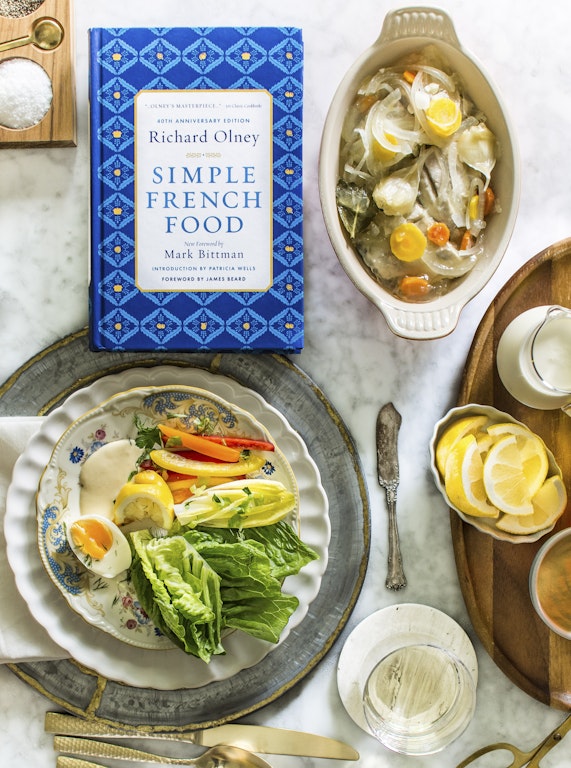

Simple French Food by Richard Olney, published in 1974, is a game-changer. One that Mark Bittman, a celebrated food journalist, says has a “lasting influence ... [that is] equal if not more important” than that of Julia Child or James Beard.

Olney, an American food editor and peer of widely recognized icons Beard and Child, is quite the legend in the culinary world. Though overshadowed by his contemporaries, Olney is praised for his depth of understanding the basics of good food and how to create it.

Whenever I’m asked what my favorite cookbooks are, my answer always includes the Time-Life series The Good Cook. Olney was the series consultant. The photos have detailed instructions on all kinds of techniques from preserving fruit to clarifying calves’ foot stock into gelatin. Many of the recipes in the back of each volume are from out-of-print books or needed translation. They were truly ahead of their time.

Once I learned of Olney, I began to research his work — and I was hooked. Here was a man who wasn’t a chef, yet he still appreciated and understood good food and told the world about it. I connected with him on this similarity, having no formal culinary training myself. I needed to know more.

The more I learned about him, the more I realized his palate, words and perspective significantly impacted the movement to eat local, fresh, simple ingredients — not only with home cooks, but also with chefs.

Olney was not a classically trained chef. He was a painter and journalist who loved good food and ultimately began to write on food and wine while living in France. He gained recognition for his expansive knowledge of French cooking, so much so that he became an editor and cookbook author. His work is scarcely known but widely praised.

His focus on culinary simplicity was against the norm in 1970s America. Bittman says this approach to food is of the utmost relevance to cooks today because Olney focused on that which transcends in all cuisine: “taking fresh, local, seasonal ingredients and treating them simply.”

Famed chef Alice Waters says that Olney’s Simple French Food is “one of her greatest sources of inspiration.” Her Berkeley, Calif., restaurant Chez Panisse, known for locally sourced ingredients, has changed the landscape of American restaurants since opening in the 1970s.

When I began cooking from Simple French Food, it was like meeting up with a friend who, while deep in thought, welcomed me along on his creative culinary wanderings. I fell right into step with what seems like a rattling of food instruction and thoughts. Some of the recipes presented are traditional in format, others are not. I found that, regardless of the presentation of instruction, it was worthwhile and educational.

Be warned, the title Simple French Food does not mean simple, easy recipes. Some instructions are long; some are not. However, this book will help you grow as a cook. Implement his motto on food (few, quality ingredients), and you will produce outstanding meals time and time again.

These are some of the key lessons I learned from the book:

Rebecca White of Plano blogs at apleasantlittlekitchen.com.

STUFFED BRAISED ONIONS

(OIGNONS FARCIS BRAISÉS)

4

large (5- to 6-ounce) sweet onions, peeled

2

tablespoons butter (divided use)

4

ounces lean bacon slices, rind removed, slivered crosswise

Handful finely chopped parsley

Handful finely crumbled stale bread, crusts removed

pound mushrooms chopped or passed through medium blade of Mouli-julienne

Salt, pepper, nutmeg

1

cup stock or bouillon

Heat oven to 375 F. Cut off about a quarter from the top of each onion and carefully empty it out, using a vegetable cutting spoon (melon-ball cutter) and leaving a double-walled thickness at the sides and an equivalent thickness at the bottom.

Chop the tops and insides finely, and stew them gently along with the slivered bacon in 1 tablespoon butter for 15 or 20 minutes, stirring regularly. The bacon should sweat, remaining limp, and the onions should be only soft and yellowed. Stir in the parsley and the breadcrumbs and remove from the heat a minute or so later.

Toss the chopped or julienned mushrooms in remaining 1 tablespoon butter, salted, over a high flame until their liquid is evaporated. Combine with the other mixture. Season to taste and gently, but firmly, pack the stuffing into the onion cases, mounding it with the hollow of a tablespoon.

Arrange them in a casserole or fairly deep oven dish just large enough to hold them, pour the stock into the bottom, bring to a boil on top of the stove, and cook, covered, in a 375 F to 400 F oven, basting regularly after the first quarter of an hour, for about 1 hour. The onion cases should be meltingly tender and, to be served out intact, a certain amount of care must be taken.

Makes 4 servings.

SOURCE: Simple French Food by Richard Olney

CHICKEN GRATIN (POULET AU GRATIN)

1

(2

Salt, pepper

2

tablespoons butter

1

large handful finely crumbled stale, but not dried, bread, crusts removed

cup white wine

cup heavy cream

3

egg yolks

3

ounces freshly grated Gruyère

Juice of

Heat oven to 400 F. Salt the chicken pieces and cook them in the butter over medium heat until nearly done and lightly colored on all sides — about 20 minutes, adding the breasts only after the first 10 minutes. Transfer them to a gratin dish of a size to just hold them, arranged side by side.

Cook the crumbs in the chicken’s cooking butter until slightly crisp and only slightly colored — still blond, stirring. Put them aside (don’t worry if a few remain in the pan) and deglaze the pan with the white wine, reducing it by about half.

Whisk together the cream, egg yolks, salt and pepper to taste, and cheese, then incorporate the lemon and the deglazing liquid. Spoon or pour this mixture evenly over the chicken pieces, sprinkle the surface with the breadcrumbs, and bake 20 to 25 minutes or until the surface is nicely colored and the custard is firm.

Makes 4 servings.

SOURCE: Simple French Food by Richard Olney

POTATO AND LEEK SOUP

(POTAGE AUX POIREAUX ET POMMES DE TERRES)

2

quarts boiling water

Salt

1

pound potatoes, peeled, quartered lengthwise, sliced

1

pound leeks, tough green parts removed, cleaned, finely sliced

3

tablespoons unsalted butter

Add the vegetables to the salted, boiling water and cook, covered, at a light boil until the potatoes begin to cook apart — or, until, when one is pressed against the side of the saucepan with a wooden spoon, it offers no resistance to crushing — about 30 to 40 minutes, depending on the potatoes. Add the butter at the moment of serving, after removal from the heat.

Makes 6 servings.

SOURCE: Simple French Food by Richard Olney