Traveling to Italy to be an “Artist in Residence’’ sounds a bit precious, as though one couldn’t possibly be an artist in residence in, say, Maine, where my wife and I live, but must travel to Italy in order to be one. But to Pat and me, as we flew away from Boston last June, it sounded like a potentially productive experience, and if it wasn’t, we could live with precious.

The Palazzo Rinaldi Artists’ Residency, in the tiny village of Noepoli (pronounced “No-a-po-lee’’ with the accent on the “a’’) is not easy to find, either on a map or in a car. But after the long drive from Rome down the A3, and after exercising my few words of Italian, mostly “Dove Noepoli?,’’ we found the small state road that leads to the village, passed through a tunnel, and the village appeared, spread out on a thin plateau high above like a fantasy of a medieval sanctuary.

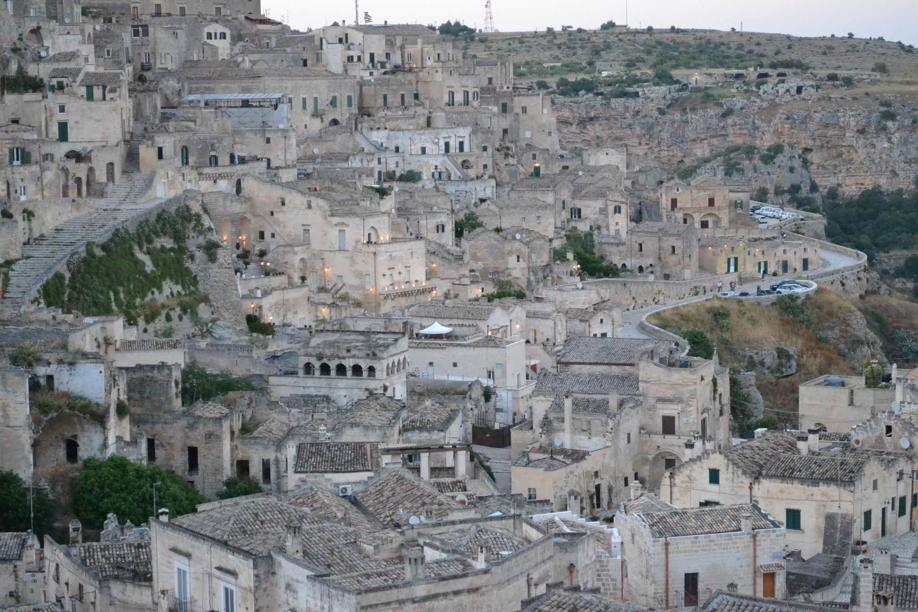

Noepoli is a dramatic village, occupying a narrow ridge called a calanchi (“badlands’’ in English) in southern Italy; they are the dominant landform here, as well as where most of the towns are located. You can be on the top of one calanchi and look out to a dozen other towns clinging to their own calanchi, each a speckled pattern of red and brown clay roof tiles.

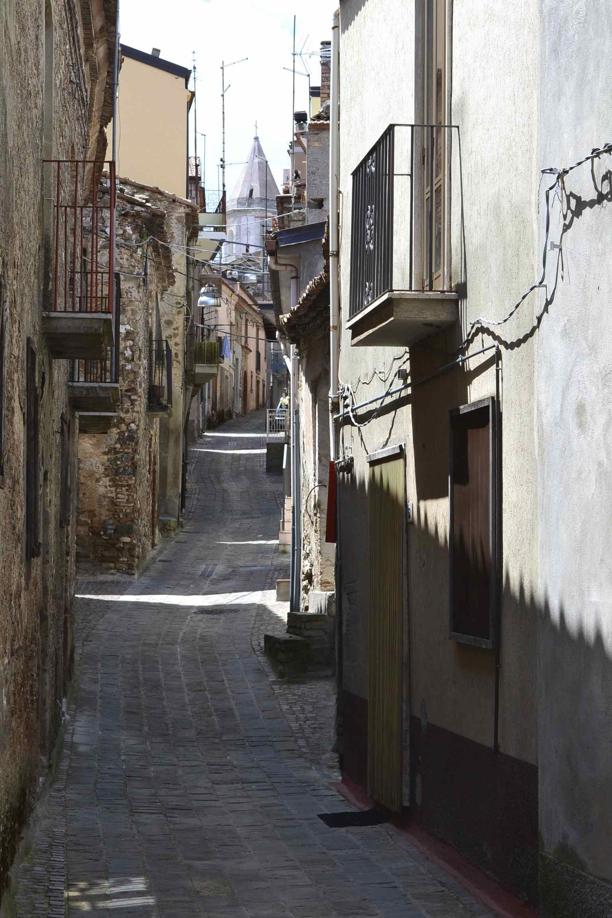

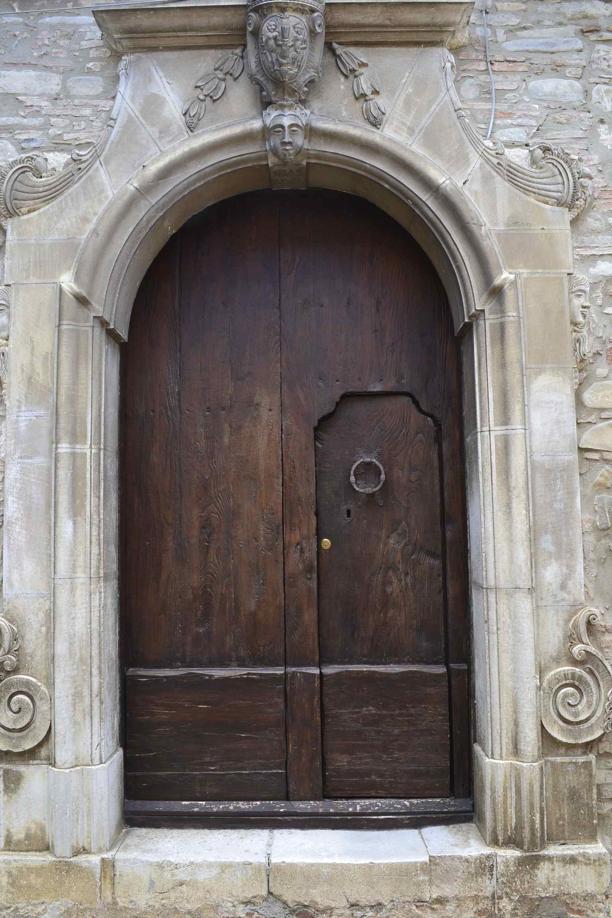

Once in the village, we drove around and around, lost, until we eventually found a way up to the very top of the village, to a flat, open space between the Catholic church on one side, the town hall on the other, and in the middle, facing south, a sweeping view of the hills and mountains and villages in Pollino National Park. The Park surrounds Noepoli and the other villages in this area. We walked down a narrow cobblestone alley to the old wooden door of #5 Via Rinaldi, and were greeted there by Raffaele and Pina, our wonderful Residency hosts.

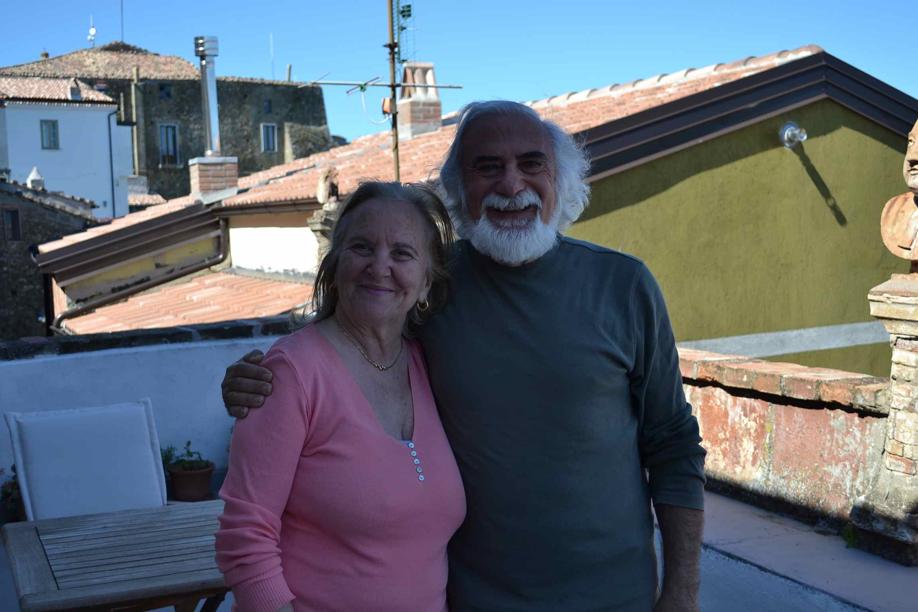

The Palazzo Rinaldi has been in Raffaele’s family since the early 1900s, long after the village was established (According to some sources, Noepoli dates from the 4th century BC). The Palazzo’s most beguiling feature is a terrace which runs along the front of the three rooms that make up the Residency. The terrace faces west and north, overlooking the valleys that temporarily interrupt the calanchi. The terrace draws one to it, to watch hawks soar on the currents, or to take a glass of wine out in the evenings and watch night drop.

One of the first things we noticed on arriving in Noepoli was a poster on a wall near the church, showing a young woman’s face. The few words I understood included “28 anni’’ or 28 years, and “triste’’ or sad. A few days later the funeral was held: The entire square between the church and the town hall was filled with people, overflowing from the church and listening to the service through the speakers that had been set up outside. Another day, when I was sitting on the terrace with Pina, the church bells began to ring; after several peals, Pina stiffened and said, “Oh, no, que triste.’’ I asked what was wrong. It seemed the bells were announcing the death of another elderly town resident. This is how news in this quiet, traditional village traveled: by church bell and bulletins pasted on town walls.

Every morning Pina and Raffaele set out a full breakfast on the terrace, including fresh fruits and vegetables, bought from the back of a farm cart that a farmer drove into the cobbled lanes in the morning. Once a week Raffaele would go to a nearby village, where a baker makes a traditional round, flat bread with a hole in the center. After breakfast, Pina would urge us to take slices of this bread, cut into triangles, along with some tomatoes, mozzarella and cucumber slices, which made for a fantastic lunch.

But the point of the Palazzo, of course, is to work on your craft, whether you are a painter (by far the most frequent type of resident), musician, or, like Pat and me, writers. Having put a busy spring semester at our colleges behind us, we were feeling a bit rusty as writers, but on the morning after our arrival we arranged spaces in our bedroom/study and settled down to it. I won’t claim any creative breakthroughs, but we did put in a full morning of writing every day we were there. We quickly discovered that the rhythms of Rinaldi fit us well: work in the morning until a late lunch, then excursions for the afternoon, followed by the search for dinner.

This area of Italy was made famous — perhaps infamous — by the painter and writer Carlo Levi’s 1947 book, “Christ Stopped at Eboli’’ (Eboli is a city to the north along the A3 to Rome), in which he told the story of the ignored, impoverished south, almost a Third World country within glamorous Italy. One expecting to find such a world now would be disappointed, if that’s the word. The towns in Basilicata can be a little worn, but many are in gorgeous settings, such as Terranova, an even smaller town than Noepoli about 12 miles away along a very twisty road, into the heart of the National Park. We went there because of the restaurant Luna Rossa, whose owner-chef, Federico Valicenti, is well-known both in and outside of Italy. Federico himself came out to take our order on the veranda. A round and cheerful ball of a man, no doubt he visited his attentions on us since we were the only ones attempting to dine at the uncivilized hour of 7:45 p.m.

We tried to keep our afternoon travels within 90 minutes of the Palazzo, since we liked it so much. We visited Matera, the UNESCO World Heritage site about 70 miles away, famous for its cave homes which have undergone a unique form of gentrification: from impoverished hovels to luxury hotels in the same cave, in a generation. Another afternoon we took a hike up to an overlook within the National Park, gaining a dramatic view of the village from above, with other calanchi in the background. On another, we drove east to Policoro, a gritty town on the Ionian Sea, and the beaches there.

Noepoli is not blessed with many restaurants — actually, it has only one — but my favorite dinner was here, at Il Fosso (“the ditch,’’ roughly). Il Fosso is a short walk downhill from the Palazzo and set in a grove of trees, near the fountain that flows with spring water, the same water that serves the town. The menu wasn’t elaborate, but it was thoroughly typical for the region. We shared a salad mista and each had a hot bowl of pasta — mine with mushrooms, eggplant, and cheese. As in every place we ate in Basilicata, the wine was good and cheap (sometimes wonderful and still cheap). The bill for the entire meal came to 20 euros, about $23 at the time.

The combination of location, culture, and writing time was, for us, perfect. It clearly wasn’t the kind of experience that everyone might value, but it surprised us at how well it satisfied our ambitions. The experience was indeed precious, and resulted in at least one piece of writing while we were in Residence: this one.

Michael D. Burke can be reached at mdburke@colby .edu.