High school journalists who put their professional counterparts to shame; environmental advocates who push back on polluters; an oddball teacher who leaves an enduring mark on his students: “Teenage Wasteland” has them all. This crowd-pleasing documentary, directed by Amanda McBaine and Jesse Moss (“Boys State” and “Girls State”), caters to multiple niches of moviegoers who enjoy rooting for the underdog. Even archivally minded cinephiles — the kind who get nostalgia pangs from watching long-shelved VHS tapes played anew — will find an itch scratched.

Titled “Middletown” when it showed at festivals this year, the movie memorializes the work done by a group of teenagers and their faculty adviser around Middletown, New York. In 1991, for a high school elective called Electronic English, they started a video project that ended up breaking real news and stretching throughout the decade over multiple cohorts of students.

At first, their impulse was simply to report. The teacher, Fred Isseks, had heard rumblings from a friend about the sludgy messes his neighbors had encountered. What was going on at a nearby landfill, which smelled, an alumnus recalls in the film, like “dead bodies and decay”?

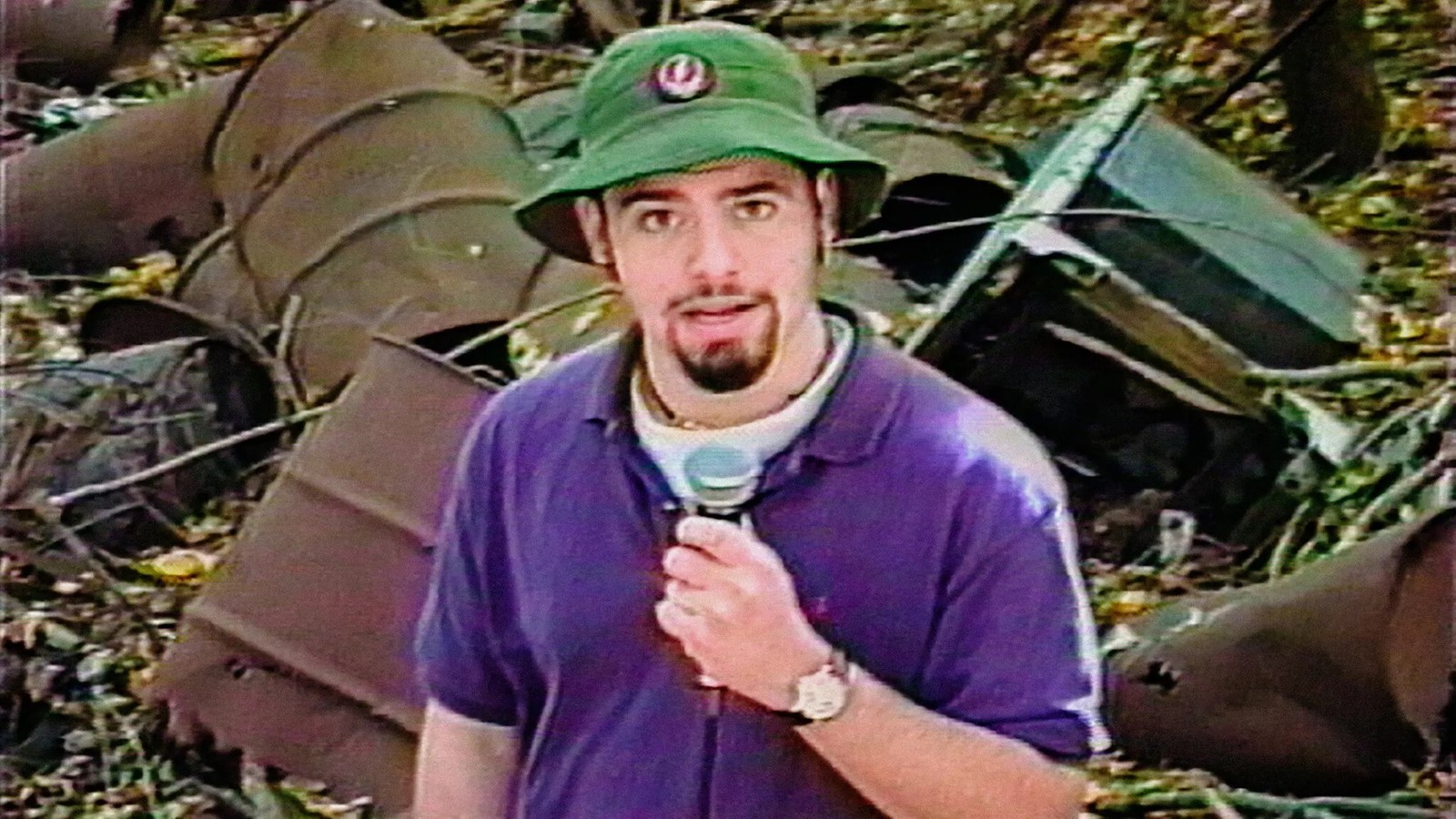

Proceeding with what Rachel Raimist, part of the original group of teens and now a TV director, remembers as a mixture of naivete and stupidity, the camera-wielding students made trips to the dump. (Their sleuthing ultimately seems to involve three landfills.) They uncovered an outrage that had implications for public health, politics, real estate and more.

McBaine and Moss take advantage of the irresistible opportunity to show the graduates, who today are around age 50, watching footage of their tenacious adolescent selves. The directors also spend ample time with Isseks, who, according to Raimist, was called nicknames like Hippie Fred and Crazy Fred at the time the course started. (We see an old clip in which Isseks is asked which historical figure he’d bring back from the dead; he chooses Karl Marx, to “check out all the predictions he made about late-20th-century capitalism.”)

While Moss and McBaine have found an entertaining way of organizing the material, the real treasure trove here consists of the students’ work. In interview after interview, they politely ask tough questions of adults who appear to be expecting softballs. When John Bonacic, a state Assembly member at the time, is asked about “illegal dumping,” he responds, “I let you come in here to talk to me about Earth Day.”

The present-day Isseks doesn’t recall any students chickening out after it was suggested — by a Deep Throat-like tipster, among others — that the pollution was connected to organized crime. Still, “Teenage Wasteland” might have done more to explore a conflict that Isseks alludes to: On one hand, it was his job as a teacher to encourage the students to stay on the story. On the other, it was his job as a guardian to keep them safe.

There are some points when McBaine and Moss might have clarified the chronology of the project. And I was alarmed to discover that a shot of a New York Times headline from 1995 — “High School Class Exposes Toxic Dump” — had been made to look as if the story had run across the top of page A1. (It was a below-the-fold article on B1 — which is still pretty good!) That’s the sort of needless manipulation that breeds mistrust in the whole film, and that you hope Isseks taught his students to avoid.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE