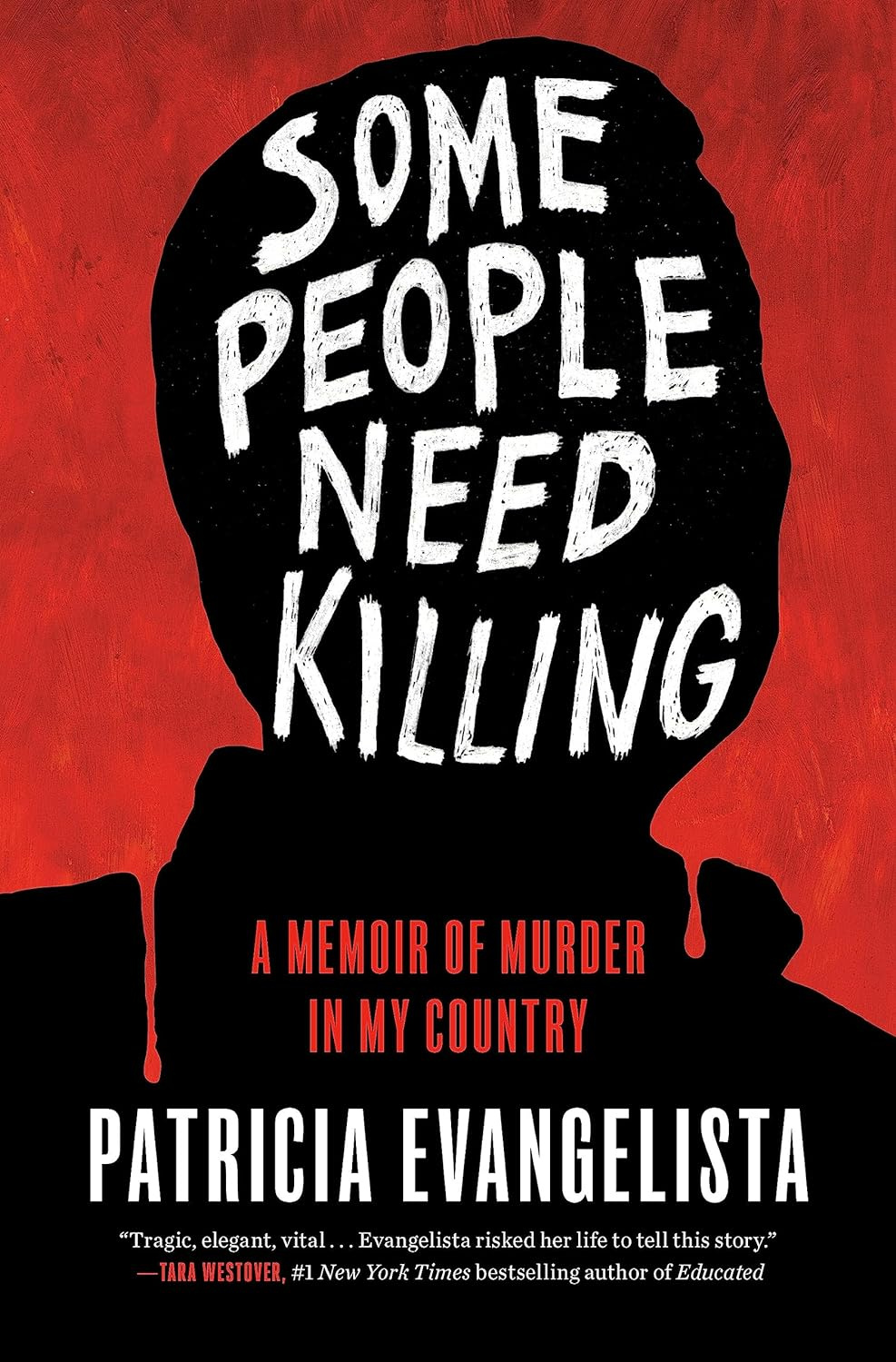

Before reading “Some People Need Killing,” a powerful new book by the Philippine journalist Patricia Evangelista, I had assumed that the definition of “salvage” was straightforward. The word comes from salvare, Latin for “to save.” You salvage cargo from a wreckage; you salvage mementos from a fire.

But the word “salvage” has another meaning in Philippine English. This definition derives from salvaje, Spanish for “wild.” The calls it a “complete semantic change from the original English meaning ‘to rescue.’” It is a contronym: a word that can also mean its opposite. “To salvage” in the Philippines means “to apprehend and execute (a suspected criminal) without trial.”

Evangelista calls this a corruption of the language — one that turns out to be horrifically apropos. “Some People Need Killing” mostly covers the years between 2016 and 2022, when Rodrigo Duterte was president of the Philippines and pursued of “salvagings,” or — EJKs for short. Such killings became so frequent that journalists like Evangelista, then a reporter for the independent news site Rappler, kept folders on their computers that were organized not by date but by hour of death.

The book gets its title from one of Evangelista’s sources, a Duterte-supporting vigilante called Simon. “I’m not really a bad guy,” Simon told her, explaining that he was making the slum where he lived safer for his children. “I’m not all bad. Some people need killing.” They don’t just deserve it; they require it. Responsibility for the deaths rests with the dead themselves. “The language does not allow for accountability,” Evangelista writes. “The execution of their deaths becomes a performance of duty.”

Evangelista was born in 1985, a few months before the Marcos dictatorship ended and a new era of Philippine democracy began. She was a young public-speaking champion who became a production assistant at an English-language news channel and a columnist for one of the daily papers, before switching focus to investigative journalism. It was the disappearance of two young women in 2006 that dispelled her illusions about her government. The women were community organizers. Eventually, sworn testimonies and commissions pieced together the truth. The women did not simply “disappear”; they were disappeared. They had been abducted and tortured by the military.

This was a decade before Duterte ascended to the country’s highest office. The book is mainly about him, but Evangelista wants us to know that Duterte did not come out of nowhere. Before his landslide victory in the presidential election of 2016, he was the longtime mayor of Davao City on the southern island of Mindanao. He pretended to come from humble beginnings when in fact he was a scion of the elite.

In the late 1980s, anti-communist vigilante groups were endorsed by President Corazon Aquino, whose People Power Revolution had peacefully toppled the Marcos dictatorship. As the communist presence ebbed in Davao City, counterinsurgency methods were used to target criminals and suspected drug users. When Duterte became mayor in 1988, bodies started showing up with notes reading “Davao Death Squad.”

Duterte categorically denied the existence of the death squads one moment and denied it a little bit less the next. Sometimes he loudly declared that he would kill people. “If you are doing an illegal activity in my city,” Duterte announced to reporters in 2009, “you are a legitimate target of assassination.” Pledging to kill Filipinos became part of his platform. “Am I the death squad?” he said in 2015. “True. That is true.”

Duterte’s supporters expressed a similar kind of identification. “Where I come from,” one told Evangelista, “most people were Duterte.” Evangelista notes the total devotion conveyed by the absence of a preposition. Duterte was elected because his profanity and threats apparently meant different things to different people. One supporter believed that the people Duterte promised to kill were the sort of people who should be killed. Another insisted that Duterte was just kidding, saying whatever he needed to say to appeal to the masses. He assembled an odd coalition among those who took him at his word and those who didn’t. “To believe in Rodrigo Duterte,” Evangelista writes, “you had to believe he was a killer, or that he was joking when he said he was a killer.”

The book is divided into three parts: “Memory,” “Carnage” and “Requiem.” “Carnage” describes how Duterte made good on his promises that Filipinos would die. The Philippine National Police put the number of casualties at about ; Evangelista says that the real total is likely much higher, though even the highest estimate, of more than 30,000 dead, fails to capture the brutality of Duterte’s war.

She recounts a few killings in heart-rending detail. A 52-year-old mother and her 25-year-old son were killed by their policeman neighbor over an improvised firecracker on their own lawn. Evangelista saw the 11-second video clip filmed by a 16-year-old relative of the victims. Until then, she had been piecing together murder scenes from a hodgepodge of police reports, testimonies from frightened witnesses and grainy CCTV footage.

“There should have been an explosion, a mushroom cloud, something, somewhere, signaling the sudden turn from life to death,” she writes, surprised at how the “tinny smack” of the gunshots sounded so quick and banal. For years, she had been writing about death, and she is startled to realize a chilling truth: “It takes longer to type a sentence than it does to kill a man.”

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE