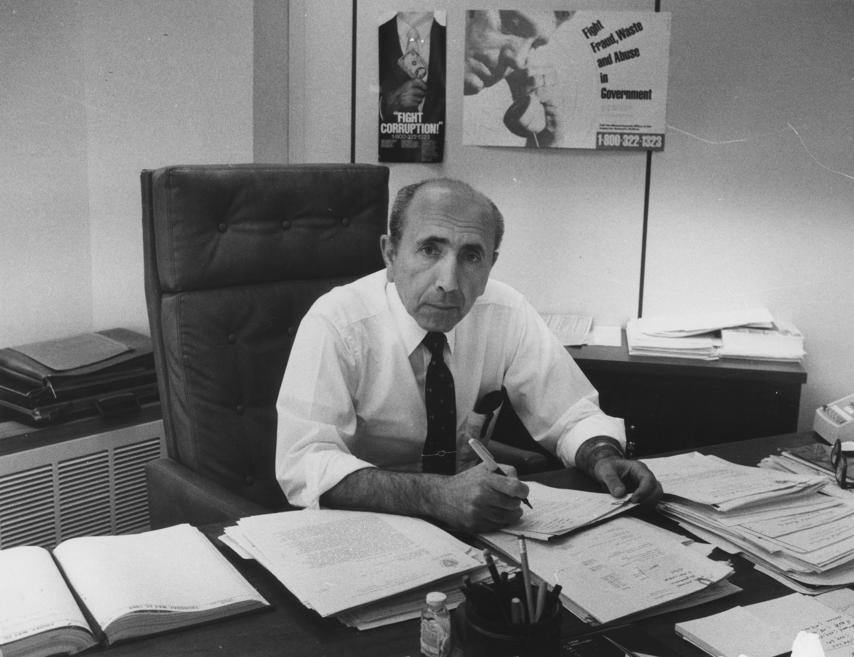

As the Commonwealth’s first inspector general, Joseph Barresi walked a precedent-setting political tightrope.

“When Barresi issues a critical management report or makes a referral to a law enforcement office, he is obviously going to make enemies,’’ Francis X. Bellotti, then the state attorney general, told the Globe in 1984. “When he finds no fault, he is castigated by those who have complained to him.’’

While serving consecutive five-year terms as state inspector general from 1981 to 1991, Mr. Barresi was responsible for detecting fraud, waste, and abuse in the expenditure of public funds. He was “the perfect fit for the job,’’ said Steve Cotton, his former first assistant.

“He was as meticulous as any accountant, as gifted a wordsmith as any editor, and as tenacious as a bulldog,’’ recalled Cotton, who added Mr. Barresi “set a high bar’’ for thoroughness and accuracy.

Mr. Barresi, who had served as executive director of the Boston Municipal Research Bureau from 1962 to 1975, died July 23 in his Cohasset home of complications from arrhythmia. He was 95.

The inspector general’s office was created after a Special Commission Concerning State and County Buildings — known as the Ward Commission, for its chairman, John William Ward — released a report highlighting rampant corruption in the awarding of state and county building projects.

During Mr. Barresi’s tenure, the inspector general’s office initiated investigations that resulted in numerous felony convictions. By monitoring projects, the office also prevented tens of millions of dollars in wasteful expenditures, according to the office’s annual reports.

Mr. Barresi was especially critical of the fiscal practices of the former Metropolitan District Commission, though his work also drew the ire of the state’s executive and legislative branches of government.

“I don’t think the inspector general’s office was set up to second-guess substantive decision making. It is supposed to ferret out corruption,’’ Frank Keefe, secretary of administration and finance under then-governor Michael S. Dukakis, told the Globe in 1985.

“At a minimum, this office is a deterrent,’’ Mr. Barresi responded then. “A lot of what this office has done is preemptive. I know we’ve made some people angry. It would be a hell of a lot less stressful around here if we hadn’t, but, hey, it goes with the territory.’’

Despite their occasional differences, Dukakis said after Mr. Barresi’s death that he “thought Joe was a damn good choice for inspector general. He set the parameters for that job and did it well, while caring deeply for integrity and honesty in state government.’’

One example was a lengthy investigation that uncovered no-show jobs for highway survey work in the state Department of Public Works. Twenty-one people were sentenced to prison terms or probation, a corporation entered a guilty plea, and $400,000 was repaid to the state, according to Cotton.

Another investigation revealed that some municipal treasurers were depositing funds in no-interest accounts in return for being wined and dined by banking institutions.

In 1989, Mr. Barresi issued a “code of conduct’’ and urged its adoption by public agencies and municipal officials to ban employees from accepting gifts and gratuities from private vendors. “This code is my advice,’’ he said at the time, adding that “public employees’ acceptance of gratuities from interested parties looks like, and is, a conflict of interest.’’

Mr. Barresi was also a driving force in the 1990 adoption of the state’s Uniform Procurement Act, which set down purchasing rules for all of the Commonwealth’s cities, towns, and other jurisdictions, including school districts and housing authorities.

Glenn Cunha, the current state inspector general, said Mr. Barresi had “a vision for the job and setting the groundwork,’’ and that his greatest contribution was the Uniform Procurement Act, “which we continue to enforce while training government officials responsible for spending our tax dollars.’’

A son of Rosario Barresi, a barber, and the former Antonina Pirri, Joseph Rosario Barresi grew up in South Boston and was a 1939 graduate of Boston Latin School.

Mr. Barresi was drafted into the Army in 1943. While serving in Japan, he was asked to take over running a golf course in Yokohama. He fell in love with the sport, playing golf until last year as a longtime member of Marshfield Country Club.

He graduated from Boston University with a bachelor’s degree in public communications and took graduate courses in public administration. Mr. Barresi was a member of BU’s National Alumni Council, a decades-long hockey season ticket holder, and for many years was the public address announcer at home football games.

After college, he joined the Boston Municipal Research Bureau.

“Joe’s experience here was the perfect background for his job as inspector general,’’ said Sam Tyler, the bureau’s executive director. “He learned the nuts and bolts of city government, was dogged in his research, and I considered him a man of integrity who devoted his life to public service.’’

Mr. Barresi, a retired Army Reserve colonel, formerly chaired the Cohasset Advisory Committee, and he was a past president of the Massachusetts Association of Town Finance Committees.

He was vice president for bonds at the Boston firm of Scudder Stevens & Clark when he read a newspaper advertisement for the new position of inspector general. He applied because he “missed the action’’ of public service. “I had been bitten by the bug. I enjoyed the jousting, the debating of issues,’’ Mr. Barresi told the Globe in 1981.

He got the job when the law to appoint the inspector general was changed from a unanimous vote to a majority from three officials — the governor, the state attorney general, and the state auditor. Then-governor Edward King voted against Mr. Barresi, but Bellotti and then-auditor John Finnegan voted for him.

“I’m going to be engaged in prevention,’’ he told the Globe in 1981. “You don’t wait for something to happen and then act.’’

Mr. Barresi was unanimously reappointed by Dukakis, Bellotti, and Finnegan, and was prevented by statute from serving a third term.

After leaving office, he was a senior fellow at the McCormack Institute at the University of Massachusetts Boston and an executive fellow and lecturer at what is now the Hoffman Center for Business Ethics at Bentley University.

“I can’t help but believe that through his office and through his code of conduct, Joe, whom I admired greatly, made the state a better place in terms of its ethical culture,’’ said the center’s founding director, W. Michael Hoffman.

Mr. Barresi met Velma Amistadi, a Trans World Airlines flight attendant, when both attended a TWA promotion in Boston. They married in 1959. Their late daughter, Gia, was a Globe All-Scholastic softball player at Cohasset High, and their son, Paul, an attorney who lives in Hanover, was a multi-sport athlete at Milton Academy.

A service has been held for Mr. Barresi, who in addition to his wife and son leaves a brother, Frank of Foxborough, and two grandchildren.

“I inherited my father’s love of sports and love of reading,’’ said Paul, who was once a spotter for his dad at BU football games, “and through his strong example, I have tried to be a reliable and honest person.’’

Marvin Pave can be reached at marvin.pave@rcn.com.