One of the more satisfying cheap thrills that comes with getting old is watching the discombobulated expression on someone young when they realize something they’ve dismissed as hopelessly parental is actually something rather . . . good.

Translation: Today’s sermon will be on Steely Dan and the vicissitudes of dad rock.

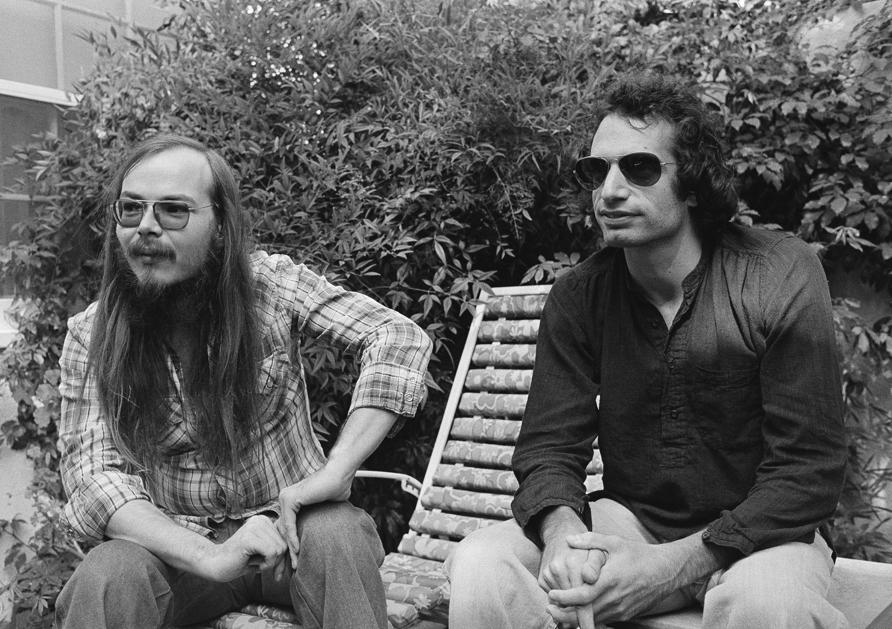

It’s prompted in part by a June 18 New York Times article in which writer Lindsay Zoladz admitted with a degree of chagrin that the music of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, long derided from her back-seat position on family car rides, has in her early 30s taken up permanent residence in her headphones.

Wrote Zoladz, “My recent embrace of Steely Dan has helped me settle into a newfound level of self-acceptance. I am a discerning, feminist-minded millennial woman. I also love dad rock.’’

Hold on a second. While this is a welcome development — and I appreciate that the Walter Becker estate responded to a tweet by Zoladz on the subject by tweeting back “We’ve been expecting you’’ — it reveals a fundamental misconception. Steely Dan isn’t dad rock. Never was. Steely Dan just pretended to be dad rock while playing a much longer and weirder game. That’s why the band was popular in the 1970s and why it continues to draw converts today.

But, first, a word about “dad rock,’’ a term coined (as the Times article points out) in a 2007 Pitchfork review of a Wilco album. The phrase is, of course, profoundly insulting while remaining absolutely undeniable, the end result of generations of boomers and Gen Xers treating the music of their youth as catechism for their children. Apostasy is guaranteed.

Dad rock takes its place next to dad jeans and dad jokes as an endearing diminution — you’re corny as hell, old man, but I guess we’ll keep you — but what kind of music actually qualifies? In practice, it’s whatever you play to your kids as important cultural education (disguised as fun) until they retaliate by going over to K-pop, Katy Perry, or industrial death metal. In theory, it’s all the classic rawk from your adolescence that you now hear in Starbucks and the aisles of Whole Foods. More damage has been done to Van Morrison’s career by the overplaying of “Moondance’’ than by his worst-charting album.

The Beatles don’t count as dad rock, because they’re foundational — a bouncy pop bedrock best introduced early. But the Stones, the Who, and (sob) the Kinks qualify. So does Springsteen, which I know is tough for a lot of you. So do the laid-back LA rockers of the 1970s — the Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, Warren Zevon, Jackson Browne — and Southern rockers like the Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and the Marshall Tucker Band. The prog rock that was so rad in 1974: Yes and ELP and all the rest? Don’t even try. My personal induction into the dad rock hall of shame came when a group of my guy friends and I started singing Jethro Tull’s album-long “Thick as a Brick’’ at a barbecue — and we knew every word.

I could go on; the point is that the process is a natural state of evolution. No growing person can develop their own taste until they overthrow their parents’ tastes, which means cherry-picking selected parental pop while making independent forays into their generation’s musical present and a self-curated past. Such rejection has gotta hurt, but it opens the floodgates for the tide to come the other way. My 20-something daughters send me their playlists now, and they’re fantastic. And you know who turns up on them a fair amount?

That’s right: tha Dan. The band gets held up as a pinnacle of dad rock by the sheer lite-FM smoothness of its sound, especially on the jazzier later releases. Coming over the PA system of a hotel lobby or a supermarket, songs like “Deacon Blues’’ or “Doctor Wu’’ sound deceptively inoffensive — the aural equivalent of whipped cream laced with Donald Fagen’s expressive sneer.

But while the Steely Dan oeuvre is easy to dismiss on a superficial listen, it becomes strangely dark and alluring once you start paying attention. The music is tightly thought out and arranged yet given to virtuosic solos that can take your breath away. The lyrics are opaque, funny, ironic, incredibly obscure. I listened to “Your Gold Teeth’’ (1973) for years wondering what the line “Even Cathy Berberian knows there’s one roulade she can’t sing’’ meant. Only with the rise of Wikipedia did I learn that Berberian was an avant-garde mezzo-soprano of the 1960s and a roulade is a coloratura passage of song.

One mistake some newbies make is thinking that Fagen actually means what he’s singing, as singer-songwriters are wont to do. But the Becker-Fagen catalog is studded with character songs, sung through the eyes of misfits and wannabes. The lyrics to one of their best tunes, “Any Major Dude Will Tell You’’ (from “Pretzel Logic,’’ 1974), sound like a parody of Me Decade mellow-speak. And guess what? They are.

(Side note: The connection seems hardly coincidental between this song and the Dude [Jeff Bridges] of the Coen brothers’ 1998 film classic, “The Big Lebowski.’’ What are Joel and Ethan Coen if not a celluloid version of Walter and Donald, with a shared interest in the twisted, the deadpan, and the exquisitely crafted?)

Steely Dan is, in other words, as subversive as you might expect from a band that named themselves after a dildo in a William S. Burroughs novel. The genuine oddity was that they were successful. Writes Mark Coleman about the group in “The Rolling Stone Record Guide,’’ “Rarely has pop music so complex actually been popular.’’

My own history with the band is neatly bracketed by early high school and late college and reflects the changing of a musical guard. I liked the hits off the first album, “Can’t Buy a Thrill’’ (1972), and while I bought the second album, “Countdown to Ecstasy’’ (1973) for “The Boston Rag’’ out of civic pride, I stayed for “Bodhisattva,’’ “My Old School,’’ and “King of the World.’’

The next two, “Pretzel Logic’’ and “Katy Lied’’ (1975), may be the best things the band ever did: Has there been a first-side run as fine as “Rikki’’ to “Night by Night’’ to “Any Major Dude’’ to “Barrytown’’ on “Pretzel Logic’’? Has there been a saxophone solo as intoxicating as Phil Woods’s work on “Doctor Wu’’ from “Katy Lied’’? But “The Royal Scam’’ (1976) felt cold and sterile — a real cocaine record — and by the time the band made their grand shift to sophisticated session-cat jazz fusion with “Aja’’ (1978), punk rock was coming in and I was turning up my nose at craft and prettiness for what seemed like — and often was — the honesty of frontal assault.

I hated that record when it came out. I hated “Aja’’ because it was meticulously clean, with no rough edges. Because it seemed immediately ready for the ski lodge and the shopping mall. Because it was hugely popular. Mostly, I hated it because it was so good.

It took me a few years, but I eventually caught up with the album. Fagen’s 1982 solo disc “The Nightfly,’’ possibly the man’s crowning achievement, helped with the reappraisal. (“Gaucho,’’ 1980 — meh.) What I find most interesting is how younger listeners like the Times’s Zoladz and my own grown children gravitate to both the band’s early pop hits and the sprawling majesty of “Deacon Blues,’’ “Peg,’’ and “Black Cow’’ — songs that to them are retro-kitschy-cool until they dig in and bliss out on a unique combination of exuberance and perfectionism, sardonic and swing. Regardless of when you first hear it, this is music to grow into on your own. Any major dad will tell you.

Ty Burr can be reached at ty.burr@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @tyburr.