WASHINGTON >> A showdown with Congress that has the nation’s creditworthiness at stake; a frenzied scene at the border as pandemic restrictions ease; a pivotal foreign trip meant to sustain support for Ukraine and contain a more assertive China in the Indo-Pacific.

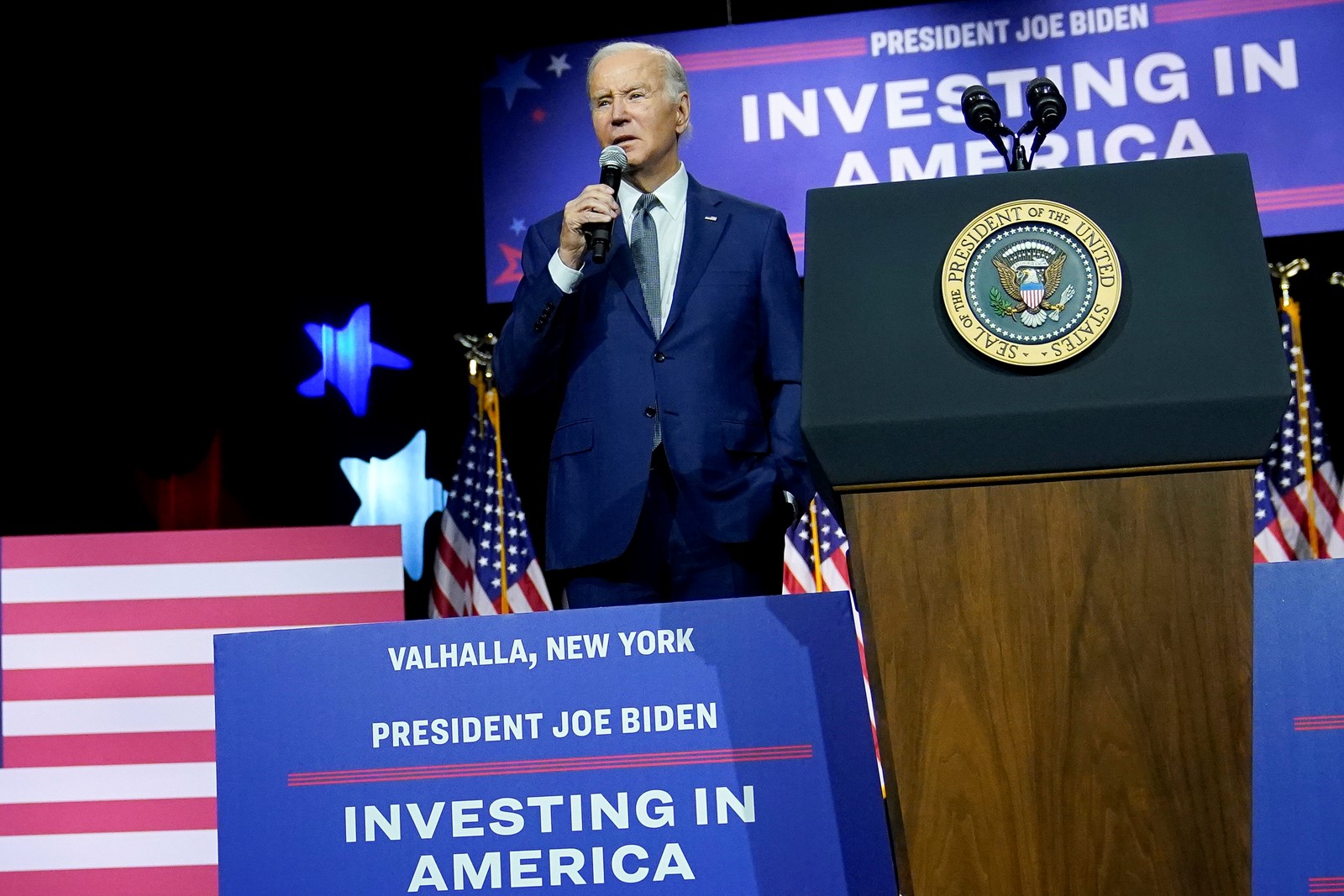

Three weeks since launching his reelection campaign, President Joe Biden is confronting a sweeping set of problems in his day job that defy easy solutions and are not entirely within his control. If, as his advisers believe, the single best thing Biden can do for his reelection prospects is to govern well, then the coming weeks can pose a near-existential test of his path to a second term.

Economists warn that the country faces a debilitating recession — and worse — if Biden and lawmakers can’t agree on a path to raising the debt limit. Biden wants Congress to raise it without precondition, equating Republicans’ demands for spending cuts with ransom for the country’s full faith and credit.

The expiration of the COVID-19 public health emergency meant the end of special pandemic restrictions on migrant procedures on an already taxed U.S.-Mexican border. His administration has responded with new policies to crack down on illegal crossings while opening legal pathways encouraging would-be migrants to stay put and apply online to come to the U.S. But Biden himself has predicted a “chaotic” situation as the new procedures take effect.

These tests comes as Biden prepares to depart Washington on Wednesday for an eight-day trip to Japan, Papua New Guinea and Australia. Biden will try to marshal unity among Group of Seven leading democratic economies to maintain support for Ukraine as it prepares to launch a counteroffensive against Russia’s invasion, and to invigorate alliances in the face of China’s forceful regional moves.

Biden put his ability to solve problems at the core of his pitch to voters in 2020 and it is central to his argument for why, at 80, he’s best prepared for four more years in the White House.

“I’m more experienced than anybody that’s ever run for the office,” Biden told MSNBC this month. “And I think I’ve proven myself to be honorable as well as also effective.”

Yet the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 undercut Biden’s image as an effective manager, sending his approval ratings sharply down, and he’s still working to recover.

An April poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found Biden’s job approval rating at 42%, a slight improvement from 38% in March. The March poll came after a pair of bank failures rattled an already shaky confidence in the nation’s financial systems, and Biden’s approval rating then was near the lowest point of his presidency. It also found that 26% of Americans overall want to see Biden run again — a slight recovery from the 22% who said that in January. Forty-seven percent of Democrats say they want him to run, also up slightly from only 37% who said that in January.

Aides note that Biden entered the White House when the country faced even greater trials: the COVID-19 pandemic, an associated economic crisis and strained international alliances after four years of Donald Trump’s presidency.

“President Biden continues to leverage his experience and judgment to fight for middle-class families and mainstream values, including by standing against congressional Republicans’ extreme MAGA threat to trigger a downturn” unless they get sweeping spending cuts, said White House spokesman Andrew Bates.

Biden said Saturday it’s “hard to tell” how staff-level talks to avert a crisis on the debt limit will shake out. He plans to reconvene with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy and other congressional leaders before he heads overseas, but the White House has been firm that though Biden is open to considering spending cuts as part of the budget process, he won’t agree to them as a condition for raising the debt limit.

“There’s no deal to be had on the debt ceiling,” White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Friday. “There’s no negotiation to be had on the debt ceiling. This is something that Congress needs to do.”

U.S. officials are warning that the impasse threatens national security. Pentagon brass already warned it could hurt pay and benefits for troops and U.S. standing worldwide, said National Security Council spokesman John Kirby.

“It sends a horrible message to nations like Russia and China, who would love nothing more than to be able to point at this and say, ‘See, the United States is not a reliable partner. The United States is not a stable leader of peace and security around the world,’ ” he said.

Biden also faces a key test at the southern border, where the transition away from Title 42 has been anything but simple. Migrants along the border still were wading into the Rio Grande to take their chances getting into the country, defying officials shouting for them to turn back. Lawsuits have threatened measures to release migrants into the U.S. to avoid overcrowding in border patrol facilities as well as efforts to crack down on asylum seekers entering the country.

But the problem can’t be solved by the U.S. on its own.

The U.S. increasingly has seen migrants arrive at its Southern border who are from China, Ukraine, Haiti, Russia and other nations far from Latin America, and who are increasingly family groups and children traveling alone. Thirty years ago, by contrast, illegal crossings were almost always single adults from Mexico who easily were returned back over the border.

Meanwhile, Border Patrol agents are encountering more nearly 8,000 migrants per day, and the human toll of the challenge was driven home in recent days by the death of a 17-year-old boy in U.S. custody. An investigation continues.

“A decision from one single country is not going to fix the challenges,” said Olga Sarrado, a spokeswoman for the U.N. refugee agency.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE