Heather Martinez, as with many educators and parents of children with special needs, is concerned about what’s being done to the education system.

President Donald Trump signed an executive order Thursday calling for the shutdown of the Department of Education (DoE). The Michigan House Republicans echoed the move by adopting House Resolution 55, which supports the devolution of power from the federal government to states and urges Congress to support the effort. They also passed a budget that guts in Michigan that guts the state’s general budget, taking $5 billion from education funding.

That state bill is unlikely to pass the Democratic-led Senate or be signed by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, also a Democrat.

“We’re lucky in that we don’t rely on federal funding for our nonprofit,” said the CEO of Boldli Exceptional Youth Services (formerly Detroit Institute for Children), which is funded through private donations, charitable events and foundations.

Still, there’s that trickling down effect and when the funding disappears at one level it usually impacts others including the foundations that currently support the work of Bolkli, whose pool of talented special education teachers, psychologists, therapists and social workers are also utilized by local schools.

Supporters of the move put forth by Trump say it puts control of education in the hands of the states, who already distribute the dollars and that there’s no reason those funds including important grants and necessary functions cannot still be appropriated by Congress.

But how will it work?

“He has no plan in place to send the money to the states,” said Martinez, who worries about the grants her charity relies on.

Those funds enable Boldli to provide free afterschool tutoring for children with special needs, summer camps, therapy support and social and emotional learning.

The nonprofit began as an orthopedic clinic for children suffering with disabilities brought on by polio and tuberculosis in 1920, and from an institute that focused primarily on physical disabilities, evolved into an agency working with families, communities and centers across Michigan to help children with both physician disabilities and those you cannot see such as behavioral, cognitive and emotional disabilities.“We get a lot of grants and donations from foundations and private corporations,” Martinez said. “That’s how the whole entity has survived for more than 100 years.”

However, the people who process the grants worked in the office within the department.

Layoffs prior to the order directing Education Secretary Linda McMahon to close the DoE and return authority to the states included more than half of the department’s 4,133-member staff.

While the move was done to fulfill Trump’s campaign promise, a recent article by the New York Times said advocates and Democratic strategists have warned his aggressive move could backfire with voters. According to recent polling, six out of ten registered voters oppose the closure of the department.

Department fallout

It’s not just one department and thousands of American workers that were let go, many offices under the DoE and its contracts were terminated by Trump’s advisor, Elon Musk, and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), who dismissed them as “woke” and wasteful.

Among those gutted was the Institute of Education Sciences, which gathers data and research on the nation’s academic progress. Martinez knows of at least one study that was being done to determine why 80% of children with autism struggle with reading.

After graduating from The University of Michigan with a bachelor’s degree in development psychology, she became a mother and two years later found out that her little boy had autism.

So, she returned to school and embarked on a journey that not only led her to become a teacher, but to earn her masters degree in special education administration.

It’s this knowledge that led her to find the best available resources she could for her son, who is now 20-years-old and working on his teaching degree at Grand Valley State University and could become the next president of the Michigan Counsel for Exceptional Children, for which she once served.

Where will the next generation be without the amazing programs that have been developed over the years for children diagnosed with Autism Spectrum?

“I am deeply concerned about the significant reduction of staff and the executive order to eliminate the U.S. Department of Education,” said Judy Pritchett, a longtime educator in Macomb County and member of Michigan Board of Education. “While the order does recognize the fact that it will take an act of Congress for this to happen, we must understand that the uncertainty these actions create will have an impact on children throughout the country.”

Pritchett said over $2 billion is allocated to Michigan children every year from the department. About 212,000 students with disabilities and 681,000 students from low-income families are among the primary beneficiaries.

The funding is used to provide necessary services to special needs children and youth along with preschoolers in Head Start and children dealing with poverty, English language learners, homelessness and children and youth living in rural areas.

“We need to recognize the fact that threatening the programs and protections of our most venerable children will have a negative impact on them and their families,” Pritchett said.

Regina Weiss concurred.

“While Michigan families are focused on keeping up with rising costs and making sure their kids get a quality education, Republicans are focusing on dismantling the very systems that support them,” said the state Representative from Oak Park. “Trump’s executive order and the House of Republicans’ resolution backing it are absolutely not helping students, they’re about stripping resources from our schools and creating chaos for parents, students, teachers and communities.”

What’s next?

Molly Macek, education policy director at the fiscally conservative Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Midland, told The Detroit News it is difficult to predict the exact changes coming for students and schools after the firing of half the federal education workforce. But she said it is important for K-12 districts and colleges to understand the Trump administration does not have the power to close or dismantle the department.

“This reduction in workforce does not equate to a change in funding, that’s available for the programs that are in our schools,” Macek said. “Congress has not made a decision yet about the department’s budget and how those programs are funded. We’re not seeing any changes in how programs can be administered at the district level.”

The Individuals with Disabilities Act, which is a law passed by Congress to protect children, remains in place, said the Mackinac Center expert, noting that enforcement of that law could be handled by another federal department.

One rumored idea has the Department of Health and Humans Services handling it.

That has Martinez concerned for the future.

“We all know the DHHS is not functioning as it should be,” Martinez said. “They’re understaffed and overworked.”

Despite such concerns, Macek believes the changes being made will lead to a more decentralized education system, giving states more control over their students.

“So the positive of limited the control of the federal government is that states have greater control over the policies or even individual districts have greater control over the policies that they’re able to implement,” Macek said. “This gives greater autonomy to determine policies and implement policies that work best for their student population.”

Fighting back

The dismantling of the DoE can still be stopped by Congress, which is controlled by Republicans.

Following Trump’s firing of 50% of the DE’s workforce, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel also joined a coalition of 20 other attorney generals suing the Trump administration in hopes of stopping this week’s “total shutdown” of the DE.

“In 1975, President Gerald Ford (of Michigan) signed the first piece of legislation that opened the doors for children with disabilities nationwide,” Nessel said in a news release. “Since then students of all backgrounds have been guaranteed free appropriate public education.”

Nessel added the Trump administration’s dismantling of the Department of Education leaves the nation rudderless to provide the necessary funding, support and support that all 1.4 million Michigan students rely on.

Martinez said her organization will continue to support children with disabilities and the school districts that rely on the teachers, therapists, psychologists and social workers that they provide.

She is encouraging parents to reach out to their legislators and make their concerns known.

Martinez herself attended a town hall meeting organized by Detroit Public Schools Community District Superintendent Nikolai Vitti, who told The Detroit News special student programming and services will remain untouched by the changes for the rest of the school year. However, proposed federal cuts to Medicaid, being the agency that reimburses districts for special education services and other K-12 education funding, might lead to larger class sizes, reduced transportation and less staffing.

Last year the Macomb Intermediate School District received over $34 million in federal funds to support about 19,000 local students receiving special education services.

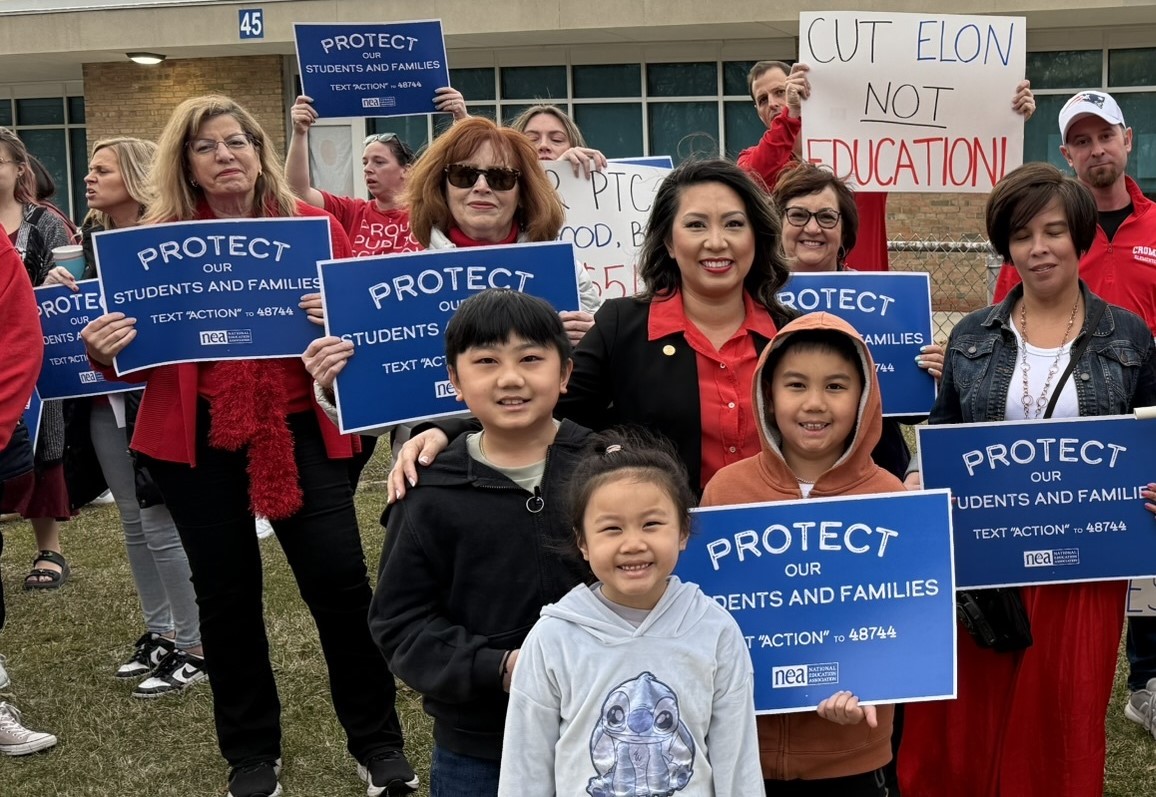

Warren Consolidated Schools received about $4.2 million last year in federal Title I funding and this past Wednesday saw hundreds of educators and parents from the district showing their support for the department that supports their kids.

Robert Callender, a high school chemistry teacher and president of the Warren Education Association, echoed the clarion call by Martinez. He said it is critical that parents and educators make their voices heard in support of protecting our neighborhood schools and providing every student, no matter their abilities or family’s income with the opportunity to get a good education.

“Dismantling the Department of Education would be devastating for local students with special needs and students from lower-income families, as our schools rely on federal resources to support special education programs, tutoring, school meals, and more,” he said. “This would cause permanent harm to Warren students, who need and deserve more support not less.”

Michael DeVault, superintendent of the MISD, said his staff will be monitoring the developments in Washington, D.C.

“Our parents are very concerned about the risk to special education funds in addition to any potential Medicaid impact on state budgets,” said DeVault. “Parents, the ISD and the state of Michigan have relied upon decades of support for special education from the federal government. So, parents are obviously experiencing apprehension and anxiety as any risk to this security of support is always taken seriously.”

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE