In chess, as in life, you are bound to make some mistakes.

That was the message Ed Bourgeois, access and outreach coordinator for the Minnesota State Chess Association, had for 32 inmates at the Minnesota Correctional Facility-Stillwater on Thursday morning, prior to their participation in the state’s first prison chess tournament.

“It’s your first time playing on the clock, and you’re going to blunder,” said Bourgeois, referring to the digital game timers required for tournament play. “It happens to the best players in the world. Please just keep your head about you. Your opponent is probably going to blunder one, too. Just don’t give up. Never give up.”

The inmates who had gathered in the prison’s recreation room at 8:30 a.m. spent the morning playing four official games of chess. The tournament, which took more than two years to plan, was open to all interested and eligible inmates.

Each player got to keep a chess board and pieces provided by the Gift of Chess, a nonprofit organization dedicated to bringing the game to incarcerated individuals. The top four finishers will play in a nationwide virtual chess tournament against other incarcerated players.

Warden Bill Bolin said playing chess helps people develop critical-thinking and problem-solving skills — and make positive choices.“Those skills are critical when we talk about transforming lives,” Bolin said. “Because we don’t want individuals who are continually having the same thoughts or making the same choices. We want them to look at things differently, and chess, really, if you’ve ever played chess, is a game of critical thinking and strategy and at times you’re looking two or three moves ahead.”

Impulsivity doesn’t work in chess, Bolin said. “You want to slow down your thinking, especially when you’re making some critical decisions. Then you want to come up with a positive choice.”

‘Chess is like life’

Inmate Hannabal Shaddai, 52, said he learned to play chess when he was a student at Laura Ingalls Wilder Elementary School in Minneapolis.

“My sixth-grade teacher taught me to play. Mr. Wendell. I’ll never forget him,” said Shaddai, who is serving a life sentence for murder. “He spent the last hour of school every day teaching students to play.”

When Shaddai started playing chess in prison, he said he remembered his teacher’s words of wisdom. “Mr. Wendell said that chess is like life,” he said. “You should know every move that you’re making. I equated that to my rehabilitation.”

The intellectual demands of the game appeal to Shaddai. “It makes you think. It makes you use your brain,” he said. “It’s a game of strategy, a game of tactics. You have to remember, ‘Why did I do that? OK, don’t do that. Yeah, let that go. Don’t worry about that.’”

Shaddai was paired with Richard Adams for his first game. Adams drew white, which meant he went first. Each player had 25 minutes on their clock to play the entire game.

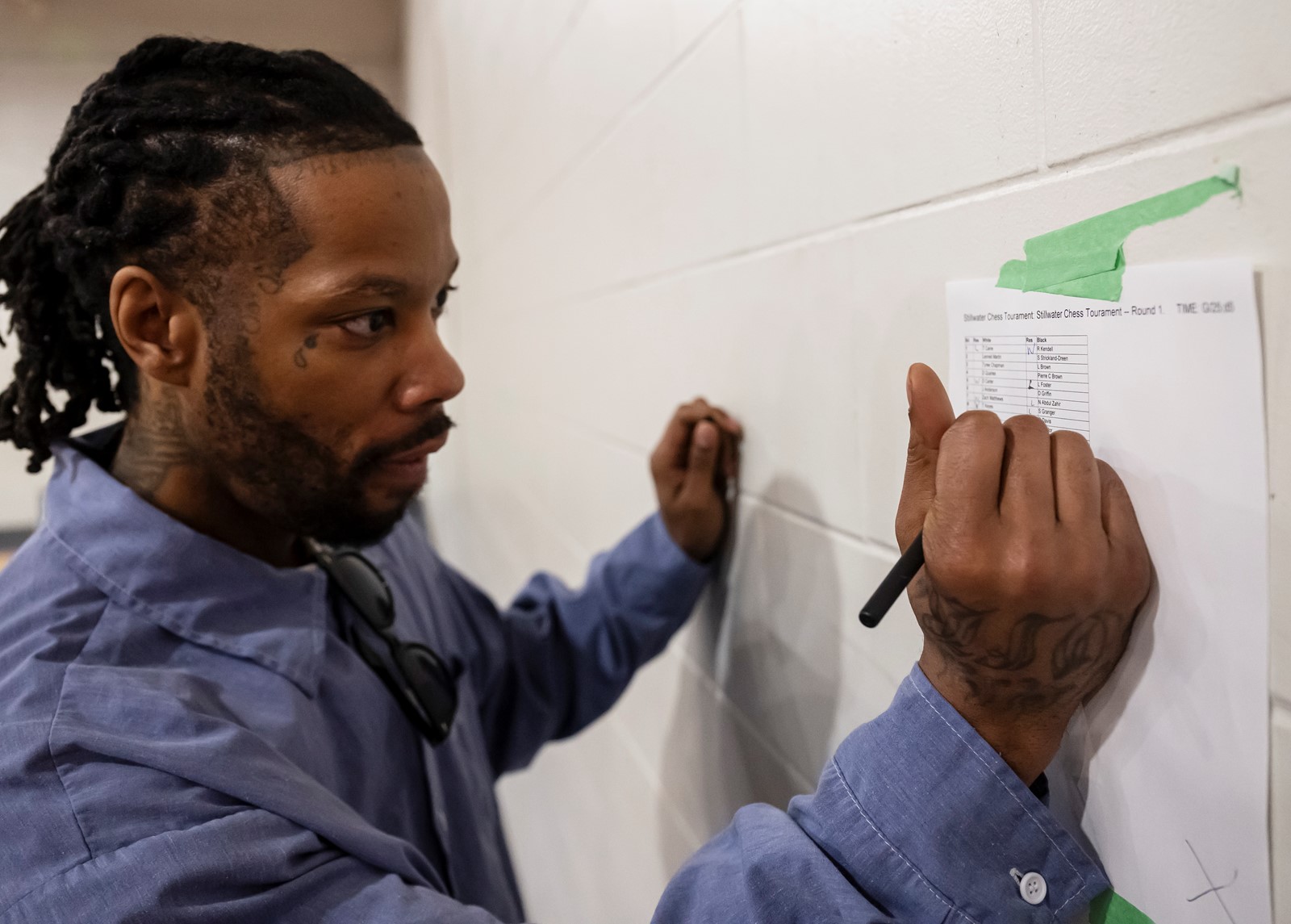

At Shaddai’s request, Dane Zagar, the tournament director, went over the “touch-move rule” just minutes before they started playing.

“Hey, y’all!” he yelled to the other inmates. “Listen up to the rules!”

Zagar, the president of Chess Castle of Minnesota, explained that if a player intentionally touches a piece on the board, they must move that piece if it has a legal move. “If you touch one of your opponent’s pieces first, you have to capture it,” he said. “If you have multiple options, you can capture it with whatever option you’d like to capture it with.”

Shaddai was happy to hear he had been playing correctly. “Some people don’t get the rules,” he said. “They play games, but they don’t know the rules.”

Trash talk

Shaddai beat Adams, but then Lon Newman, president of the St. Croix Valley Chess Club, teamed up with Adams to play Shaddai for a second time.

“Castle early,” Newman told Adams. “There are principles in the opening. One is fight for the center. Two is develop your minor pieces — your bishops and knights. And three is protect the king. So every move in the opening should be directed at one of those three things.”

Shaddai didn’t hold back from trash-talking his opponent. “I was a step behind him because I got black, but now I’m gonna step in front of him,” he said. “He gave it back to me. He should have castled before me. Now I’ve castled. My king is safer than his. His is still in the middle of the board.”

“I just don’t believe in the whole castle thing,” Adams said.

“So in boxing, you don’t believe in putting your gloves up? You believe in putting your chin out?” he said.

“I’m too fast,” Adams countered. “You won’t hit me in a boxing match.”

“That’s what that dude from Brazil thought,” Shaddai said, referring to MMA legend Anderson Silva’s loss to YouTube star-turned-boxer Jake Paul.

“You guys are the trash-talking champions here,” Newman said.

“You know what Mike Tyson says?” Shaddai said. “Mike Tyson said, ‘Everybody has a plan until you get punched in the face.’”

Before the tournament started, Newman encouraged the men to be on their best behavior. “If we screw it up now, we won’t be doing it again,” he said.

Welcome respite

In an interview with the Pioneer Press, Newman, who lives in Stillwater, said he hopes there will be future tournaments at the prison, which is located in Bayport.

“I’m hoping we can move forward,” he said. “I would have a monthly club meeting if I could get one.”

Inmate Robert Kendell-Bey, 44, thanked the organizers and said playing in the tournament was a welcome respite from everyday prison life.

“Any time that we can come together outside the madness and traditional modes of being in here is great for me,” Kendall-Bey said. “I’m all about cooperation and community, collaboration and mutualism. We look forward to moments like this where we can engage in community that’s outside the bounds of normal prison etiquette, so this is a moment of joy. Sincerely.”

Inmate Pierre Brown, 39, said he started playing chess in a juvenile detention center when he was 11.

“From that point on, I just always had passion for the game,” he said. “I love the game. It’s really like life. It’s like a war game, but it’s, like, you got to protect your king at all costs, so sacrifices must be made.”

Brown, who generally plays about five hours a day, said playing chess helped him grow and mature.

“It just helped me think about things,” he said. “Because I see in a game, when you make an impulsive move, then you have to suffer the consequences of that. You got to pay for it.”

Despite the amount of time he spends playing, Brown said he doesn’t dream about chess moves.

“I’m not gonna lie. I take my melatonin, and it just knocks me out,” he said.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE