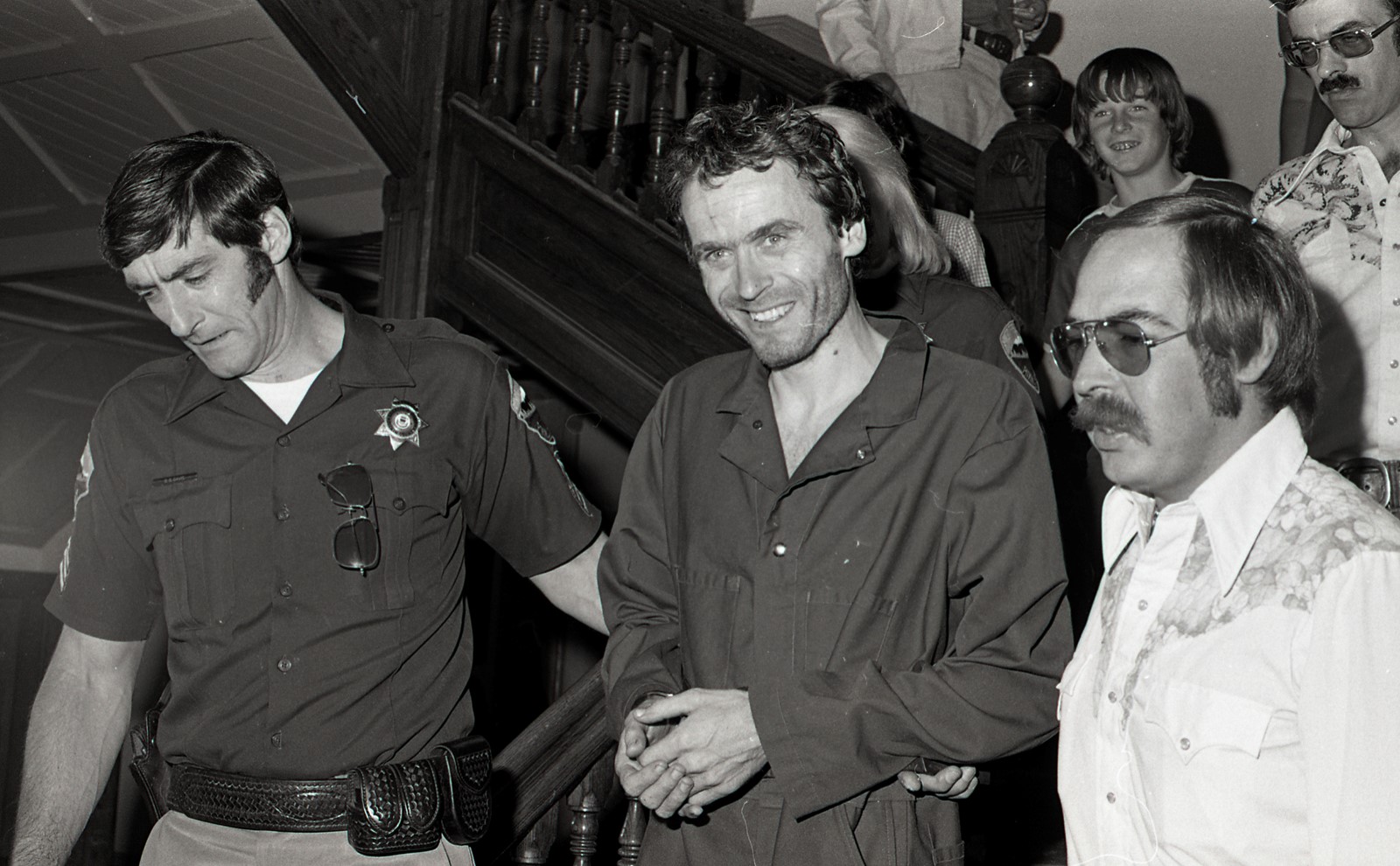

When notorious serial killer Ted Bundy leaped from a second-story window in Aspen’s courthouse and escaped into the Colorado high country in 1975, the Pitkin County sheriff immediately called up his posse to aid in the manhunt.

Area residents — some on horseback, armed with sidearms and clad in Stetsons — joined with sheriff’s deputies and other law enforcement officers to block roads, search cars and go door to door to hunt for Bundy, then suspected in the murders of eight women. Bundy broke into a cabin just south of Aspen as the June manhunt swelled to a 150-person effort. He pillaged supplies and tried to cut across to U.S. 50 but was thwarted by the spring snowpack.

Bundy turned back to the mountain cabin but found posse members staking it out. He retreated and stole a car. Around 2 a.m. June 13, Bundy was headed toward Interstate 70 in that stolen car — but was so exhausted that he weaved across lanes. He was pulled over for suspected drunken driving and arrested after a week on the run.

The sheriff’s posse was credited with helping to thwart Bundy’s escape by blocking him from resting at the cabin. He might have been awake enough to drive unnoticed out of town had he been able to recuperate at the cabin first, observers speculated.

Although Bundy’s escapade occurred a half-century ago, sheriff’s posses — volunteers whom county sheriffs can call on for a variety of duties — are not a vestige of Colorado’s past. More than a third of sheriff’s offices across the state still maintain active posses, The Denver Post found by surveying all 64 of Colorado’s sheriffs.

Most sheriffs keep uncertified posses, with civilian volunteers performing duties such as search and rescue, traffic control, patrols, crowd control and crime scene security, The Post found.

A handful of Colorado posses also include reserve officers — state-certified, volunteer police officers with almost full police power — but more often, reserves are a separate unit.

There are no statewide standards for posse members; sheriffs set their own training regimen. Reserve officers, on the other hand, must complete at least 254 hours of training and be certified by the state’s Peace Office Standards and Training, or POST, board.

Some sheriffs have come to rely on posse members more in recent years as the number of reserve officers has declined steadily. Colorado counted 528 certified reserve officers in 2015; that number slid to 360 this year, a 32% drop over the past decade. In 2018, the POST board certified 149 new reserve officers. In 2024, it certified 19.

Leaders at sheriff’s offices across the state pointed to several factors behind the decline in reserve officers, including the extensive required training, increased costs, a general shift away from volunteering, and the end of qualified immunity, a legal defense that previously protected sheriff’s deputies from being sued in their individual capacities in most cases.

“What we found with our reserve (officers) was that life happened fast,” said Capt. Michael Yowell at the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office, which disbanded its reserve officer program in 2023. “And trying to live two lives, one as a law enforcement officer and one working at the bank, they just collided too much.”

The agency still keeps about a 15-member posse, he said, which doubles the manpower of its 15 deputies. The posse takes a supporting role and typically does not engage in direct law enforcement, Yowell said.

“We don’t put a gun on their hip and say, ‘Hey, come back me up,‘” Yowell said. “They are more of a, ‘Hey, we need that ATV, could you put it on a trailer and bring it to us?’ ”

The posse was double its size years ago, but interest has waned. Still, the posse members do provide an extra set of eyes when deputies are spread thin, Yowell said.

“It sure makes a cop feel better, when he is 60 miles from the nearest backup, to know that there is a guy there who can help him if anything — we hope that never happens, but they’re there if we need them,” he said.

Posses long predate the United States.

They are rooted in English traditions that date to the ninth century, particularly the notion that policing should be done by the community, for the community, said David Kopel, research director at the Independence Institute, a libertarian-leaning Denver think tank.

“Posses were important on the Western frontier, but they were quite pervasive and common in more settled areas in the east for many, many years,” Kopel said. “When people were moving to Colorado, starting with the Gold Rush in 1858, and they began using posses, they were not creating something new.”

Under common law and Colorado law, judges, coroners and sheriffs can all call up posses, he noted, although the power is today almost exclusively used by sheriffs. Technically, participating in a posse is a civic duty, like jury duty, that can be compelled for men over age 16, Kopel said.

“But we haven’t had anything where anyone has been forced to do it for quite a long time,” he said. In the modern era, posses largely have been used when sheriffs do not have enough deputies to handle a situation, be it a blizzard, wildfire, concert or football game.

“Instead of tying up a sworn deputy manning a roadblock out in the middle of nowhere, they’ll do that for us,” said Park County Sheriff Tom McGraw, who has about a dozen regularly active posse members, all of whom carry guns after going through training and qualifying on the range.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE