WASHINGTON — If the United States and China have succeeded at one thing this year, it is finding each other’s pain points.

An initial clash over tariffs has grown in recent months into a competition over which country can weaponize its control over the other’s supply chains.

China has clamped down on global shipments of rare minerals that are essential to building cars, missiles and a host of electronic products. The United States has in turn paused shipments to China of chemicals, machinery and technology including software and components to produce nuclear power, airplanes and semiconductors. As the conflict has escalated in recent weeks, it has caused Ford Motor Co. and other companies to suspend some of their operations.

Both countries are now trying to find a way to defuse the situation. Top-ranking officials from the two sides are meeting Tuesday for a second day of trade negotiations at Lancaster House in London, a historical site that has long been a stage for international treaties. They gathered just days after President Donald Trump held a 90-minute phone call with Xi Jinping, the Chinese leader — the first time the two heads of state had spoken directly since Trump returned to office in January.

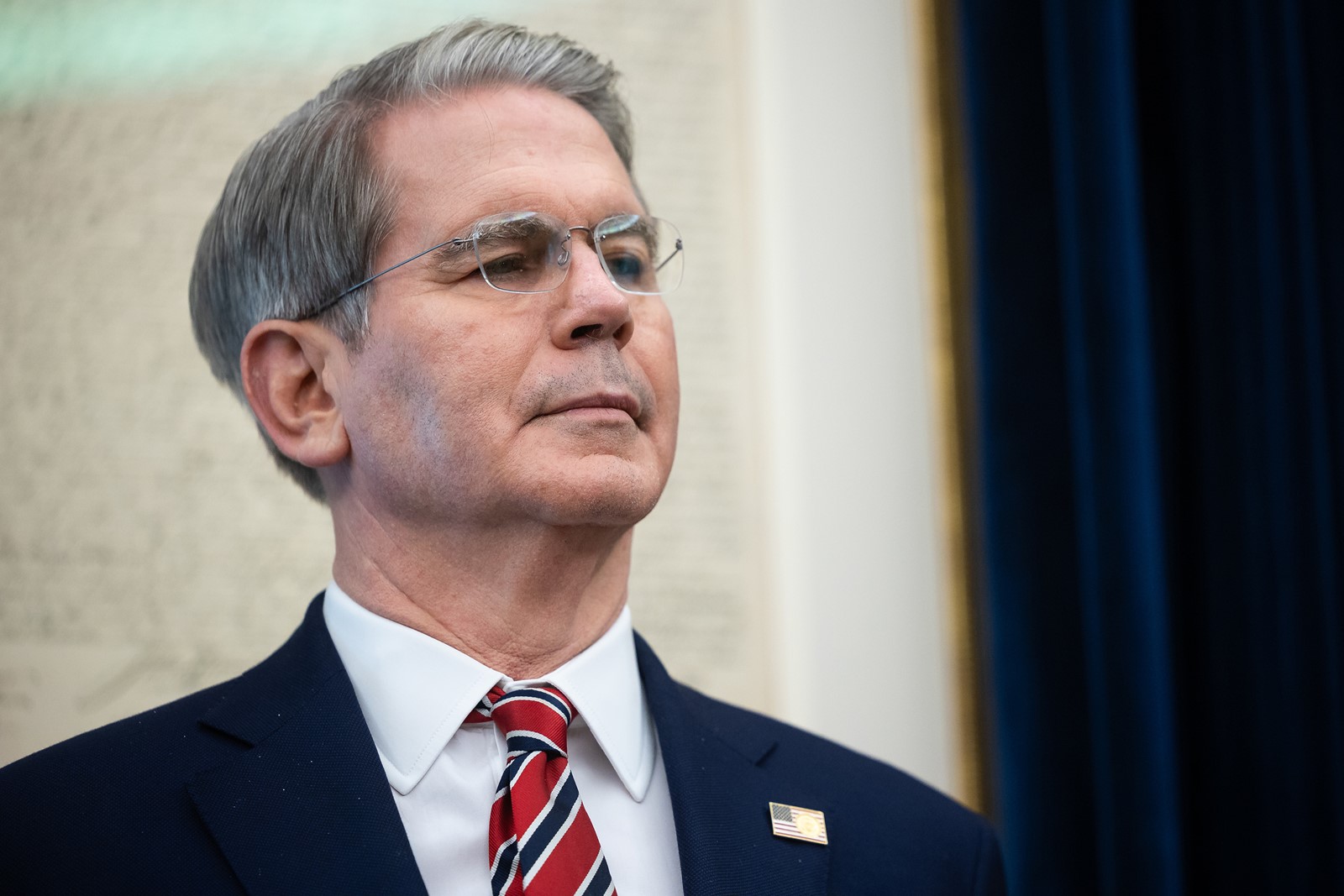

As he entered the building Tuesday, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said the talks were “going well” and that he expected them to run all day.

The haste with which the negotiations were arranged reflects the severity of the measures that both countries have recently adopted. After Trump ratcheted up tariffs on China in April, Beijing clamped down on exports of critical minerals and magnets, threatening to shut down operations by American manufacturers, defense contractors and others.

U.S. and Chinese officials struck a temporary truce in a meeting in Geneva last month to roll back tariffs and, Trump administration officials believed, to restart a steady flow of rare earths to American companies. But shipments of the minerals, and the magnets made with them, remain infrequent and tightly controlled. In late May, Ford temporarily closed a factory in Chicago that makes its Explorer SUV because of a lack of magnets.

In response, U.S. officials have tried to squeeze China by clamping down on exports to the country, including software for making semiconductors, gases like ethane and butane, and nuclear and aerospace components, people familiar with the bans said. U.S. officials also proposed bans on Chinese students in the United States as part of a coordinated effort to ramp up pressure on China before the call between Trump and Xi.

On the call, Xi warned that the leaders of the United States and China needed to “steer clear of various disturbances or even sabotage,” seemingly a reference to the idea that critics of China in Trump’s government had driven some of these efforts without his knowledge. But according to one person familiar with the efforts, the actions were done with Trump’s knowledge or at his direction.

In addition to Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who is leading the talks for the United States, and Jamieson Greer, the U.S. trade representative, the U.S. delegation includes Lutnick, who oversees the export controls. On the Chinese side, the negotiations are led by He Lifeng, the vice premier in charge of economic policy.

As the supply chain dispute has festered, Beijing has been setting up a system to require licenses to export seven rare earth metals and magnets made from them. American companies have been hoping this week’s talks could result in expedited licensing agreements for rare earth magnets, or even their inclusion on a “white list” that would allow the companies unfettered access.

In the lead-up to the talks, Lutnick asked automakers and other companies seeking rare earths and magnets for a list of their outstanding license requests to the Chinese, two people with knowledge of the discussions said. He planned to press Chinese officials to grant these licenses during the meetings.

Xinhua, China’s official news agency, published an editorial Monday about the country’s rare earth regulations, noting that “viewing these measures as mere short-term bargaining tools underestimates the strategic depth of China’s policy decisions.” It would be more “constructive” for Western countries instead to “focus on understanding and adapting to China’s new measures,” it continued.

A World Bank report published Tuesday underscored the toll Trump’s trade agenda was having on the global economy and projected output to slow sharply this year.

While Trump has occasionally mused about his interest in striking a broader trade deal with China, U.S. officials seem to have little optimism that the two sides could make progress toward a comprehensive agreement, especially as the supply chain dispute has dragged on.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE