For members of the Bangles, the quintessential all-female band of the 1980s, “Walk Like An Egyptian” was an aberration — not just a departure from their rock-influenced roots, but running counter to it.

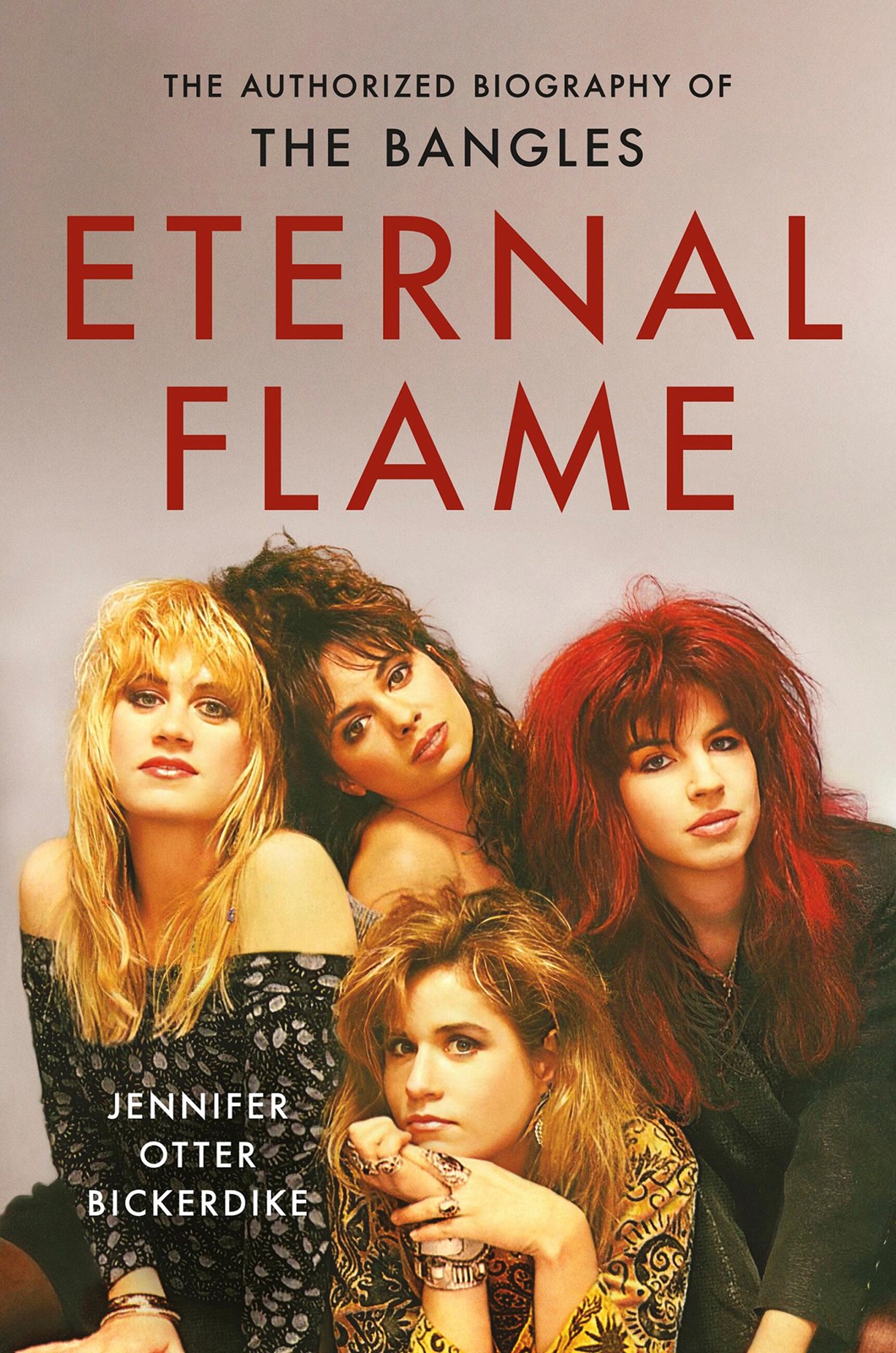

How the quirky single would help propel them to international fame and earn Susanna Hoffs’ flirtily darting eyes a place in music history is laid out in a new book, “Eternal Flame: The Authorized Biography of The Bangles.”

Author and rock historian Jennifer Otter Bickerdike takes “the girls” — Hoffs, sisters Vicki and Debbi Peterson, and Michael Steele — from their origins as a teenage garage band in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley to international stardom and to their painful breakup.

“Eternal Flame” uses first- person access to three of the band members (Steele declined to be interviewed), photographs, diary entries and other source materials to shed new light on a largely underappreciated band.

It gets off to a rocky start, in part due to excessive footnoting, and the storytelling can be at times choppy or long- winded, but the book leaves the reader with a poignant and more complex picture of the Bangles’ difficult road to success.

With “Walk Like an Egyptian,” “Manic Monday,” “Eternal Flame” and two other tunes, the Bangles became the only all- female rock band to sing and play their own instruments on five Top 10 Billboard hits.

As they cut their teeth with changing lineups and hard-won gigs, the Bangles encountered radio stations that would only play one girl band at a time and record executives who would encourage them to raise their hemlines.

And the press could be brutal, too — minimizing their musical talents while inventing rivalries with other all- female bands — particularly the Go-Go’s — or nonexistent romantic sparks with Prince.

Ultimately, the band met its end in 1989 amid exhaustion, internal rivalries and artistic differences with their record company. — Julie Carr Smyth, Associated Press

Indian critic Pankaj Mishra adds to the discourse on the Israeli- Palestinian crisis with “The World After Gaza,” a coolly argued polemic that sifts insights from the gore and chaos.

The idea for the book emerged during Mishra’s 2008 trip to Israel and Palestine, when he posed a pair of conjoined questions: Why would a historically oppressed minority in turn oppress another minority under their jurisdiction; and why would so many mainstream governments and journalists “ignore, even justify, its clearly systemic cruelties?”

“The World After Gaza” is his answer, its voice clear as a bell but with striking nuances. Mishra devotes most of his text to rationales for the Jewish state, weighing the pros and cons and considering familiar and lesser-known names.

Step by step, year by year, war by war: Mishra traces the unraveling of a noble ideal. The international order has gone the way of the dodo, he suggests, and Gaza is proof.

Mishra sees courage in college protesters who reject the uneasy roles of bystanders, confronting the moral complacency — complicity, in some cases — of their elders. But their efforts will likely fail, and the West will allow Israel to inflict violence on Palestine, bankrolled by the subjects of a transnational oligarchy.

This is depressing stuff, yet avoidable. Is sunlight the best disinfectant? “The World After Gaza” casts its audacious gaze on ashen ruins and human corpses, a debacle Mishra views as decades in the making.

The “stakes have rarely been higher,” he opines. “The atrocities of Gaza, sanctioned, even sanctified, by the free world’s political and media class, and brashly advertised by its perpetrators, have not only devastated an already feeble belief in social progress. They challenge, too, a fundamental assumption that human nature is intrinsically good, capable of empathy.” — Hamilton Cain, Minnesota Star Tribune

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE