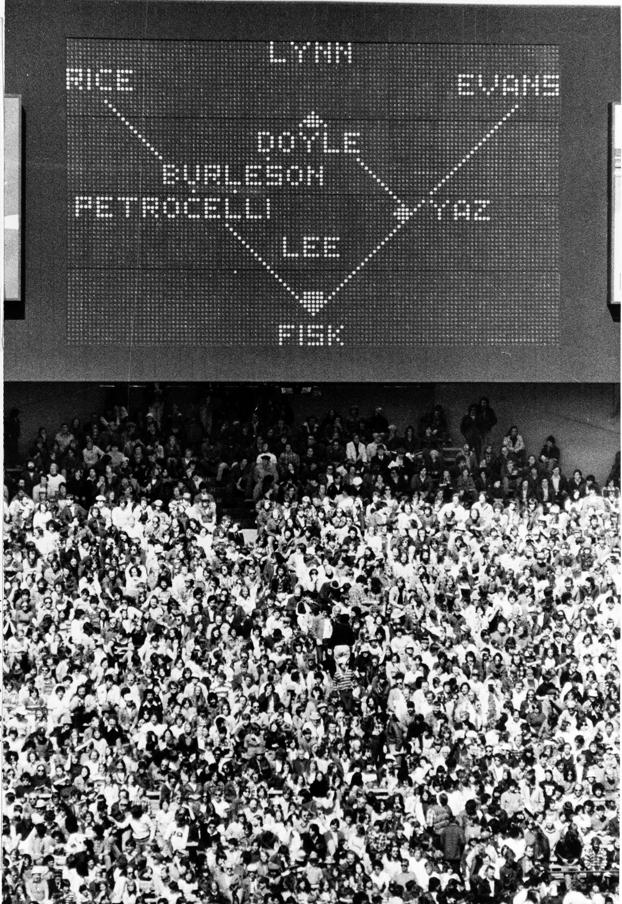

The first replay shown at Fenway Park was Jim Rice scoring a run. In the second inning of Boston’s 7-4 win, Carl Yastrzemski grounded to shortstop, and Rice came charging home from third. The throw beat him, but Cleveland catcher Ray Fosse dropped the ball.

Using the local television feed and ¾-inch video recorders, Healey was soon able to show many of the 32,127 in attendance why. Rice’s left cleat had clipped Fosse’s glove and cut Fosse’s exposed left forefinger. The crowd loved it.

The Indians didn’t. They complained, claiming that if a Cleveland player had slid into Sox catcher Carlton Fisk like that and it had been projected for the fans like a drive-in movie it could have sparked a riot.

But the board made an impression on the person who mattered most — the owner. After the game, Yawkey came into the office and startled the young employee.

“Jim, you did a great job today,’’ he told Healey. “Dick O’Connell didn’t really convince me to do this. I didn’t think it was the right thing to do, but the fans seemed to enjoy it. I’m convinced.’’

Yawkey would die of leukemia in July of that year.

Healey played some role in Fenway’s video presentation until he left the team at the end of the 2002 season as vice president of broadcasting and special projects.

The original screen was swapped for a color version in 1988. The Sox replaced the video board structure in 2011, when they installed a high-definition screen.

The video board wasn’t the only time in 1976 that the Red Sox beat the Yankees to the punch.

That season featured the infamous melee between the Red Sox and Yankees at Yankee Stadium, ignited by a home plate collision between Lou Piniella and Fisk.

It was a white-hot period of competition between the teams.

“We competed with the Yankees in a lot of areas,’’ said Healey. “We wanted to be better with our board.’’

Christopher L. Gasper can be reached at cgasper@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @cgasper.