At first, the business of death keeps you spinning.

There’s the funeral: Burial instructions. Flowers. Luncheon. Photo boards. Thank you cards. Hours and hours of talking, explaining, comforting, being comforted.

There are notifications: Banks. Social Security. Pension distributors. Ancillary medical help.

Then there’s all that sorting: Photos. Keys. Coins. Keepsake jewelry. Envelopes of Teamsters’ good driving rewards. Christmas cards. Sweatshirts. Mobility devices. Cleaning supplies. A pile of sentimental cards more than 12 years old, all of them with hand-written love notes from your mother, his wife of 56 years — “Happy Birthday, Vince. I hope you have the best year ever. Love, Ruth.”

When the work has settled, and the shock has calmed, leaving you alone with the loss, that’s when the racing thoughts begin to consume you — where is he now, can he hear you, is he OK, is he alone, is he in need?

And then one night, the tables turn and you awaken — your heart racing, your eyes damp — with a single realization:

You are an orphan.

Both of your parents are gone. Dust. Memories. The past.

Now what?

You are a car without an engine, an assignment without instructions, a clock without hands. You are suffocating even as you breathe deeply.

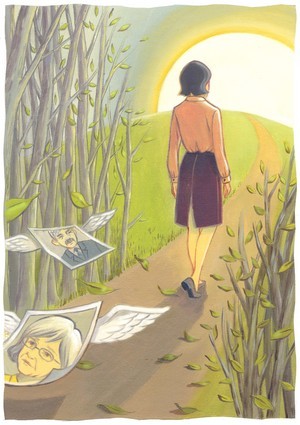

You see yourself in motion completing tasks, doing as expected, but without definition. A blob without parameters. No hands on the steering wheel and no one watching as you careen across the lanes.

The word orphan conjures up images of small, fragile children, left alone and vulnerable in a big, uncaring world. Even though you are hardly a child, the vulnerability seems immense. Even though you no longer need your parents’ guidance or money or take on things, even though you have certainly made it safely to adulthood, you are adrift, untethered.

Oh, you tell yourself you should be happy, that they are now at last together, reunited in wherever it is humans go after death.

But you are still here. Without them. No mother. No father. No spine. No footings. No foundation. No smile of approval. No raised eyebrows of disappointment. No “it’ll be OK” summations. No anything.

Of course, you no longer needed parents as they are defined by Webster’s. You’re all grown up. You have been making your own decisions, choices, money, meals, relationships and way through life for decades.

In fact, in recent years, they were more dependent on you than you had been on them.

But they had been a fixture, a comfort, an easy chair, a friend. And the void is tremendous.

You didn’t always agree on politics, movies, choice of vehicles or what to serve on Christmas Eve, but, despite your differences, they were always on your side. And you on theirs.

Granted, relationships are challenging and yours wasn’t always smooth or easy. There were periods of tumult and deep disagreement.

There were definitely words said that probably shouldn’t have been — on both sides.

But the trust was a safety zone — a place where anything could be said, then rethought, reworked, re-presented and, if necessary, completely forgiven and forgotten.

My teen years were contentious as I sought a very different path from theirs. Often, during this time, it seemed we had very little in common.

But for many years after I’d reached adulthood, my parents were my contemporaries. My mother and I shared a love for reading, mysteries, plays and fashion. I took her to the theater, the Art Institute, and trendy restaurants. I often took her on vacation with us. She was my go-to for planning holiday outings or meals.

After she passed, my father and I shared more logistical missions. I drove him to the grocery store and the hospital when he needed surgery. I took him to the Bridgeview Courthouse during the COVID shutdown because he needed a copy of his birth certificate. And countless times I accompanied him to Huck Finn Restaurant because he loved the “Becky Thatcher Breakfast.”

Of course, most recently, I was his caregiver, doing my best to keep up with so many different duties. He was not happy about needing me, about losing his independence, but he always seemed happy to see me. He’d comment on the news, maybe because his life had become reduced to what happened on his television set, or perhaps because he thought that was our common bond.

The past decade brought role reversals. So many times, I was the one making doctor appointments, delivering meals, buying groceries, vacuuming rugs, changing sheets. I was the one making calls on his behalf, looking up things “on that computer” and then explaining instructions. I was sorting his meds and holding his hand when things got bumpy or scary.

Three times in the past few years, he called me in crisis and, because he refused an ambulance, I frantically drove the 40 minutes to his home so I could then drive frantically to the emergency room. Later, after he moved into assisted living, we became frequent flyers at Palos Hospital, him groaning in despair at each new diagnosis, me fearing each time might mean the end.

For many years, he was the likeness of a child and I, the definition of a parent. Which perhaps is why I now feel as if I have lost both.

He died this past spring and each day since I have been standing on sand, feeling sure-footed one minute and about to topple over the next.

There is sorrow, panic, a gaping hole in my center. I am amorphic, a house on stilts during high tide, no longer bookcased by my past, no longer directed in my future.

There is only now — uncharted territory.

Is it selfish to feel sorry for myself?

Of course, I understand that both are “better off,” in the sense that they are no longer plagued by painful, soul-sucking illnesses. Of course, I am grateful that they are no longer suffering. And, of course I know, intellectually, that I will endure.

But every day I realize they are missed as they were loved: deeply, completely, unconditionally and eternally.

Donna Vickroy is an award-winning reporter, editor and columnist who worked for the Daily Southtown for 38 years.

donnavickroy4 @gmail.com

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE