Texas and California are sibling rivals.

They shared a life together in New Spain and Mexico, became American at nearly the same time, grew quickly, and now lead the nation in population diversity and economic power. This kinship has created an inseverable bond.

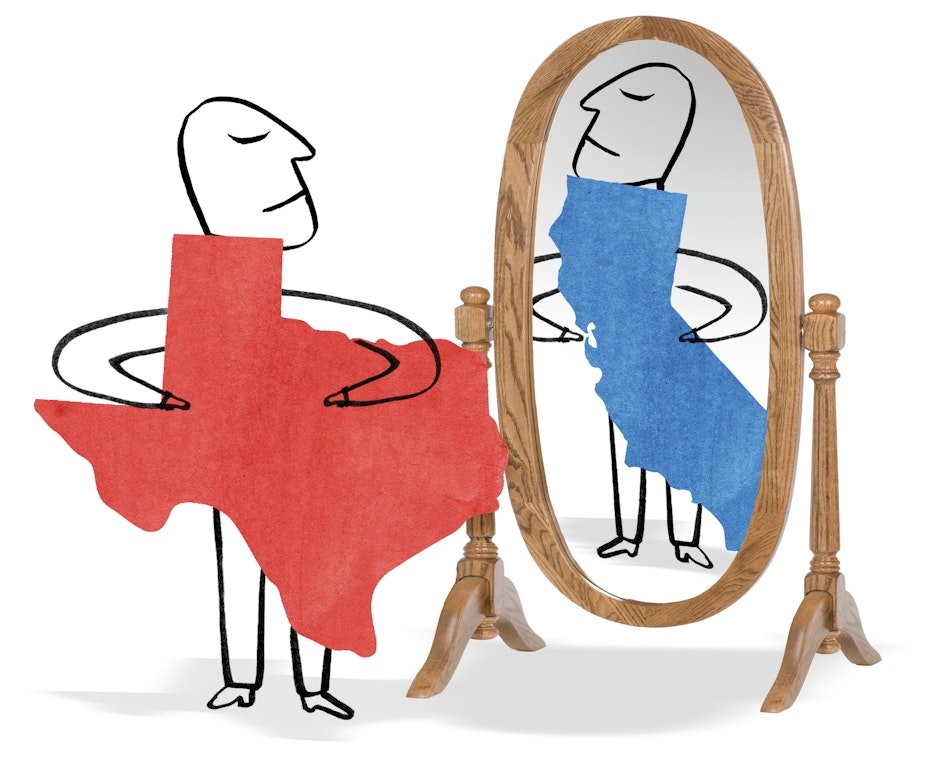

Author Lawrence Wright has expanded on the sibling metaphor by describing Texas and California as “mirror image twins.”

Mirror image twins are identical twins who separate relatively late in the gestational process. According to Wright as quoted in the Los Angeles Times, “The thing about mirror image twins is that if one is left-handed, the other will be right-handed. One will have a mole on the left cheek, and the other on the right cheek. In other words, they’re genetically identical, but they’re physically different. And I think there is something like that in the relationship between California and Texas. These two states, they intertwine like strands of DNA; they’re opposing each other, but they’re also related to each other, and they’re the poles around which our national politics tend to revolve.”

The twins’ opposing features have made them antagonists. As the national family has divided into competing and often hostile factions, its most powerful members have assumed leadership of the two sides. Partisan sorting has caused both states to become more ideologically distinct.

Texas has honed a conservative approach to nearly every policy question, while California has become consistently and emphatically progressive in its governance. To a large degree, both states have implemented their respective models at home, and both have fought to defend and advance these models beyond their borders.

One of the distinctive features of American federalism is that it reserves to the states a great deal of power to develop their own policies.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis authored perhaps the most famous endorsement of state policy pluralism in a 1932 case called New State Ice Company vs. Liebmann. The case challenged an Oklahoma law that defined the manufacture and sale of ice as a public utility and required ice-making businesses to obtain a license from the state.

Invoking the dominant judicial reasoning of the day, the court held that Oklahoma’s law violated a constitutional right — that is, one’s liberty under the 14th Amendment’s due process clause to engage in ordinary business without undue interference from the state.

Brandeis dissented, arguing that the Constitution does not forbid states from enacting economic regulations of this type. Brandeis extolled the value of experimentation.

“Man is weak and his judgment is at best fallible,” he wrote. “Yet the advances in the exact sciences and the achievements in invention remind us that the seemingly impossible sometimes happens....The discoveries in physical science, the triumphs in invention, attest the value of the process of trial and error. In large measure, these advances have been due to experimentation.”

Brandeis then turned to experimentation in public policy. “There must be power in the states and the nation to remold, through experimentation, our economic practices and institutions to meet changing social and economic needs,” he argued.

“To stay experimentation in things social and economic is a grave responsibility. Denial of the right to experiment may be fraught with serious consequences to the nation. It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

Brandeis’ opinion popularized the concept of states as “laboratories.” The term has been invoked countless times ever since by those who embrace a robust form of federalism, one that promotes the flow of innovations from the states and provides wide latitude for state-level policy diversity and trial and error.

The development in Texas and California of radically different policy models can thus be viewed in a Brandeisian way, that is, as a beneficial consequence of the nation’s constitutional design. A robust federalism allows Texas to operate a laboratory that generates conservative experiments, such as forgoing an income tax, rejecting Medicaid expansion and promoting an all-energy policy that includes full support for both fossil fuels and renewables.

At the same time, it allows California to pursue progressive experiments such as raising bountiful revenue through an income tax, expanding health care coverage by various means, and targeting carbon fuels for elimination.

The Texas model

The best argument for the Texas model during the first decades of this century was that a multitude of Americans voted for it with their feet. At the same time that California experienced a net-outmigration of more than 1 million residents, millions of Americans moved to the Lone Star State. Large numbers of middle- and working-class Americans concluded that it was easier to find a job, buy a home, support a family and build a future in Texas than in California or other blue states.

Texas’ emphasis on promoting growth and keeping costs low also made it a magnet for business relocation, formation and expansion.

The state’s light-touch regulatory system promoted economic development in numerous ways. In the energy field, the approach helped Texas reestablish its position as one of the world’s greatest producers. Partly through the state’s supportive regulatory policies, Texas exerted leadership in the shale revolution, which dramatically revived the nation’s oil and gas output, liberated the United States from its heavy reliance on foreign oil and generated wealth for the state and the nation.

At the same time, Texas encouraged, without aggressively mandating, the development of market-based green energy sources. Private industry responded by making Texas the national leader in production of wind energy and a rising contender in solar power. The economic benefits of Texas’ business-friendly, all-energy strategy spilled over into other sectors throughout the state.

The Texas model’s advantages also could be seen in housing. By placing comparatively few zoning or other restrictions on new home construction and by keeping labor and regulatory costs low, Texas expanded its housing stock to accommodate its fast-growing population. Despite rising demand for housing, this growth in supply allowed the state to keep median home prices below the national level and avoid the housing crisis that placed enormous strain on middle- and lower-income Californians.

From a fiscal standpoint, the Texas model was less highly leveraged than many blue states, primarily because Texans placed fewer demands on government. Compared with California and other blue states, Texas kept its spending low. It paid its public employees relatively low salaries, pensions and other benefits, and offered the poor modest social services, all choices that were defensible in light of the state’s comparatively low cost of living. These choices helped Texas keep its long-term spending commitments, and thus its fiscal vulnerability, below blue-state levels.

At the same time, the Texas model involved trade-offs and created its own vulnerabilities. Even in times of economic plenty, many believed that the state’s tight budgets created gaps in its education, health care and welfare systems, and allowed too many Texans to fall through a relatively thin safety net. Notably, not all such assessments came from the left.

Without embracing the progressive critique of the Texas model, some business-oriented conservatives argued that state’s tight fiscal policies caused the state to cut corners in areas essential to its future.

In 2016, Tom Luce, a prominent Dallas lawyer and former assistant secretary of education under President George W. Bush, founded Texas 2036, a business-backed organization with a mission to identify some of the greatest threats to Texas’ future and to seek solutions to those problems. At the time he founded the organization, Luce recognized that Texas faced a serious challenge educating a workforce for the 21st-century economy.

By 2036, he noted, the state’s much-expanded population would require millions of new jobs, many of which would demand high levels of education and specialized skills. For years, Texas had imported knowledge workers, including computer programmers, engineers and other highly educated employees, from other states and foreign countries. Luce and other business leaders argued that the state should do more to prepare its own residents for these types of high-end jobs.

Similarly, they contended that Texas should make more strategic investments in other areas, including infrastructure; health care access, affordability and outcomes; resource conservation and use; and modernization of government services. In short, powerful backers of the Texas model made the case that if that model is to succeed over the long run, it must adapt to the changing needs of a swiftly growing and diversifying society.

The California model

The best argument for the California model during these years was that the state maintained a flourishing economy while pursuing ambitious progressive goals. In the depths of the Great Recession of 2007–09, many concluded that California was a “failed state” because its economy was foundering and the capitol dome in Sacramento was submerged in red ink. In the decade that followed, however, the state staged a comeback.

The strength of the New Economy allowed California to shrug off the collapse of some of its older industries and the loss of residents and businesses to other states. In their place, California-based entrepreneurs birthed new enterprises and generated new sources of wealth. The world’s dominant technology cluster, centered in Silicon Valley, reinforced California’s position as a global leader in information technology, biotech, green energy, telecommunications, entertainment and related fields.

One could argue that California’s economy flourished not because of, but in spite of, the state’s high taxes and heavy regulations. In this view, California’s prosperity could be attributed to other factors, such as its favorable geography and climate, its entrepreneurial culture and a long history of investment in institutions such as the state’s world-class universities.

On the other hand, one also could argue that California’s progressive policies boosted the New Economy by helping its employers attract highly educated workers who embraced blue-state social and environmental values. The relationship between these workers and the blue-state model was mutually reinforcing. California’s Democratic coalition leveraged support from Silicon Valley, and California’s highly compensated residents were willing to pay a lion’s share of the state’s steep income taxes. During these years, they transferred enormous resources to the state treasury, thereby widening the state’s revenue advantage over Texas and other states

Between 2010 and 2020, as California’s revenue and spending grew in tandem with its booming economy, progressive Democrats across the nation used the Golden State as evidence for the proposition that a state (or the nation as a whole) could sustain economic growth while advancing a full-throttle progressive agenda.

During this period, California matched or exceeded red-state growth at the same time that it was taxing the rich, providing health care coverage to the poor, fighting climate change, expanding welfare programs, increasing pay and benefits to public employees and mandating a living wage, among other accomplishments.

But for Californians who had less education, fewer skills and, most important, lower incomes, the state was becoming a forbidding place to live. The rise of the New Economy corresponded with the collapse of the old one, as many sources of middle-class jobs moved to more business-friendly states or shuttered altogether.

California’s high costs for housing, utilities, gasoline and more made it hard for those who stayed to pay their bills. When housing costs were factored in, California had, by a substantial margin, the nation’s highest poverty rate, and the lack of affordable housing stock was at least partially responsible for the state’s shocking homeless crisis, with tens of thousands living in cars, on sidewalks and beneath bridges.

Finally, the experience of these years showed that the California model depends heavily on support from Washington, D.C., and thus is vulnerable to changes in federal policy. For example, during California’s budget emergency following the 2008 financial meltdown, the Obama administration and the Democratic Congress sent the state a lifeline in the form of large federal transfer payments funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, also known as the “stimulus package.” But there was no guarantee that other congresses and administrations would be willing to bail out the state every time its spending commitments exceeded its capacity to pay.

The stark transition from the Obama to Trump administrations made it clear to all that California, like Texas, has enormous stakes in the struggle for control of the federal government.

How to view the rivalry

What can we expect of these rivals and their competition?

In considering the future, we return to the fundamental question: Will the two states remain on opposite sides of the nation’s partisan divide? California presents the easier case. The Golden State has become one of the nation’s least likely places to change its partisan orientation, or even experience meaningful two-party competition. This is especially true as long as the Republican Party associates with Trumpism.

Barring some deeper national political realignment, California should remain solidly Democratic and ideologically progressive for a long time to come.

Texas again presents the more difficult and interesting question. The state’s rapidly changing demographics have given Democrats hope that they can turn Texas blue. However, Texas Democrats face a limiting factor. The state’s underlying political culture remains predominantly conservative, and its economic model aligns closely with the GOP.

A more likely scenario is for Texas to move into a period of two-party competition in which Democrats occasionally win elections, but Republicans remain largely in charge. This expectation is reinforced by the fact that Texas has become the essential cornerstone of the national Republican Party. The GOP will make maximum effort to defend its control of the state and, if lost, to reclaim it.

The models offer no easy synthesis — they necessarily require trade-offs and the setting of priorities. Nevertheless, especially in a time of disruption, some states may seek to break out of rigid left-right categories and consider creative alternatives for addressing complex policy challenges. These solutions may involve finding compromises between strong forms of the red- and blue-state models.

The Brandeisian model suggests that the federal system benefits from the presence of state-level policy differences. California Gov. Jerry Brown offered a defense of this view. The former Jesuit novice frequently extolled the virtues of “subsidiarity” — a principle of Catholic social thought that government choices should be made at the lowest level possible.

“There’s something called subsidiarity,” Brown said in an appearance on CNN in 2012. “And that is moving government responsibility to the institution closest to the people. And I think that’s a very important principle, consistent with fundamental human rights.”

A federal system committed to subsidiarity, state autonomy and policy pluralism could find much to celebrate in the rivals’ competing policy visions. As Lawrence Wright has observed, “The fact that the United States can contain such assertive contrary forces as Texas and California is a testament to our political dynamism.”

“But,” he added, “more and more I feel that America is being compelled to make a choice between the models these states embody.”

That is the challenge. As the red and blue state models have become more ambitious and more polarized, they also have become more incompatible and intolerant of difference. That is, they are forcing America to make choices.

The competing Texas and California approaches to energy and environmental policy offer an example. As part of its all-energy policy, Texas remains committed to developing its deep reserves of fossil fuels, while California wants to radically reduce the production and use of carbon-based energy. Unlike some preferences, these cannot easily coexist. California’s expensive efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions will be futile unless the rest of the country — indeed, the world — follows its lead. At the same time, one of Texas’ most important industries would be endangered if the nation fully adopted California’s aggressive climate policies.

The same can be said for many other policy areas in which the two models are diametrically opposed. Texas and California and their respective allies thus feel compelled to fight within the federal system to defend and advance their models and to defeat the other side.

An ultimate question

This circumstance raises an ultimate question. How should we think about our deepest political and policy differences? Many Americans lament our divisions and yearn for a time when the nation was more united. Their sense of longing is understandable. Our deep disagreements have worn on the national soul, and one can easily see how the country and its citizens would benefit from greater harmony and consensus.

Yet, in a free, pluralistic, democratic society, disputes over politics and policy are natural, even inevitable. Americans have always engaged in a clash of competing ideas and values; as the nation has diversified and its social consensus has weakened, disagreement has become even more inescapable. The challenge of living with difference has grown.

It is possible to view the nation’s differences in a more positive light and even to see them as a source of strength. To make that shift, it helps to realize that the United States would be diminished if all of its citizens were conservative or all were progressive, or if all of its states were like Texas or all were like California.

The national dialectic between right and left, red and blue, Texas and California, contributes to America’s remarkable vitality. It also helps to recall that Texas and California — and, more broadly, red and blue America — are more than rivals; they are siblings, members of a common family with a shared history and future.

If I remember that those on the other side of the partisan divide are members of my family, I can more easily become curious about their experiences, values and commitments. If I listen to them, they might be more likely to listen to me. I may never come to agree with them, but I can view them with less frustration, anger and fear. And, I am confident, we can learn from one another.

Again, one is reminded of an era of national division much deeper than our own. In an inaugural address delivered in the midst of the secession crisis, President Abraham Lincoln appealed to the states on the other side of the divide.

“We are not enemies, but friends,” he said. “We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection.”

One can hold the same hope today for Texas, California and the states in their respective camps. In our present era of polarization, these remarkable siblings have become rivals, but they need not be enemies.

Especially in light of the challenges the nation now faces, one hopes the rivals, and all of us, can compete for its future with great passion, but also with a spirit of mutual respect and, even, with affection.

Kenneth P. Miller is a government professor and director of the Rose Institute of State and Local Government at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, Calif. This column is an excerpt from his new book, “Texas vs. California: A History of Their Struggle for the Future of America.”