PARIS — The French jihadi network that groomed one of the Nov. 13 Paris attackers went on trial Monday, minus its most infamous member, a man killed in the Bataclan concert hall on a night of bloodshed that left 130 people dead in the French capital.

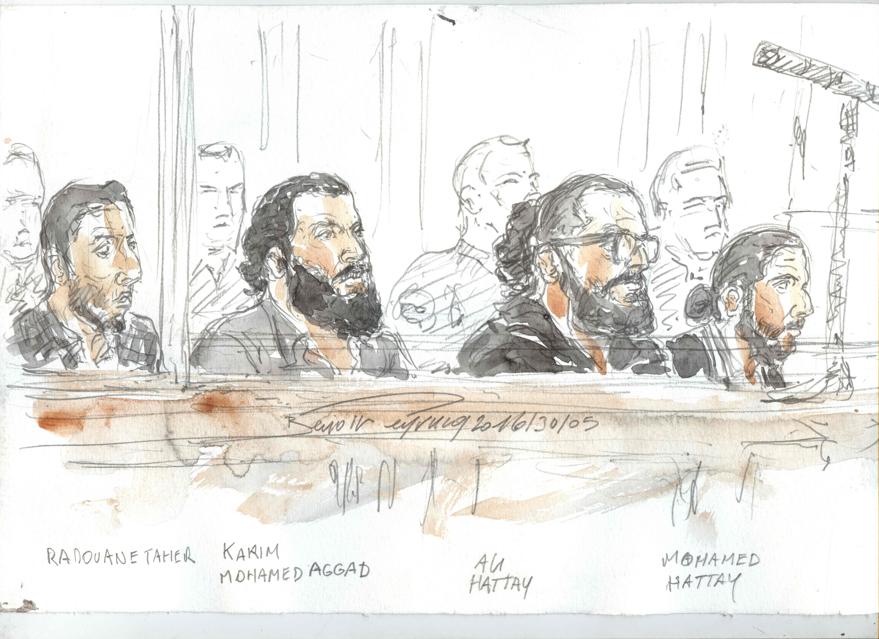

The seven defendants, friends from the eastern city of Strasbourg, were arrested in 2014 on suspicion of unspecified terrorist activity after returning from Syria. Court documents show no indication they were planning a specific attack at that time.

Two other members of the 10-person network died in Syria. And the final member of the Strasbourg group, Foued Mohamed-Aggad, remained at large and went on to participate in the Nov. 13 Paris attacks.

The defendants in Monday’s trial in Paris — who include Mohamed-Aggad’s brother Karim — insisted they had nothing to do with the Paris attacks.

The men insist they went to Syria for humanitarian reasons and were forced to join Islamic State as one thing after another went wrong with their journey. All returned to France by April 2014, telling investigators they were desperate to escape.

‘‘Humanitarian or jihadist?’’ the judge asked each man sharply. With different levels of equivocation, each man said they went to Syria with the intention of helping.

Karim Mohamed-Aggad asked that the defendants be judged for what they had done, and not for the deadly Nov. 13 attacks.

The group was recruited by Mourad Fares, who once boasted of grooming dozens of French citizens to join jihadists in Syria and who was arrested separately in late 2014 by French authorities. The Strasbourg men blamed their plight on Fares, who was not among those on trial Monday.

Fares did not meet the group at the border as they arrived in Syria, they told investigators — instead, they said they were picked up by members of the group later known as Islamic State and said they had little choice but to go along.

‘‘We were had by smooth talk. Islam was used to trap me like a wolf. When we arrived there, it was clear to me that the people there had nothing to do with Islam,’’ Karim Mohamed-Aggad told investigators, according to court documents.

He did not know, however, if his brother felt the same.

‘‘It is obvious that the shadow of Foued Mohamed-Aggad hangs over this case,’’ said Eric Lefebvre, lawyer for defendant Mohamed Hattay. ‘‘[But] what this man did, that’s his responsibility, his guilt, and it wouldn’t be fair today to tell these people today that they are partly responsible for what happened [on Nov. 13].’’

Six months after the November terror attacks in Paris, survivors and family members of those killed in coordinated attacks across the city met last week with the justices in charge of the ongoing investigation, seeking closure to the deadliest incident on French soil since 1945.

During a three-day hearing that began last Tuesday, more than 1,000 people touched by the attacks demanded specifics on how their loved ones died and how such a tragedy could have happened in Paris.

Most of those who died were shot as they watched a concert, others while they drank and chatted with friends at cafes.

The November bloodshed was ultimately claimed by the Islamic State, whose operatives largely planned their attacks from nearby Brussels. The same cell of terrorists then carried out the March 22 attacks on the Belgian capital’s international airport and metro system as authorities began to close in on their network.

‘‘The victims need direct contact with the judges,’’ said Juliette Méadel, the secretary of state responsible for victim support, in an interview.

‘‘They can pose many questions about the investigation and about what happened. The judges are the only ones who can speak precisely and who can verify details.’’