Any effort to change society in a huge way — or even to do something as vanilla as fighting poverty in a community that’s widely perceived as comfortable, like Orange County — depends on timing.

Consider:

A day before a few dozen Southern California nonprofits gathered for an event billed as the Anti-Poverty Summit, which was held Thursday at UC Irvine, new federal budget rules kicked in that will make it harder for low-income, homeless and disabled people to get food through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps.

It’s unclear if the new work-requirement rules for SNAP have been enforced; the federal government shutdown makes such information hard to get. But state budget experts project that as the SNAP rules take effect, they’ll initially push nearly 360,000 California residents (including about 30,000 in Orange County) out of the program, and by 2027, the experts add, the no-free-food-for-you rolls statewide could grow to more than 750,000.

And reductions at SNAP are part of a broader pattern.

One day after the summit, on Friday, federal officials said the government soon might stop paying for the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children. That program, also known as WIC, helps about 6 million Americans, mostly new mothers and their children, with food and breastfeeding assistance.

New attitude in D.C.

Many of the nonprofit leaders attending the event at UCI — advocates for the homeless and abused women and immigrants and the hungry, among others — say changes to SNAP and WIC and, literally, dozens of other federal policy shifts (less money to help low-income people pay their heating bills, cuts to programs for the disabled, firing the entire office of federal workers who track poverty) signal a new attitude in Washington.

Instead of trying to end poverty, as administrations of both major parties have pledged to do since the 1960s, at least some advocates say the second Donald Trump administration is openly hostile to lower-income people and to those who help them.

Which, in theory, might make this a wise time for the anti-poverty crowd to lay low.

Others, however, think it’s precisely the right time to take a stand on what, until recently, has been viewed as a bipartisan issue. Nonprofit advocates at UCI last week suggested federal rules and policies that seem to harm poor people actually might be an easy target to push against.

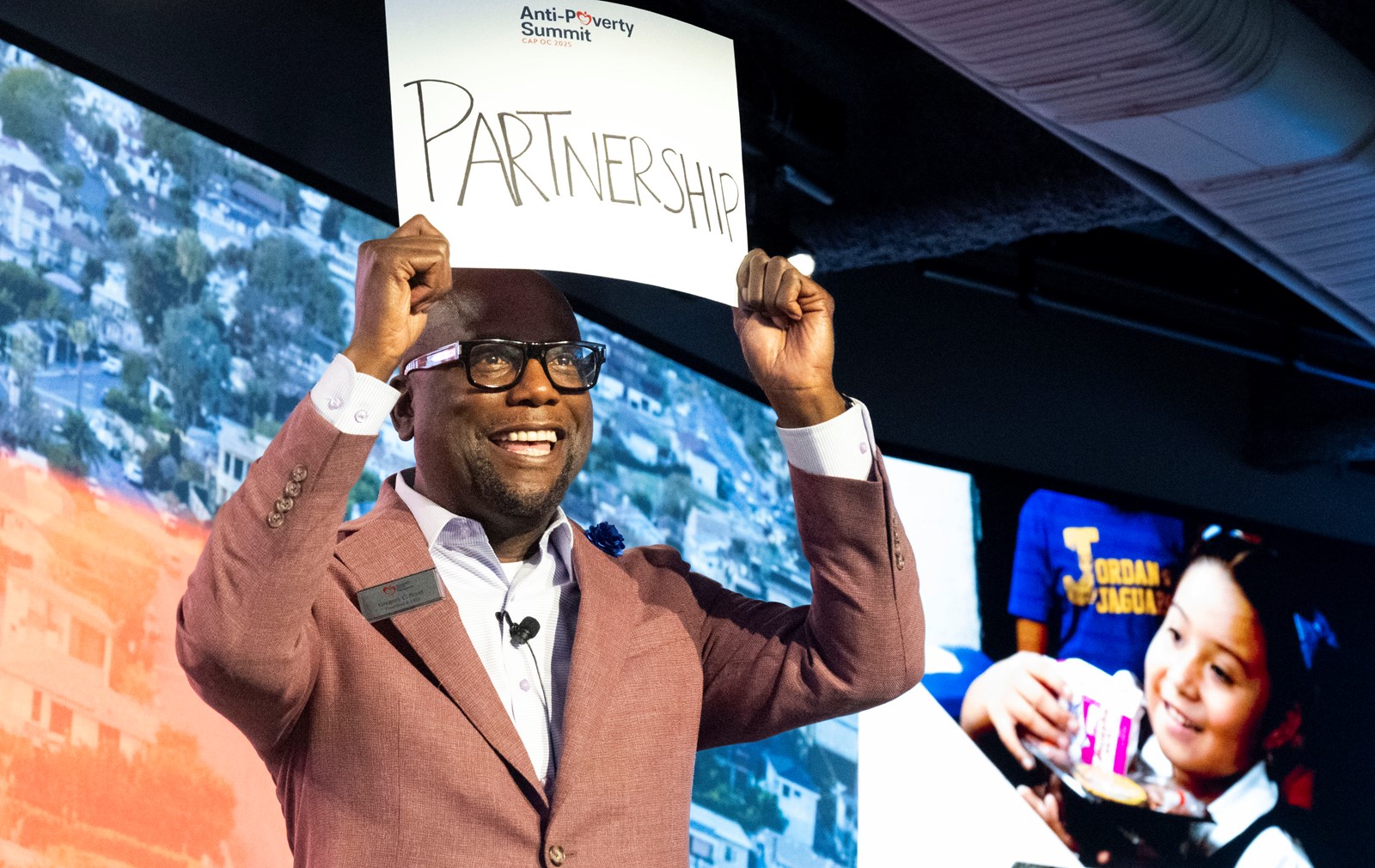

“I’m inspired by it,” said Gregory Scott, executive director of Community Action Partnership of Orange County, the Garden Grove-based group that sponsored the Thursday gathering.

“What we’ve seen gives me more reason to do the work I do,” Scott said. “That work is in jeopardy. And I don’t want it to be lost. If I can’t get inspired by that, and I don’t want to do more, than I’m not doing my job.”

Like many local nonprofit leaders who raise funds in a county that is politically purple, not blue or red, Scott doesn’t talk up partisan politics.

“We have support on both sides of the aisle,” he said. “We’re not a political organization; we’re a service agency.”

Community Action Partnership also is one of the biggest such agencies in the county. Operating as a sort of nonprofit conglomerate, CAP OC operates the Orange County Food Bank (which supports more than 230 food providers around the county) and a range of smaller programs that provide everything from mental health assistance and child care to financial literacy.

“We offer help for two sides of the house,” said Scott, who has led the group since 2018.

“We meet immediate needs, such as food assistance and mental health. And we meet long-term needs related to things like family empowerment and workforce development.

“Our work is about creating the ecosystem to help people stay out of, or emerge from, poverty,” he added. “That’s why we’re leading the effort to end poverty. It’s literally our job.”

At 60, Community Action Partnership also is old enough to have weathered — and thrived — even during wild political swings, almost always by staying out of the fray.

But the current moment is forcing a reevaluation, for Scott and for thousands of others.

On Wednesday, more than 3,700 nonprofit leaders from around the country signed an open letter condemning what they say are efforts by the administration to “intimidate and silence charitable groups through executive action.”

Those nonprofits, which back everything from environmental efforts and the arts to immigrant aid and housing, also said they will use a groupwide defense strategy, not unlike NATO, to marshal their collective resources to defend any nonprofit that in their view is unfairly sued or otherwise harassed by the federal government.

Scott’s name doesn’t appear among the signatures on that letter. And only a few groups from Southern California appear to be part of the effort.

Still, that doesn’t mean they’re staying out of politics.

In fact, Scott and others suggest that helping the poor isn’t as much a liberal or conservative idea as it is a traditionally American one. As a result, such events as the Anti-Poverty Summit — and the subsequent work to actually reach the goal of reducing poverty — become, in the current climate, subtle acts of resistance.

“If we sit back and say nothing, it’s a flaw,” Scott said.

Haves vs. have-nots?

Sitting back, and saying nothing, also is no longer tenable.

By any statistical measure, the goal of ending or even chipping away at poverty in Orange County is audacious. The county known in pop culture for surfing and upscale neighborhoods has, in reality, always mirrored — maybe even exaggerated — the nation’s ever-widening economic divide.

And a look at some federal and state data about Orange County tracked from the start of 2019 through the end of 2023, shows just how badly the local have-nots are being routed.

For example, during that five-year period, average household income in Orange County jumped by about 14.6%, to nearly $107,800. But at the same time, inflation in the Los Angeles/Orange County/Long Beach region jumped by 25.9%. That means by the end of the pandemic, the typical Orange County household had lost about 11% of its buying power.

For one group of people — homeowners — the blow was softened, at least emotionally, by rising equity. The median price of a home sold in Orange County jumped a whopping 53% during the period, to $1,267,500, according to the California Employment Development Department. That wasn’t pocket money unless you sold a home, of course, but it probably helped a lot of people sleep.

But that same trend kept renters up at night. The median rent in Orange County jumped by a third from the start of 2019 through the end of 2023, to about $2,600 a month, and the county started and ended the period as one of the nation’s 10 most expensive rental markets.

Add in unavoidable expenses such as gas, health care and tuition — all of which jumped faster than inflation — and you’ve got a growing feeling of economic frustration bordering on desperation. By mid-2023, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development seemed to make it official, declaring that a four-person household in Orange County bringing in $80,000 a year was “low income.”

More than 4 in 10 residents appear to be either at or near that line. In 2023, about 21.5% of all households in Orange County brought in less than $50,000 a year, while another 22.6% brought in between $50,000 and $100,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

It turns out, low-income isn’t always in the next town or even next door. Sometimes, it’s closer.

“We deal with poor people who don’t even know they’re poor,” said LaVal Brewer, president of Irvine-based South County Outreach, which helps people with food, housing and financial education. “Ending poverty in this county is going to require everybody to recognize it, first.”

The Anti-Poverty Summit didn’t broach many specific ideas to fix that. Instead, the focus was on inspiration and on getting smaller nonprofits that aren’t always asked for their ideas to join in the fight.

Scott agreed he’s still seeking concrete answers, but he believes some form of collaboration in which nonprofits could work and raise money together might have to become more than a buzzword.

For good or bad, that collaboration probably is coming.

The federal changes projected to squeeze low-income people also will mean less money for state and local governments, which provide a lot of nonprofit funding. That, in turn, could push hundreds of smaller nonprofits in the region to close or seek partners, even as demand for their services is on the rise.

“There has to be a model for doing business in the nonprofit world, just like in the private world, with acquisitions and mergers,” Scott said. “We have to adopt some of that to be taken seriously and survive.”

And, curiously, the same pressures roiling our culture might, in the long run, lead to actual change.

As he spoke at the Anti-Poverty Summit, Michael Tubbs, the former mayor of Stockton and candidate for lieutenant governor, noted that Scott’s group was founded in 1965, a year when American society seemed to be fraying.

“In 1965, Malcom X was assassinated,” Tubbs said. “In 1965, enforcement arms of the government, such as state troopers, (and) the National Guard, were used to brutalize and beat people who were protesting for the right to vote in Selma. In 1965, things looked eerily similar to the times we’re in now.”

But Tubbs noted that the Civil Rights Act also was signed in 1965. What’s more, even as strife continued to rip through the country over the next few years — riots, bombings, the 1968 assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy — racial and social progress also was made.

“That era gives us a good example and a mirror,” Tubbs said. “We have been here before.”