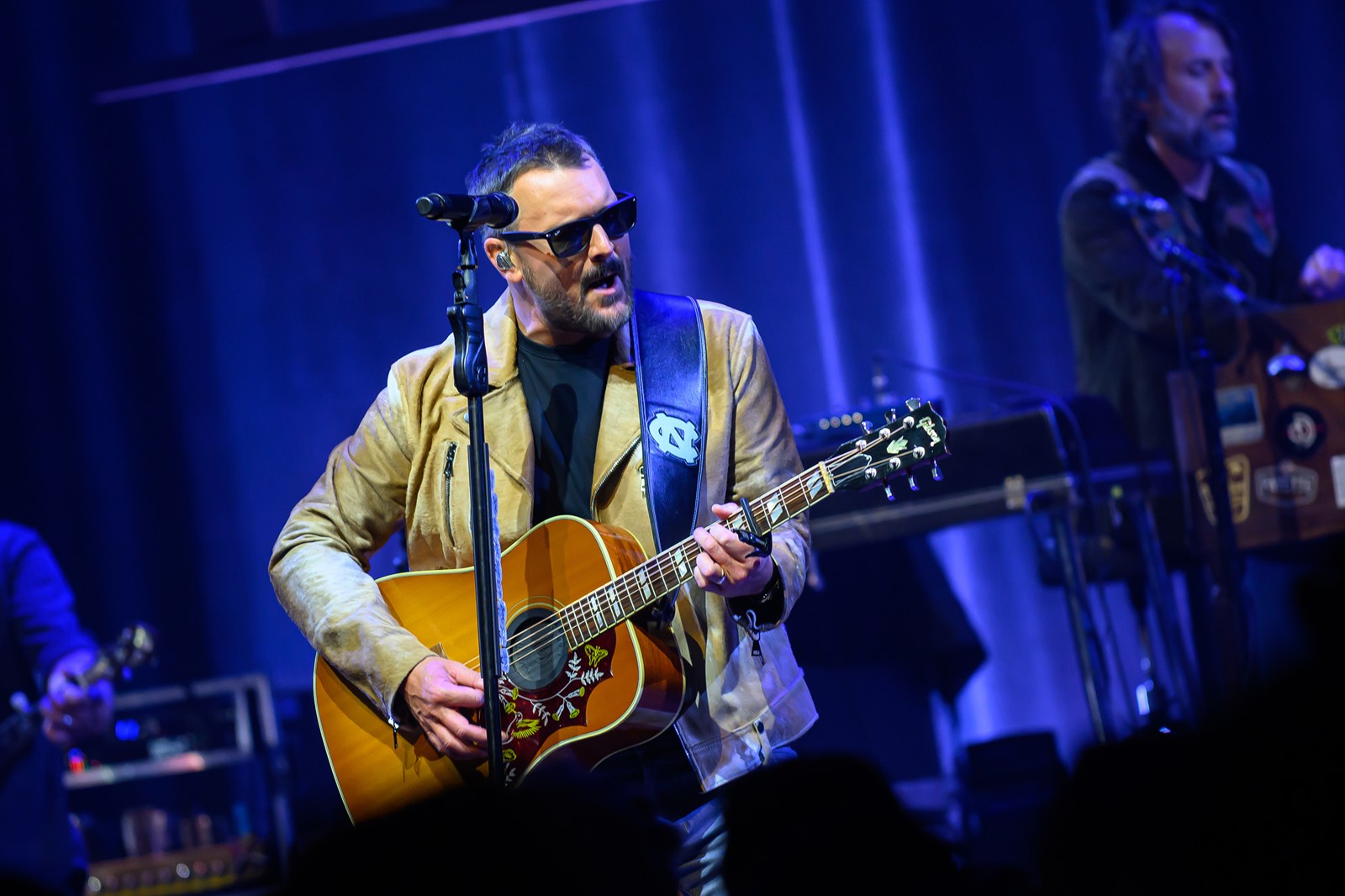

Nearly 25 years after he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, to make it as a country musician, Eric Church can count among his achievements 11 No. 1 country radio hits, five platinum-or-better albums, four CMA Awards and one six-story bar in Nashville called Chief’s.

Chief’s is just one of several business pursuits Church has undertaken lately, along with a line of whiskeys, co-ownership with Morgan Wallen of the Field & Stream brand and a minority stake in the NBA’s Charlotte Hornets. Yet recently the singer and songwriter, 48, returned to music with “Evangeline vs. the Machine,” his first album since 2021.

Produced by his longtime collaborator Jay Joyce, “Evangeline” moves away from the hard-rocking sound of earlier tunes like “Springsteen” and the weed enthusiast’s “Smoke a Little Smoke” toward a lusher, more orchestral vibe complete with strings, horns and a choir. “Johnny” is a kind of response song to the Charlie Daniels Band’s 1979 “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” while “Darkest Hour” offers help to someone in need.

The LP, which closes with a spooky rendition of Tom Waits’ “Clap Hands,” follows Church’s controversial headlining performance at 2024’s Stagecoach festival in Indio, where he and more than a dozen gospel singers blended the singer’s originals with spirituals like “Amazing Grace” and “I’ll Fly Away” and far-flung covers including Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” and Snoop Dogg’s “Gin and Juice.”

This interview with Church has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: What are the headaches you’ve run into as a business owner with Chief’s?

A: There’s been a bunch of those. I think just managing the messaging of why we’re different than other places. Listen, it’s been a roaring success … But we’re leaning into songwriter shows and shows by upcoming artists versus being somewhere to hear “Friends in Low Places” and get blackout drunk. The biggest challenge is just trying to make sure that people know what it is when they walk in the room.

Q: Any entrepreneurial models in your mind?

A: Jay-Z’s done a great job. When I did the national anthem at the Super Bowl with Jazmine Sullivan (in 2021), I remember I was like, “How does all this work?” And they said, “Jay-Z runs it.” I went, “What do you mean?” They said, “Jay-Z runs the entertainment at the Super Bowl.” OK, well, that’s (expletive) cool.

I’m in the Hornets with J. Cole — he’s another guy that’s done a really good job. Artists who get to a high level, they have these opportunities because they have the Rolodex. They meet people at shows, they meet people backstage. For me, I play golf with ’em.

Q: Couple of questions about Stagecoach last year. It was a polarizing gig.

A: (Expletive) that — it was great. PBS did a documentary, and there’s a moment midway through the show where you can actually see me start to grin. I’m like, this is going interesting. But as soon as it was over, I went back and listened to “Springsteen” a cappella in 30-mile-an-hour winds that night, and I knew it was good. If it wasn’t good, I would’ve had a problem. I kind of knew going in: This is probably not the place for this show. I’d played Stagecoach five or six times — you know there’s gonna be 30,000 TikTokers out there on people’s shoulders trying to take pictures of themselves. But I did it because it was the biggest megaphone, and it would get the biggest reaction.

Q: I got the impression that one of your goals with the performance was to draw attention to the Black roots of country music.

A: Sure. I was trying to show an arc musically — that this goes way back. I was trying to show where it all began. And I mean, maybe it was a little bit of a “(expletive) you.” I know we ran people off. But it wasn’t for the people that left — it was for the ones that stayed. I got a text from Lukas Nelson the following day. He was there with his surf buddies. He said, “We came in from Maui, and I just want to tell you that reminded me so much of my dad.” He said, “I put my arms around my buddies, and we all sang along.” I thought, well, he probably had plenty of room.

Q: I hear “Evangeline vs. the Machine” as being on a continuum with Stagecoach.

A: Yeah, but I’ll tell you where it started. Trombone Shorty came and played a show with me in New Orleans on the Gather Again tour (in 2022), and we ended up in the dressing room after and got in this incredible conversation about brass instruments and string instruments and the history of music.

Later he invited me to come play this show he does during Jazz Fest. There were probably two white people onstage that night: me and Steve Miller. So we do my song “Cold One” and (the Beatles’) “Come Together.” I’ve done “Cold One” a thousand times, but I had never done “Cold One” like that. It was a Black New Orleans band with horns and background singers and a violin player — not Juilliard violin but like a janky New Orleans violin. The dude had the damn thing on his shoulder, not under his chin. Everything was wrong for what that song is. I’m not convinced anyone even knew the song (laughs). But we found our spot in the middle of it, and it was killer. I flew home thinking: I want to do a record this way.

Q: Your falsetto in “Darkest Hour” — it’s almost uncomfortably vulnerable.

A: The song actually started three or four keys lower. But I was listening to Jim Ford and Sly & the Family Stone — honestly, I was thinking about Andy Gibb — and I just kept moving it up. I was incredibly insecure the first time in the studio, but I think that insecurity is what led to the authenticity of the emotion.

Q: You’ve said you wrote “Johnny” after the Covenant School shooting in Nashville in 2023. Do you envision the song reassuring a listener or making them angry?

A: Maybe both? The hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life is dropping my boys off at school the day after the shooting. I sat in the parking lot for I don’t even know how long because I didn’t know what to do. Do I stay here just in case? Not like I could do anything. But just to be close. And for whatever reason, Charlie Daniels came on. What hit me was that the devil was not in Georgia — he was here in Nashville.

Q: Why finish the record with a Tom Waits cover?

A: I had four years off (between albums), and I wrote a ton of songs. And a bunch of them are hit songs. I don’t mean that arrogantly — I just know after this amount of time that they’re hit songs. But some of them didn’t work with the room and with the instrumentation. We were going in (the studio) at 10 o’clock the next morning, and I was watching some show on Netflix, and “Clap Hands” came on. All of a sudden, I was like, “Oh ...” I paused it, grabbed my guitar, laid down just me with the riff and sent it to Jay. I said, “What about this?” He goes, “See you at 10,” and we cut it the next morning.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE