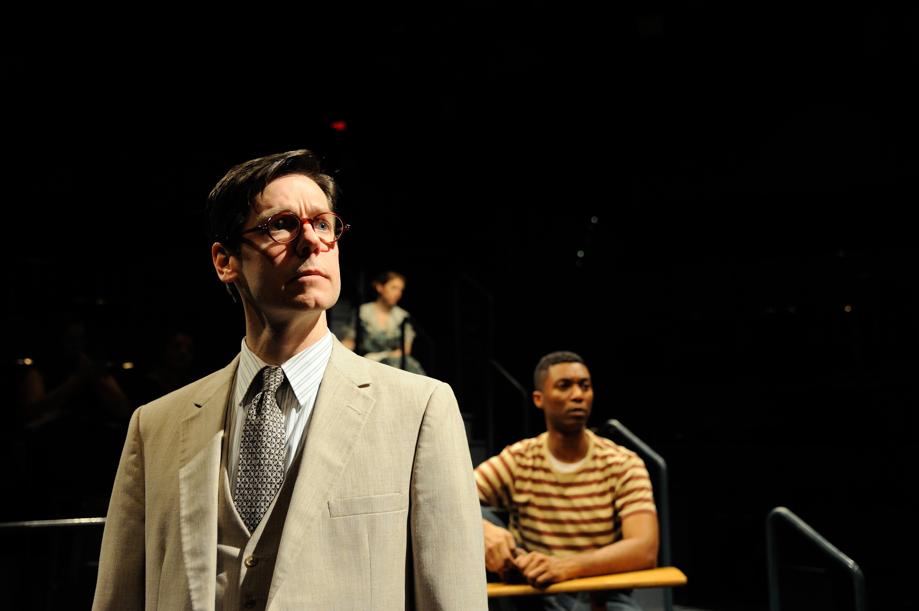

In “To Kill a Mockingbird’’ at Trinity Repertory Company, attorney Atticus Finch (Stephen Thorne) delivers a passionate speech in defense of Tom Robinson (David Samuel), a black man falsely accused of rape, while Robinson looks silently on.

It’s meant to be a stirring moment in Christopher Sergel’s 1990 stage adaptation of the 1960 novel by Harper Lee, who died last month. But the scene, and the story, carry an unavoidable whiff of paternalism: a heroic white man speaking for a helpless (and ultimately doomed) African-American, or, as Finch describes Robinson, “a quiet, respectable Negro man.’’

That brings us to the heart of the issue facing a major new adaptation of “Mockingbird,’’ to be scripted by Aaron Sorkin (“The West Wing,’’ “The Social Network’’) and headed for Broadway. At a time when African-Americans tell their own stories, in the theater and elsewhere, there’s no getting around the fact that the white-savior narrative of “Mockingbird’’ feels awfully dated.

When it comes to race, “Mockingbird’’ simply can’t speak in a voice anywhere near as urgent as those belonging to contemporary black playwrights. In our present fraught moment, it is their unflinching takes on racial disparities and attitudes that cut deepest, they who can trace the complex strands of African-American identity in an increasingly diverse country.

This is not to denigrate Lee’s landmark novel. Her sharp, richly detailed portrait of childhood — and of the ways that our parents and the wider world of adults slowly start to come into sharper focus — still rings true. Published amid the civil rights movement, “To Kill a Mockingbird’’ was a powerful statement against bigotry, and since then it has delivered important lessons to generations of students. Certainly its theme of racial injustice in the realm of law enforcement has relevance to our own time.

But a lot can be lost in translation from page to stage. Moreover, the reality is that as cultural contexts change, so does the resonance and meaning of certain works of art. The 1962 film version of “To Kill a Mockingbird’’ — in which Gregory Peck played Atticus Finch as an all-knowing pillar of rectitude and won an Academy Award in the process — registers today as one of those movies designed to make white people feel better about themselves.

That is emphatically not the goal of works by black playwrights like Boston-based Kirsten Greenidge or Emerson College artist-in-residence Daniel Beaty or a host of other African-American writers whose work has been produced in the Boston area over the past couple of years. Taken together, these works have dramatized and crystallized critical and timely questions on race, forcing audiences to consider how we look at one another and how far, really, we have come. What these dramas deliver are not one-dimensional portraits of passive figures but instead multifaceted characters who push back against specific cultural pressures, including racism, as they try to live their lives. While they may win partial victories in the face of racial inequality, it’s made clear that similar struggles will continue to unfold in the real world after the curtain falls.

Greenidge’s “Baltimore,’’ which premiered last month in a coproduction by the Boston Center for American Performance and New Repertory Theatre, used an explosive episode of campus racism to ask whether even college students in 2016, near the end of Barack Obama’s second term in the White House, can really be considered a “post-racial’’ generation — and whether such a thing is even possible. Another drama by Greenidge, “Milk Like Sugar,’’ presented last month at Huntington Theatre Company, revolves around Annie, an African-American high school student from a working-class family who resists pressure to join her friends in a pregnancy pact. Implicit in the play is a question for all of us: Why don’t Annie and her friends feel they have other options? Why don’t they see a path to a different future?

Black playwrights have challenged us to ponder the lingering effects on present-day attitudes of long-ago racial constructs devised as part of popular entertainment (Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s “An Octoroon,’’ copresented by Company One Theatre and ArtsEmerson last month, and George C. Wolfe’s “The Colored Museum,’’ seen at Huntington Theatre Company last year); the disrespectful treatment of black veterans when they return home from war (Katori Hall’s “Saturday Night/Sunday Morning,’’ presented at Lyric Stage Company of Boston last fall); the challenges of growing up black and gay (Robert O’Hara’s “Bootycandy,’’ at SpeakEasy Stage Company starting this weekend); and the implications of research suggesting that prejudice may be an innate part of the way our brains are hard-wired (Lydia R. Diamond’s “Smart People,’’ at Huntington Theatre Company in 2014).

While far from Pollyanna-ish, Beaty’s “Mr. Joy,’’ presented at ArtsEmerson last fall, exuded hope that a neighborhood that sticks together (in this case, Harlem) can endure in the face of tragedy, gentrification, gang violence, institutional racism, and police brutality. In “Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3,’’ presented at American Repertory Theater last year, Suzan-Lori Parks traces the journey of a slave from Texas to a Civil War battlefield while exploring what it means to be free. In “How I Learned What I Learned,’’ now at Huntington Theatre Company, the late August Wilson reminds us of the everyday affronts that come with being black in America.

Further reminders have come in the form of grim news reports about the deaths of African-Americans at the hands of police. The Black Lives Matter movement has arisen in response. Over the past couple of weeks in the presidential campaign, Republican frontrunner Donald J. Trump has come under fire for initially declining to disavow the support of white supremacist David Duke, while black voters have proven vital to sustaining the candidacy of Democrat Hillary Clinton. The absence of African-American nominees in the Academy Award acting categories led to a backlash on social media under the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite and a monologue by host Chris Rock last month that was laced with references to the controversy.

Near the end of “How I Learned What I Learned,’’ the great August Wilson, played by Eugene Lee, looks back on his life and says that “some roads have opened to me’’ while other roads “have bred landscapes of severe wolves to blunt and discourage my advance,’’ and still others “shall remain closed in some things forever.’’ Then he adds: “Yet I do not stand here and say that we African-Americans are victims, but rather we both, black and white, are victims of our history and our victimization leaves us staring at each other across a great divide of economics, privilege, and the unmitigated pursuit of happiness.’’

It’s no slight to Aaron Sorkin, or to Harper Lee for that matter, to suggest that the new stage version of “To Kill a Mockingbird’’ is unlikely to deliver insights on race that can match those of Wilson or the new generation of black playwrights he helped to inspire.

“TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD,’’ Page N6

Don Aucoin can be reached at aucoin@globe.com.