By Ross Eric Gibson

Some of ZaSu Pitt’s friends in the Santa Cruz High School acting program were Lois Nelson and Carmen Ballen. They graduated in 1914, with Lois going into nursing school in San Francisco, and ZaSu to Hollywood in 1916. While there were disappointments, ZaSu found acting jobs were fun and paid well, and encouraged her friends to come down for a visit and have some fun doing extra’s work.

Lois Nelson came in 1918, seeking to do comedy, although studios preferred oddball comics, so her beauty and humor were contradictions. But Universal’s head, Carl Laemmle, hired Lois as a comedienne. She played a hotel maid, opposite a janitor played by an unknown Stan Laurel. Soon Lois had her own series. Stan Laurel had a pretend husband-and-wife vaudeville act with a woman shrewish on-and-off-stage. She was married, but her husband was overseas, so she relished their on-stage duo, and tried to get Stan to quit films. At last, she returned to her husband. Stan married Lois, and had a daughter named Lois in 1927. Laurel first paired with Oliver Hardy in 1927, and while the on-screen partnership prospered, the off-screen marriage did not. But they remained friends, and Stan built his former mother-in-law a house in Santa Cruz in 1934.

The writer

Meanwhile Carmen Ballen (daughter of Virginia Ballen) got her first writing experience on the Santa Cruz Surf, then was a feature writer for the San Francisco Bulletin, followed by the Examiner. Some of her articles were created from Hollywood publicity releases, which only told tidbits of a story. To get behind the scenes, Carmen went to Culver City in April 1920, seeing her old pals ZaSu and Lois, and sampled the life of an extra. Carmen became a publicist for Mary Pickford, Tom Mix, Will Rogers, Douglas Fairbanks, Jack Pickford (all of whom had filmed in Santa Cruz), as well as Mable Normand and other stars.

Carmen quickly moved to writing short stories in collaboration with one of the Goldwyn directors and writers, Arlo Channing Edington. Arlo had started as a studio reader, then with Carmen was responsible for rewriting scripts, doctoring stories and doing general editorial work. Carmen and Arlo worked the Mary Roberts Rinehart play “Empire Builders” into a movie featuring Cullen Landis, filmed in May 1920. Their collaboration styles were so compatible, they were married by September 1920, five months after meeting. They had a son, Channing, and a daughter, Mary.

Their first project as a couple was writing the 1920 novel “Brute McGuire,” which Fox Studios bought in November as a vehicle for actor William Russell. This sale gave them enough to buy a new car, and they immediately set to work on a sequel. Arlo’s story “Bare Knuckles” became another William Russell film, with Arlo assisting director James Hogan. Then Arlo helped San Francisco author Gertrude Atherton in presenting her first story written for film, “Don’t Neglect Your Wife,” while also assisting its director, Wallace Worsley. Atherton’s second film based on her best-selling book “Black Oxen” starred “It Girl” Clara Bow. Arlo went to San Francisco in 1924 to assist San Francisco film director Charles Swickard on his film “Build San Francisco.”

In 1922, Carmen wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle “Brains Better Than Beauty In Film Production of Today,” an article advising women to “cheer up! … The screen has passed the place where it only requires beautiful faces.” Recalling her 1914 acting experience in Santa Cruz, the article continued, “like the speaking stage, [the screen] requires brains, plus personality!”

Carmen visited the set of “Souls For Sale” at Goldwyn Studios, and interviewed Rupert Hughes, the writer-director-producer. It was based on his 1922 novel, then was serialized in Redbook. The story was how a runaway bride ended up in Hollywood filmmaking, with ZaSu one of the 35 cameos by Hollywood stars. Carmen described Hughes as “one of America’s foremost writers who has devoted the past year to the study of motion pictures,” detailed in his “Souls for Sale” movie with glimpses of the Hollywood movie industry that contributed to the flood of would-be starlets and extras.

Tarnished tinsel

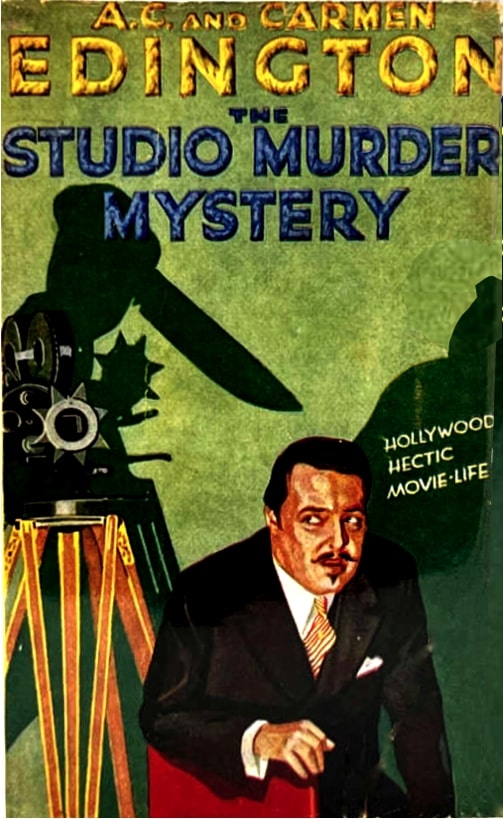

But Tinsel Town became tarnished by a series of scandals, amplified by fake stories in the yellow press. This included a woman allegedly raped by popular baby-faced comic Fatty Arbuckle in 1921, followed by the 1922 murder of actor-director Wm. Desmond Taylor, an unsolved cased which ended-up casting suspicion on many stars. Carmen had sought the “real” Hollywood for her news articles, but now saw more nuance in the setting, the people, and management. The Edingtons decided to write “The Studio Murder Mystery” set in the Hollywood world they knew.

Up to this time, detective novels followed the Sherlock Holmes style of scientific gathering and analysis of clues. But the 1920s was called The Lost Generation, feeling their youth was stolen by the war. Their uncritical trusting of “experts” had dragged them into a war where experts led futile cavalry charges against machine guns, mustard gas and aerial bombardment, ending up in trench warfare, disease and dismemberment. The Edingtons created Captain Smith as a hard-boiled detective, veteran of the last war, and formerly of the Los Angeles Police Department, where he worked fruitlessly on the Desmond Taylor murder. He embodied the veteran’s perspective, as an outsider fighting alone against a corrupt system.

The novel has a studio tour, which comes upon what looks like a corpse, but the tour guide says it’s only a dummy made to look like the star. A woman on the tour touches the dummy’s face, only to shriek in horror, for it is indeed the star’s corpse. The advent of sound led to soundstages so sound-proofed that nobody heard the victim scream. Captain Smith investigates, finding the studios a land of facades.

Some of Sid Grauman’s theaters resembled backlot sets, like the 1922 Egyptian Theater recalling Cleopatra films, and the 1927 Chinese Theater, each with forecourts and lavish auditoriums in Exotic Revival. (In 1903 Grauman ran the Santa Cruz Opera House for his Unique Circuit of film and vaudeville). These and other ornamental structures drew people from across the country to be part of the fantasy. Yet when Captain Smith entered the studio, the sets stood in eerie silence, reminding him of the war’s abandoned French villages, bereft of their street life and chatter. To Smith, even the Hayes Commission was just another facade.

The Edingtons wanted the three-part payoff for one story of serial, book and movie. First, in October 1928 they had their story published as a six-part serial in Photoplay magazine, offering a $3,000 reward to the person who first solved the mystery. Photoplay said this was “the first mystery story correctly to use studio technique and an absolutely realistic background as an integral part of the plot.” The popularity of the serial stirred Famous Players-Lasky to buy the film rights.

Paramount invested $1 million in a state-of-the-art soundstage, needing years to recoup its investment. The inaugural soundstage productions would be Paramount’s first musical, Marice Chevalier’s “Innocents of Paris,” as well as “The Studio Murder Mystery.” When they were about to start shooting, the as-yet unopened state-of-the-art sound stage burned down, thanks to all the flammable cork and felt sound-proofing in the walls. The studio alerted exhibitors the next day that they were committed to keeping the release date for “The Studio Murder Mystery.” The book came out and went into four printings in four months, with British publication rights to follow.

While the Edington’s were credited in the film, it is unclear if they were involved in the screenplay treatment. Director Frank Tuttle was worried the story had too much exposure, and that people wouldn’t want to see the story as written when they already knew who the murderer was. Ethel Doherty wrote a scenario that reduced the number of core characters to 10, turned the hard-boiled detective Smith into a dufus of a side character called Lieutenant Dirk, who is repeatedly mocked, and told that rough stuff is old-fashioned. A soft-boiled young screenwriter telling stupid jokes is made the idiot-hero, for the sole reason they wanted a Hollywood ending with a lovers’ kiss. The advertisements advised to come see if the murderer is the same as in the novel (it is), making enough name changes so the book is a useless guide to the movie. In the end, the movie was fair but erased all the character study and insight of the book.

Santa Cruz fanfare

The Edingtons had a summer home at Laurel in the Santa Cruz Mountains, thus able to keep in touch with family and friends. And while the film fell short of its potential, the Edingtons were glad to attend the local premiere at the New Santa Cruz Theater, if only for the distinction of bringing the first locally authored talkie to town. The Edingtons happened to tour the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose, which had been made a tourist attraction nine months after Sarah Winchester died in 1922. At the time, there was a myth that Mrs. Winchester continued building to house all the spirits killed by Winchester rifles. The Edingtons saw this endless labyrinth of rooms filled with spirits a perfect setting for their next Captain Smith murder mystery. They set it in Southern California, where a movie company staged a world war battle scene next to the mansion. The story was called “The House of Vanishing Goblets” (renamed “Murder to Music” for the British edition), “Written by movie people about the movie world.” It was serialized in Detective Book magazine and printed in 1930.

Then in 1931, Vitaphone hired S.S. Van Dine (creator of detective Philo Vance), to write 20-minute murder mysteries starring Dr. Crabtree. One in 1932 happened to be called “The Studio Murder Mystery,” having lifted title, plot and incident. The Edingtons sued Vitaphone and Van Dine for $500,000 but unsuccessfully. The Edingtons wrote two more novels, “The Monkshood Murders” in 1931, and “Drum Madness” in 1934, before their writing career ended in divorce. Carmen returned to Santa Cruz, where she donated a complete set of her novels to the Main Library. She became a member of the Third Order of St. Dominic (a lay Dominican), associated with Dominican Hospital. Arlo died in Los Angeles on Nov. 15, 1953, and Carmen died June 28, 1972, in a Santa Cruz convalescent hospital, and was interred at Holy Cross Cemetery.

In 2021, Justin Gautreau wrote in “The Last Word: The Hollywood Novel and the Studio System” (Oxford University Press) that the 1929 “Studio Murder Mystery” and 1931 “Death In a Bowl” shows when the hard-boiled detective style entered the literary depiction of the film industry. Gautreau believes two 1939 novels, Raymond Chandler’s “The Big Sleep” and Nathaniel West’s “The Day of the Locust,” were inspired by these earlier forgotten novels of hardboiled Hollywood.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE