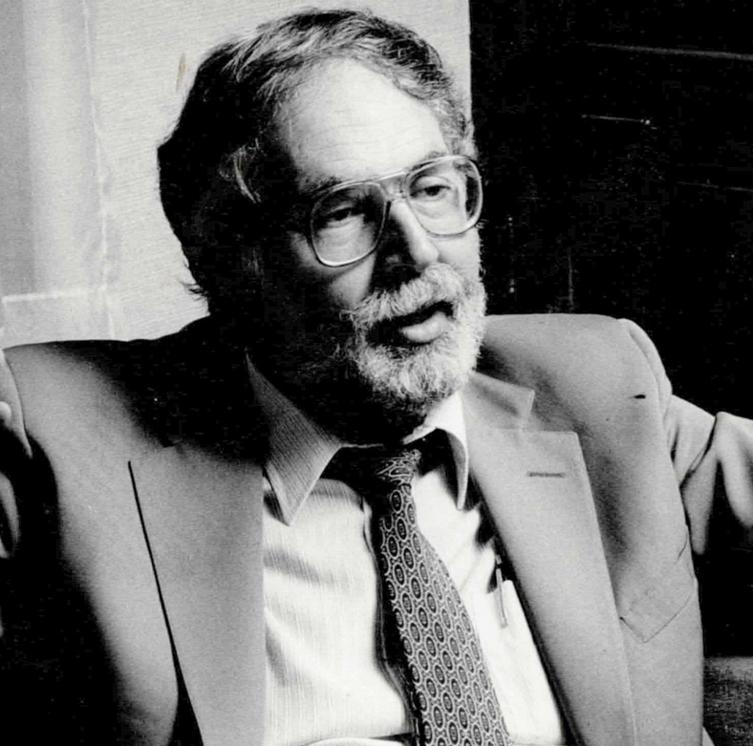

NEW YORK — Donald Jelinek, who quit a Wall Street law firm to defend civil rights workers in the South and later inmates accused in the Attica prison revolt and Native Americans who seized Alcatraz Island to dramatize their grievances against the government, died on June 24 at his home in Berkeley, Calif. He was 82.

The cause was lung disease, said his wife, Jane Scherr.

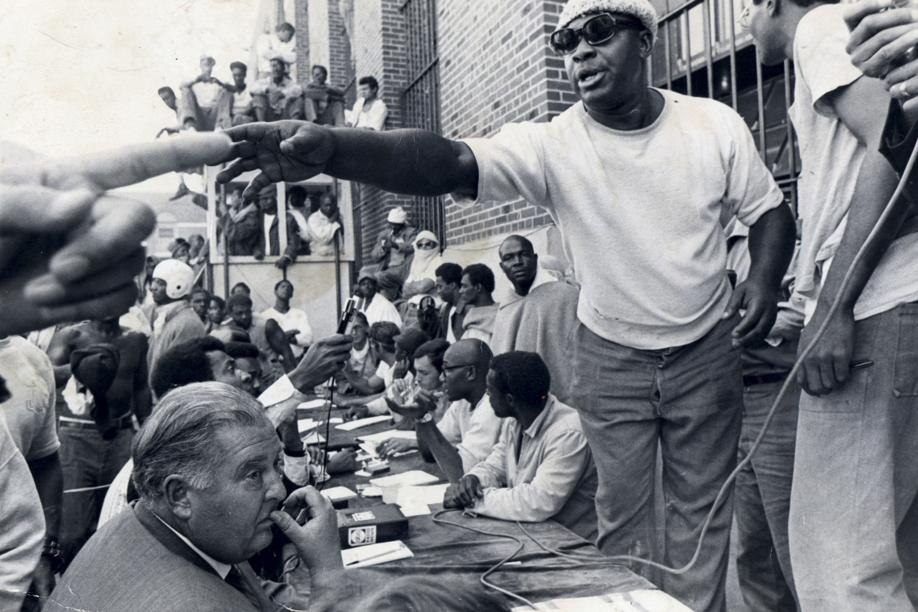

Mr. Jelinek was at a law firm in 1965 when he volunteered to work during the summer for the Lawyers Constitutional Defense Committee of the American Civil Liberties Union, representing mostly workers from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC.

As a civil rights lawyer in the South, he was shot at and was arrested once for practicing law without the permission of the Alabama bar.

He also directed the Southern Rural Research Project, which documented rural malnutrition and sued the Agriculture Department to distribute surplus commodities to the hungry and to force recalcitrant county officials to participate in the federal food-stamp program.

He moved to California, where he represented Native Americans who seized Alcatraz Island in 1969; they claimed title under a 19th-century treaty and aired their other grievances against the federal government during a 19-month occupation.

Mr. Jelinek practically lived on the island, raised money for the protesters, and helped persuade prosecutors to level relatively minor charges. (Three demonstrators were convicted of stealing copper piping, a verdict overturned on appeal.)

In 1971, he was recruited to coordinate the defense of 61 inmates charged with nearly 1,300 crimes after the Attica prison riot in western New York, which left 10 corrections officers and civilian employees and 33 prisoners dead. All but one guard and three inmates were killed by the authorities in what a prosecutor branded a wanton State Police “turkey shoot.’’ Over decades of litigation, the inmates were gradually cleared of additional penalties.

Mr. Jelinek also represented conscientious objectors during the Vietnam War and served three terms on the Berkeley City Council.

Donald Arthur Jelinek was born in the Bronx , the son of Jewish immigrants. His father, Eugene, ran a print shop. His mother, the former Adele Schneider, was a secretary. He grew up near Yankee Stadium, graduated from the Bronx High School of Science, New York University, and New York University Law School, living in Greenwich Village and paying his rent by working as a janitor.

He met his first wife, the former Estelle Cohen Fine, in the South. Their marriage ended in divorce.

In addition to Scherr, he leaves her daughters, Dove and Apollinaire Scherr; two grandchildren; and his brother, Roger.

Inspired by the Portraits of Grief articles in The New York Times about the victims of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Mr. Jelinek told a website for veterans of the civil rights movement in 2005 that he and his wife had already discussed his epitaph.

“I told her that if I had been one of them,’’ he said, “I would want her to write: ‘He had people who he loved and who loved him . . . and he was part of SNCC.’ ’’