English spelling is notoriously a bear. Not a bare, of course, though bear and bare sound exactly the same. Due to the diversity of languages and typographical logistics that have influenced English, inconsistency is a constant in English spelling, a challenge that native speakers and those learning English as a second language bear alike.

As for anything wild, there have been numerous proposals to domesticate. Spelling reform movements have popped up since the 12th century. Past ideas range from modest (suggesting small, simplified changes in spelling) to radical (demanding brand new alphabets and/or phonetic spellings), resulting in a few changes here and there but not a lot to brag about.

Why is English spelling such a mess? The apparent mess is not due to a lack of rules, but an abundance of rules derived from English’s many influences. English spelling continues to change, but rarely due to top-down edicts: Spelling evolves when the masses make it happen.

David Crystal, author of “Spell It Out: The Curious, Enthralling and Extraordinary Story of English Spelling’’ and “Making a Point: the Persnickety Story of English Punctuation,’’ notes that the problem with English spelling is that we have only 26 letters in our alphabet — but more than 40 sounds in our language, which is primarily spoken, not written. That requires considerable creativity, which is facilitated and complicated by the many languages that influence English, not to mention typographical factors, like how a silent “e’’ used to be added to words by typesetters just to fill up space.

Silent letters have often been a target of reformers, but such letters usually emerged for a reason. Consider the word debt. In the logic of the 16th century, Crystal told me via e-mail, “the introduction of silent letters based on etymology was seen as the logical solution to the huge amount of variation in spelling found in Middle English.’’ He went on, “So, for example, with det, dette, deytt, and dozens of other variants around, it was logical to look to Latin for a standard form. For debt there was debitum, introducing the ‘b’ was a clear solution, especially as it would be pronounced in debit, etc. Similarly, the ‘b’ in doubt, the ‘p’ in receipt, the ‘l’ in salmon, and many more.’’

There are similar explanations for most spelling quirks, and many experts find the apparent unpredictability of English to be exaggerated. “One issue is that the quirky spellings can be so spectacularly quirky,’’ notes Anne Curzan, professor of English at the University of Michigan and regular contributor to the Lingua Franca blog. But, she adds,“more English spelling is predictable than unpredictable.’’

And when spellings don’t make sense, people start quietly changing them without much fanfare. Curzan notes examples such as donut replacing doughnut or lite for food products now. “I still tend to use catalogue, but the simplified catalog has become standard, too.’’

Along with such gradual simplifications, other spelling changes happen by way of error, such as eggcorns. Eggcorns, which have been discussed by lexicographers since 2003, are spelling errors that are logical, such as spelling free rein as free reign or chaise longue as chaise lounge. Sometimes the error makes so much sense and is so widely used that it becomes an accepted spelling.

Though many find eggcorns to be a mind-bottling (a misunderstanding of mind-boggling) phenomenon, they’re just part of spelling evolution. An older term for eggcorns and similar misunderstandings is folk etymology, a fitting name for changes that come from the people.

Probably the most successful push to change spelling as we know it was that of Noah Webster via his 1806 dictionary, “A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language.’’ Most notable, Curzan says, is “how many of [the Webster changes] stuck, including honor (not honour), theater (not theatre), defense (not defence), realize (not realise), and the like.’’

“It was a moderate reform, but motivated by the need to provide the new country with a new language,’’ Crystal notes. “It was the political power behind his proposals that enabled them to become institutionalized.’’

In fact, the people hold all the cards when it comes to spelling change, which is why spelling reform is nearly impossible: There’s no central spelling authority to mandate a change, for which we should probably be thankful.

“For all the complaining we may do, we often get quite attached to the look of words in their current spelling. We like having a visual distinction between eight and ate, through and threw,’’ Curzan said. “Dropping the silent endings off words can make them look incomplete (e.g., cigaret, imagin, hav). And it can be helpful for spelling to hold onto the etymological connection between words whose pronunciations have changed over time — for example, south and southern, where we spell the first vowel the same way even though now they are not pronounced the same way.’’

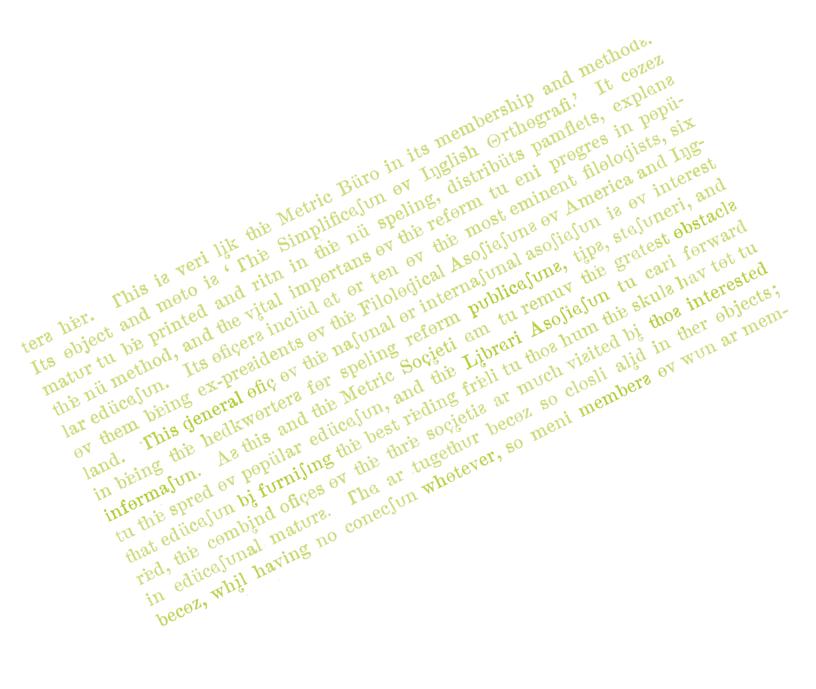

Two journalists, Gus Lubin and Skye Gould, recently made the case that, with texting and emojis running wild, now is the perfect time to improve and preserve English spelling. Writing for Tech Insider, Lubin and Gould suggested reviving spelling proposals of the 1906 Simplified Spelling Board, such as spelling heart as hart or scenery as senery. (A few decades before that, the Spelling Reform Association worked to make a world where their name would be the Speling Reform Asoshiashun.)

Yet if history is any guide, modern English spellings will evolve in due time — as spellers themselves dictate. Plus, as Curzan notes, if we started simply spelling words as they sound, what fun would spelling bees be?

Mark Peters is the author of the “Bull[expletive]: A Lexicon’’ from Three Rivers Press. Follow him on Twitter @wordlust.