In 1951, Woody Guthrie’s publisher gave him a newfangled piece of equipment: a Revere T-100 Crescent home tape recorder. It was primitive: mono and running at a noisy, lo-fi, 3 3/4 inches of tape per second, with a little mono microphone. Yet it allowed Guthrie to record his songs without visiting a studio, without recording engineers or time pressures, while he was at home in Beach Haven, a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, keeping an eye on three young children.

On Aug. 14, Guthrie’s estate will release “Woody at Home, Vol. 1 and 2.” It collects 20 songs and two spoken-word interludes, including a version of “This Land Is Your Land” that adds extra verses, as well as 13 newly unveiled songs. Guthrie’s own version of “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” — a song that became a folk-revival standard with a new melody by Martin Hoffman but that Guthrie had only recorded at home — was released Monday, his birthday.

Guthrie is revered nowadays as a model for singer-songwriters: plainspoken, casually tuneful, pointedly topical or slyly humorous. As a storyteller, he was able to compress narratives into terse rhymes while he empathized with an extraordinary range of narrators. And he was hugely prolific: He wrote lyrics for more than 3,000 songs.

“Woody represents the American spirit in such a noble and fierce way,” said historian Douglas Brinkley, who is working with the Guthrie family on a collection of lyrics. “You learn to live and love and work, to fight to have a democratic society and to never feel you’re too highfalutin, or that your money makes you better than somebody else. We’re just discovering this tape and some of these lyrics, but they still have zest to them — and they matter.”

Guthrie’s daughter Nora, a lifelong advocate and guardian of her father’s work, said, “In looking through 3,000 lyrics, only a handful are about his personal life.” She spoke via video from the offices of Woody Guthrie Publications in Mount Kisco, New York; Anna Canoni, her daughter, is the company’s president. “He uses ‘I’ all the time, but he’s an actor. I’ve never run into a songwriter that was able to put himself into so many different characters.”

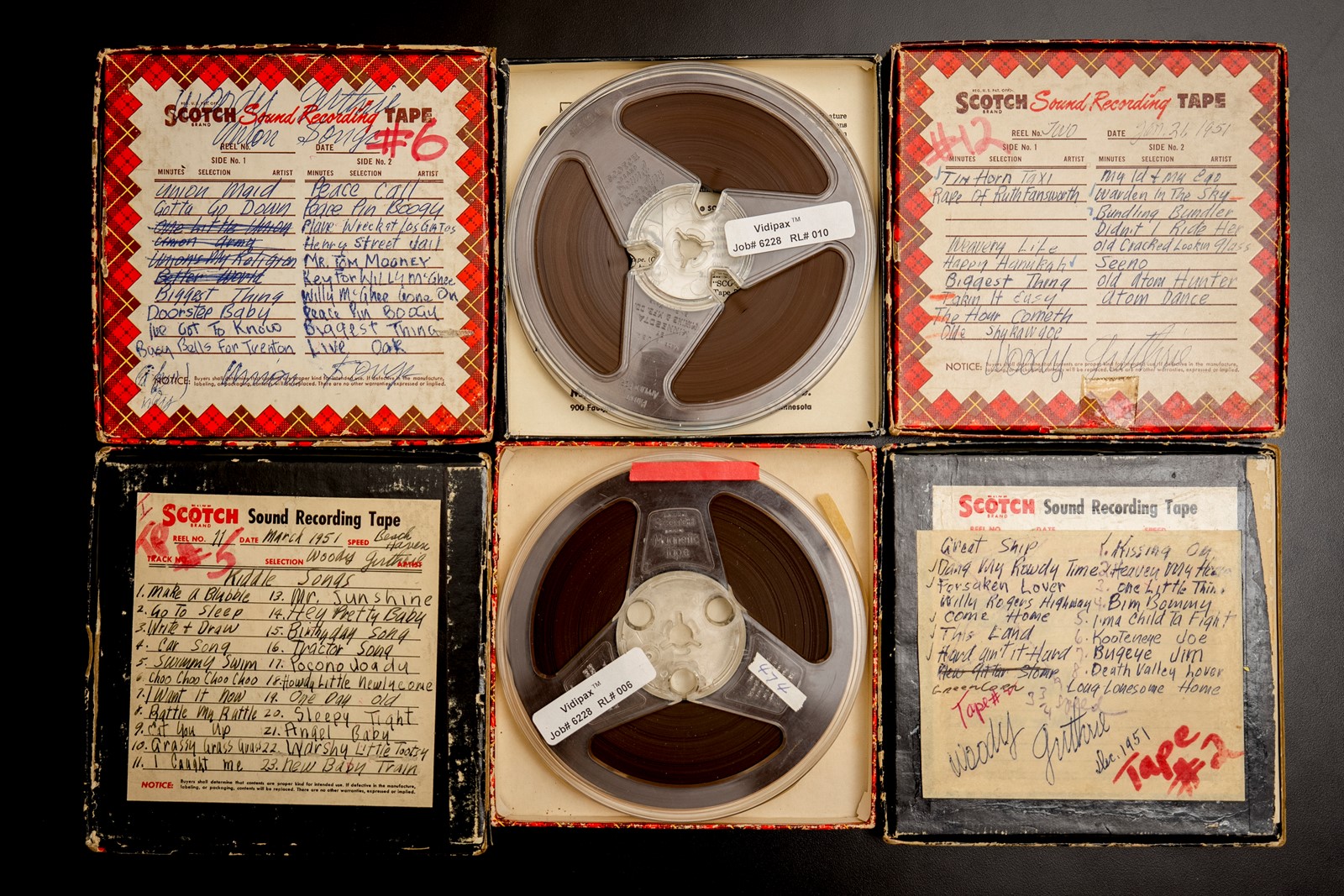

In the 1950s, Guthrie didn’t have a label that wanted to release his recordings. His publisher, Howie Richmond of TRO Music, urged Guthrie to sketch out new songs that could be pitched to other performers or printed as sheet music — and with the new recorder, he did. In 1951 and 1952, he filled 32 reel-to-reel tapes with songs and conversational messages.

“Woody was someone that loved to be the first at something,” said Canoni, who oversaw the new album. “It was a brand-new invention that had just come out, so he was absolutely fascinated with it. And he had a curiosity to share as much music as possible.”

As it turned out, the tapes would be Guthrie’s last recordings before he was debilitated by Huntington’s chorea. Until his death in 1967, he spent much of his later life in hospitals. The publishing company, now TRO Essex Music Group, kept the tapes through the decades, stored in good condition. But until recently, the Guthrie estate felt the music was too poorly recorded for public release.

“Since there was only one microphone, there was a real problem with the balance between Woody’s guitar and Woody’s vocal,” said Steve Rosenthal, who produced the album. Guthrie is credited as the original recording engineer.

Recently, audio software has arrived that can separate different instruments within a mono track. After trying many antique reel-to-reel tape machines, Rosenthal found a restored Ampex 350, originally built in 1950, that made the tapes sound best for playback to make digital copies. Software then separated Guthrie’s voice from his guitar; it also mistook a 60-Hz hum for a bass line and neatly separated that as well. From there, Rosenthal and mastering engineer Jessica Thompson rebalanced Guthrie’s voice and guitar, bringing them into vivid close-up.

Guthrie’s voice, with its Oklahoma drawl, is familiar from his studio recordings. But on the home recordings, it’s lower and warmer, not projecting for an audience or for studio technicians. “What I love about it is the gentleness of Woody’s voice — the quietness that exists, and the softness,” Canoni said. “I felt it was very powerful to hear, today, where the song emerges.”

The recordings include the sounds of children, cars, notebook pages being turned and guitar parts still being roughed out.

“Sometimes he’s trying to work through the arrangement as the tape is rolling,” Rosenthal said. “There are times where it feels like he’s not completely set in how he wants to sing it or what the guitar pattern is. And then after five or 10 or 20, 30 seconds, he starts to lock in to how he wants to present it. To be able to hear that process from Woody Guthrie is just amazing.”

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE