A butterfly flits past the window at the visitor center at Castlewood Canyon State Park, near Franktown, where dozens of volunteers have gathered to learn about Colorado’s declining butterfly population and how they can do their part to save it.

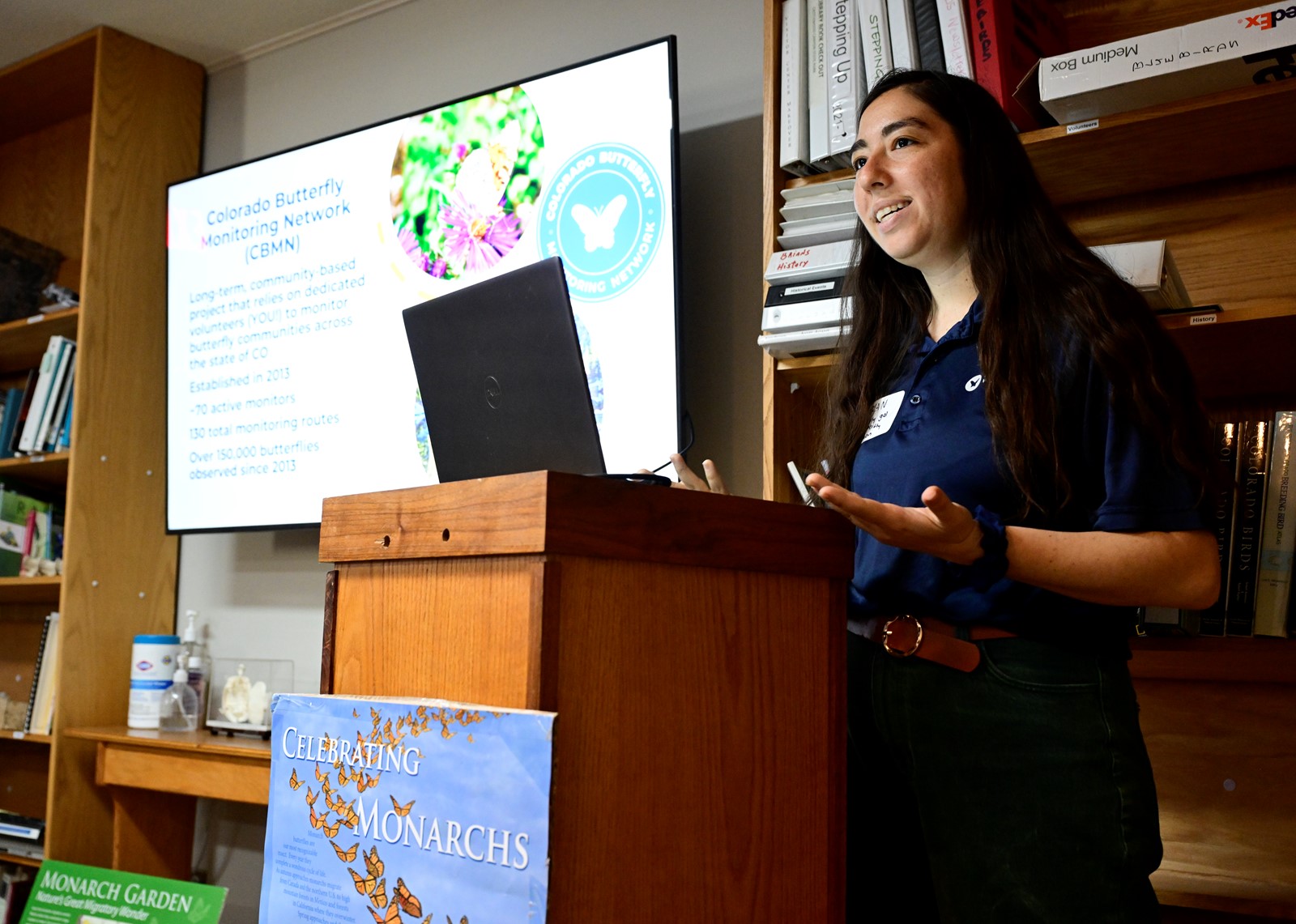

Shiran Hershcovich, a lepidopterist at the Westminster-based Butterfly Pavilion who’s leading the Saturday morning training, ushers the group outside to watch the mourning cloak butterfly as it settles on a blooming tree.

It lightly beats its wings until someone shuffles too close, startling it back into the sky.

Now, more than ever, scientists are calling for volunteers to help gather data on butterflies so organizations know where to focus resources to save the rapidly disappearing insects, Hershcovich said. Some volunteers undergo official training, but anyone can contribute just by posting photos online.

North American butterfly populations have declined by more than 22% over the past two decades, according to a study recently published in Science. Colorado saw approximately the same levels of loss, Hershcovich said. The national study combined 20 years of data from 35 community science programs across the country, including the Butterfly Pavilion’s Colorado Butterfly Monitoring Network.

An average loss of 1% each year might not sound like a lot, but it dramatically affects butterfly populations, Hershcovich said.

“The results were pretty grim,” she said. “We’re really at a critical point where we can either work hard to turn those numbers around or lose our butterflies.”

People-powered science

The first step is knowing where to direct resources and action, Hershcovich said. That’s where volunteers come in.

Cindy Cain, a nurse practitioner at the University of Colorado, was hiking in Jefferson County’s Reynolds Park five years ago when she saw a woman with a clipboard looking around. One conversation, one year and one training later, Cain had her own clipboard and was officially part of the Colorado Butterfly Monitoring Network.

She said she started with one trail but “just kept on accumulating routes.” She now monitors more than a dozen different routes for the network throughout the season.

“I know that it’s not everyone’s jam, but it makes my heart sing,” Cain said.

The monitoring network started with five volunteers in 2013. It reached nearly 100 volunteers across 12 Colorado counties in 2024 and it trained an additional 71 in 2025.

As of October, the end of 2024’s monitoring season, the network of Colorado volunteers had spent nearly 4,900 hours on trails across the state and documented more than 144,000 butterflies since its 2013 kickoff.

Change happens when everyone becomes involved in the conversation, Hershcovich said. It’s not limited to entomologists and other scientists — everyone has a stake in the game and the power to help.

“There’s a growing sense of ‘What can I do? How can I make a change?’, which is really empowering,” Hershcovich said. “(Volunteers) help us gather data and inform those collective pictures of what’s going on with the butterflies.”

Butterflies at risk — in Colorado and nationally

The mountain-prairie region that encompasses Colorado is seeing the second-most-severe annual butterfly declines and some of the most rapidly warming climate, according to the national study in Science.

“Places like Colorado are already dry,” said Ryan St Laurent, an evolutionary biologist and entomologist at the University of Colorado. “With increased droughts that we’re seeing with climate change, it’s exacerbating the existing problems that we’re already having with butterfly decline.”

The impacts of widespread butterfly loss and other invertebrate insects are almost unthinkable, St Laurent said.

“They pollinate plants, and they basically fill every ecological role you can imagine in terrestrial environments,” St Laurent said. “When you’re seeing declines, even if it’s a percentage here, a percentage there … we are going to be feeling the impact of that in ways that we probably don’t even realize yet.”

The extent of the loss varies across butterfly species and regions, but the overall theme is the same: Butterflies are in danger, Hershcovich said.

“It’s a complex picture of ups and downs, but what we do know for certain is that, overall, we are losing more butterflies than we are gaining,” she said. “It’s a pretty scary picture.”

Colorado’s diverse wildlife habitats are home to more than 250 types of butterflies, about a third of the species found in North America.

The Colorado Butterfly Monitoring Network has captured data on 173 of those, Hershcovich said.

Most of Colorado’s butterfly monitors are concentrated in the Front Range, so the network’s data on butterflies native to Colorado’s Eastern Plains or high mountains is sparse, she said.

But the network will never turn away a volunteer, no matter where they’re based, Hershcovich said. More eyes are always needed, including across the Front Range.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE