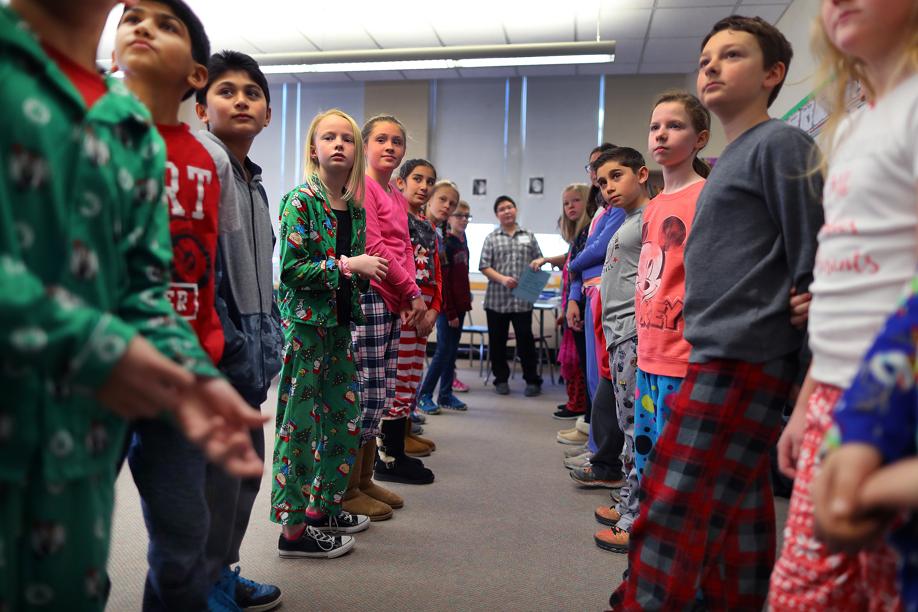

This is how 18 children in Rachael Levine’s fifth-grade class at the Lowell Elementary School in Watertown learned empathy.

First, they gathered in two lines at the front of the classroom, avoiding eye contact until a visiting middle-school student asked them to face each other and divide into pairs. Then, they were instructed to read a few questions posted on the board.

The children would have five minutes to interview each other. Afterward, they would return, pair by pair, to give their reports, introducing friends as if they were strangers, sharing what they’d learned as if it was their own story.

Kingian Nonviolence Training had begun.

Kingian Nonviolence is a philosophy and technique developed in the 1960s by the late civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who borrowed from Jesus, Thoreau, and Gandhi to create a strategy for peaceful protest: marches, sit-ins, and other forms of civil disobedience aimed at ending racism, poverty, and social injustice.

The training was formalized by King’s surviving colleague and friend Dr. Bernard Lafayette, who since King’s assassination almost 50 years ago has brought the course to 90 countries and 30 states, including Massachusetts.

It was Lafayette who promised King that he would share the work that would become King’s legacy. And it was Lafayette who made a trip to Watertown in April to speak with school and civic officials about starting a training program in the school district.

“This is so needed,’’ Lafayette said during a phone interview. “In Watertown, I was so impressed with the people in training — teachers, police officers, youth . . . a different generation and different professions to help train the others.’’

Some say the training, which emphasizes reflection and self-awareness, couldn’t have come at a better time, given the bitterness of the recent presidential election and reports of escalating racism everywhere.

“A joke rises up to become more serious,’’ said Jordan Laudani, 13, an eighth-grader who visited the fifth grade with five classmates and middle school Spanish teacher Ruth Henry, to teach King’s course.

The training has received a warm reception inside the Watertown school district, considered the first in the country to have adopted the program districtwide. It has also been embraced by the Watertown Police Department and World in Watertown, a grass-roots group that promotes social justice through education and social programs.

“The timing is really important. We wanted the Police Department on board, to have as much community policing as possible,’’ said Will Twombly, a founder of World in Watertown. “Since the election, immigrants are feeling frightened and uncertain. There’s a rise in hate crimes, particularly against Muslims.’’

According to interim schools Superintendent John Brackett, 49 different languages are spoken in students’ homes; children in Levine’s fifth-grade class include newcomers from Armenia, Norway, Guatemala, Syria, Pakistan, and Ireland.

“We don’t give our own political views,’’ said Ruth Henry, the middle school teacher who heads up the district’s Kingian Nonviolence Training. “But it’s important that school is still a safe place for everybody.’’

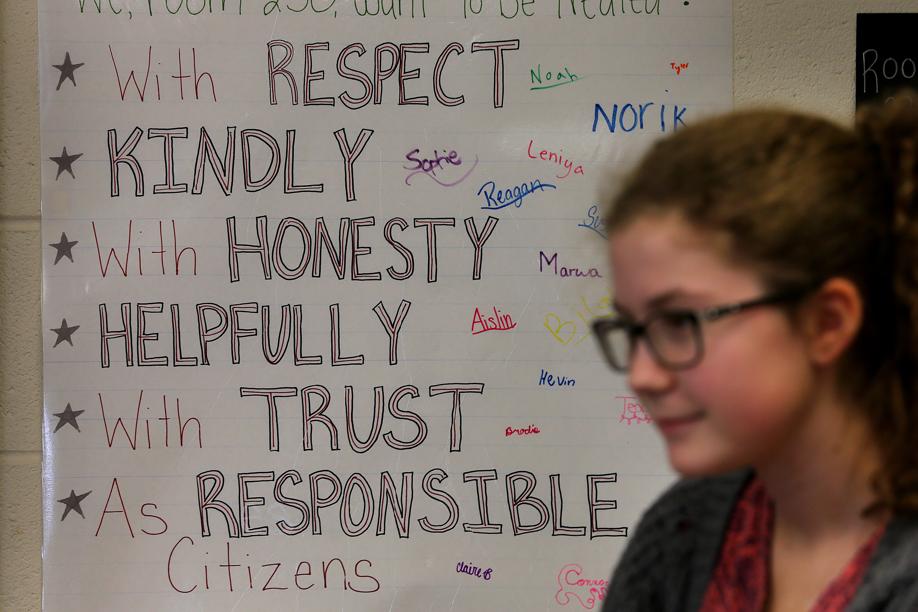

Students, teachers, police officers, and others who take the training are steeped in King’s ideas about nonviolence. The training emphasizes social conditions: Rather than targeting individuals or groups, it focuses on situations — and problems.

But at the heart of the curriculum are lessons in listening.

“It’s really important to think more about putting yourself in the shoes of the other person,’’ said Lieutenant Dan Unsworth, a 20-year veteran of the town’s police force who oversees community policing and took the training last summer with two other police officers, 17 teachers, and 15 students.

Students say the training — and certification to teach it — have changed them.

Middle school trainer Jordan Laudani noticed he was getting into fewer fights during hockey games and chalking up fewer penalties after he took the course and started teaching it to others.

“I thought conflict was an argument that happened and ended,’’ said Robert Yildirim, a seventh-grader who completed the course and was among the middle schoolers who trained the fifth-graders. “I learned that conflict is healthy. I learned that conflict has history. I had no clue.’’

When conflicts arise, it’s situations, not people, that need to be changed, Kingian Nonviolence Training teaches.

“The point is, you have to appreciate nonviolence,’’ Lafayette said. “You have to be convinced it’s an important kind of resource.’’

But what do you do if you find yourself in a fight?

“We want you to remember what’s important to both of you: You can say to your friend, ‘Remember when we were in class? What are we doing fighting?’ ’’ Ruth Henry told the fifth-graders.

Henry credits retired superintendent Jean Fitzgerald for bringing King’s nonviolence training to Watertown, which Brackett, the district’s interim superintendent, has continued to support.

“Now, maybe more than ever,’’ Brackett said in an e-mail, “the principles are vital for us to remain an open, welcoming, respectful, and supporting community of learners.’’

Hattie Bernstein can be reached at hbernstein04@icloud.com.