NEW YORK — It is called the Heimlich maneuver — saving a choking victim with a bear hug and abdominal thrusts to eject a throat obstruction — and since its inception in 1974 it has become a safety icon, taught in schools, portrayed in movies, displayed on restaurant posters, and endorsed by medical authorities.

It is also the stuff of breathless, brink-of-death tales, told over the years by Ronald Reagan, Elizabeth Taylor, Goldie Hawn, Cher, Walter Matthau, Halle Berry, Carrie Fisher, Jack Lemmon, sportscaster Dick Vitale, television newsman John Chancellor, and many others.

Dr. Henry J. Heimlich, the thoracic surgeon and medical maverick who developed and crusaded for the antichoking technique that has been credited with saving an estimated 100,000 lives, died Saturday at Christ Hospital in Cincinnati after suffering a heart attack at his home Monday, his family said. He was 96 and lived in Cincinnati.

More than four decades after inventing his maneuver, Dr. Heimlich used it himself on May 23 to save the life of an 87-year-old woman choking on a morsel of meat at Deupree House, their senior residence in Cincinnati. He said it was the first time he had ever used the maneuver in an emergency.

Patty Ris, who had by chance sat at Dr. Heimlich’s table in a dining hall, began eating a hamburger. “And the next thing I know, I could not breathe I was choking so hard,’’ she said later. Recognizing her distress, Dr. Heimlich, 96, did his thing. “A piece of meat with a little bone attached flew out of her mouth,’’ he recalled.

While best known for his namesake maneuver, Dr. Heimlich developed and held patents on a score of medical innovations and devices, including mechanical aids for chest surgery that were widely used in the Vietnam War, procedures for treating chronic lung disease, and methods for helping stroke victims relearn to swallow.

He also claimed to have invented a technique for replacing a damaged esophagus but later acknowledged that a Romanian surgeon had been using it for years.

A professor of clinical sciences at Xavier University in Cincinnati and president of the Heimlich Institute, which he founded to research and promote his ideas, Dr. Heimlich was a media-savvy showman who entered the pantheon of medical history with his maneuver but in later years often found himself at odds with a medical establishment skeptical of his claims and theories.

Even the Heimlich maneuver, when he first proposed it, was suspect — an unscientific and possibly unsafe stunt that might be too difficult for laymen to perform and might even cause internal injuries or broken bones in a choking victim.

But the stakes were high. In the 1970s, choking on food or foreign objects like toys was the sixth-leading cause of accidental death in America: some 4,000 fatalities annually, many of them children.

A blocked windpipe often left a victim unable to breathe or talk, gesturing wildly to communicate distress that mimicked a heart attack. In four minutes, an oxygen-starved brain begins to suffer irreversible damage. Death follows shortly thereafter.

Standard first aid for choking victims, advocated by the American Red Cross and the American Heart Association, was a couple of hard slaps on the back or a finger down the throat. But Dr. Heimlich believed those pushed an obstruction farther down in the windpipe, wedging it more tightly.

He knew there was a reserve of air in the lungs, and reasoned that sharp upward thrusts on the diaphragm would compress the lungs, push air back up the windpipe, and send the obstruction flying out.

His solution — wrapping arms around a victim from behind, making a fist just over the victim’s navel and thrusting up sharply — worked on dogs. His ideas, published in The Journal of Emergency Medicine in an informal article headlined “Pop Goes the Cafe Coronary,’’ were met with skepticism.

Anticipating resistance from his peers, Dr. Heimlich sent copies to major newspapers around the country. Days later, a Washington state man who had read about it used the maneuver to save a neighbor.

There were other cases and more headlines, and Dr. Heimlich was on his way to celebrity.

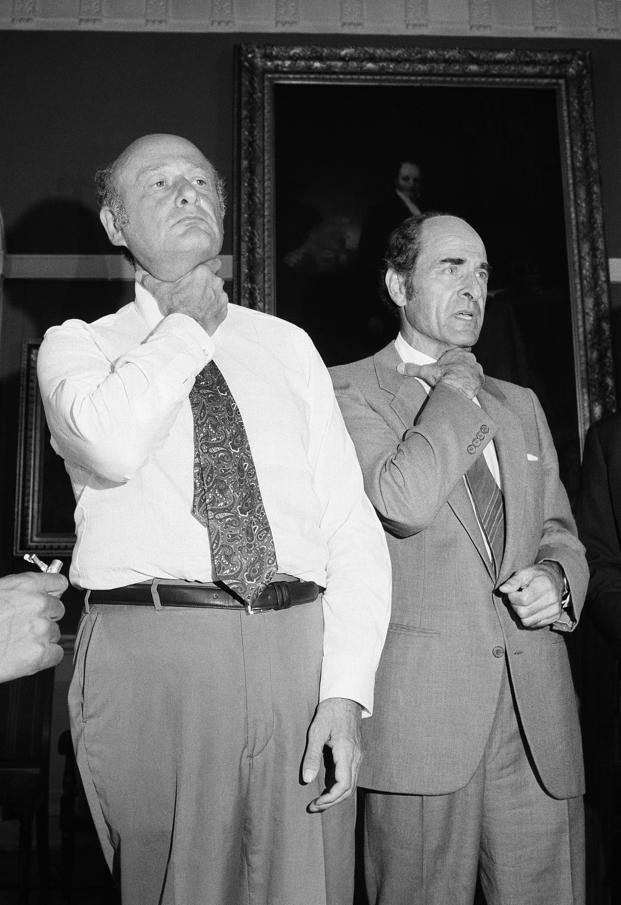

In 1986, a 5-year-old Lynn, Mass., boy saved a playmate after seeing the maneuver demonstrated on television. Two years later, then-senator John Kerry, Democrat of Massachusetts, used the maneuver to dislodge a piece of apple from the throat of a Republican colleague, Senator Chic Hecht of Nevada.

No one knows how many lives have been saved by the procedure, although reported choking deaths have declined since its popularization.

Some medical authorities have been wary, partly because it can cause injuries. From 1976 to 1985, the Red Cross and the heart association told rescuers to give back slaps first, and only then go to abdominal thrusts.

From 1986 to 2005, both recommended Heimlich thrusts exclusively. But in 2006, the guidelines essentially reverted to pre-1986 recommendations, dropped references to the Heimlich maneuver, and replaced it with the phrase “abdominal thrust.’’

In 1984, Dr. Heimlich, the recipient of many honors, won the Albert Lasker Public Service Award, one of the nation’s most prestigious medical science prizes, for a “simple, practical, cost-free solution to a life-threatening emergency, requiring neither great strength, special equipment or elaborate training.’’

Henry Judah Heimlich was born in Wilmington, Del., on Feb. 3, 1920, to Philip and Mary Epstein Heimlich. The family soon moved to New Rochelle, N.Y., where he attended public schools.

His father was a prison social worker, and Henry sometimes went along on his rounds.

At Cornell University, he received a bachelor’s degree in 1941 and a medical degree from Cornell Medical College in New York City in 1943. He interrupted an internship at Boston City Hospital to join the Navy in World War II.

He served with Chinese guerrillas in the Gobi Desert and Inner Mongolia. After the war he was a resident at several hospitals in New York City, and in 1950 he joined Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx.

In 1951, he married Jane Murray, the daughter of dance studio entrepreneur Arthur Murray. They had twin daughters, Janet and Elisabeth, and two sons, Philip and Peter. A full list of whom Dr. Heimlich leaves was not immediately available.

Jane Heimlich, who cowrote a book on homeopathy and wrote “What Your Doctor Won’t Tell You’’ (1990), about alternative medicine, died in 2012.