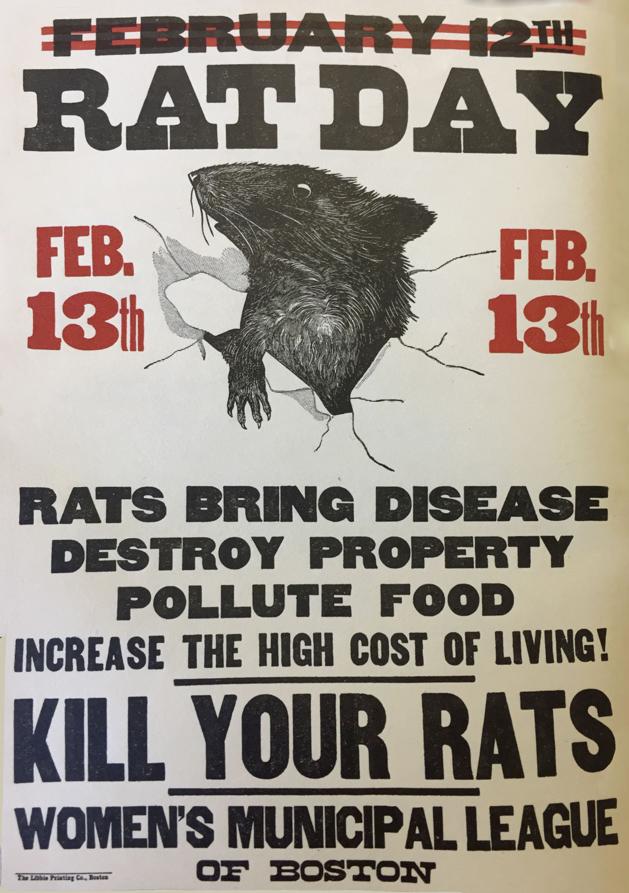

As World War I was raging overseas, another war of sorts was brewing here in Boston. One hundred years ago, on Feb. 13, 1917, the city sought to combat a growing vermin problem by launching its first (and, notably, last) Rat Day.

Like an engineered armageddon, Rat Day was created to entice Bostonians to decimate the city’s rodent population on a single day in exchange for cash prizes. If the event proved a success, “rat clubs’’ and ongoing “competitive killings’’ would become part of Boston culture.

Rat Day was the brainchild of the Women’s Municipal League of Boston. Founded in 1908 and boasting 2,000 members by 1917 — many from prominent families — the league focused on boosting the morality and cleanliness of a rapidly growing city. Boston’s thriving rat population was an easy target for such crusading women. As a major Atlantic port, Boston had been hit in 1798 with bubonic plague, which struck New Orleans and San Francisco as recently as 1914 and 1907 respectively.

While rat populations swelled, the well-bred members of the municipal league stressed that achieving cleanliness — not just of the home, but of the whole city — was a civic duty. Today, a major city might address a rodent problem with chemicals deployed by specialized pest-control workers, or perhaps with high-tech traps and other cutting-edge technology. Rat Day embodied a far different mindset: the hope that concerted, coordinated action by everyday Bostonians from all walks of life could solve a public health threat.

Members of the league enlisted immigrants in their cleanup campaign. Hundreds of thousands of pamphlets and fliers — in such varied languages as English, Italian, Polish, and Yiddish — detailed the perils of the wily rodent and how to stymie its population growth. These pamphlets were circulated around the city to build anti-rat sentiment.

Rat Day was originally planned for Feb. 12, but was changed when some objected to Boston’s slaughterfest coinciding with Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. In haste, the day was pushed to Feb. 13, nicely paired with Valentine’s Day.

In spite of ample media attention, Boston’s Rat Day was a great disappointment. Bitter cold weather combined with confusion about the date resulted in a tally of fewer than 1,000 corpses. That said, an impressive 30 percent of this total — 282 carcasses — came from just one Brighton man, who won $150 (more than $2,800 today) in prize money.

The Women’s Municipal League blamed lackluster turnout on bad PR. “The people were not sufficiently impressed with the danger to give the support necessary,’’ it was later reported in the group’s dispatch.

A century later, the rat race continues in cities across the country. Members of the Ryders Alley Trencher-fed Society (R.A.T.S.) in New York City, formed in 1995, prowl alleys with their dogs on weekend nights, eager to unleash their pups’ killer instincts so often repressed in the modern domesticated world. The hunt lasts as long as the dogs show enthusiasm — anywhere between two and six hours. The average tally is between 30 and 50 kills. R.A.T.S. maintains a mailing list of about 65 people who have brought their dogs to the hunt. And there are rules: On urban excursions, only one dog per handler is allowed, and there’s an eight-dog limit — a number “which gives us maximum efficiency but not a mob that will disrupt the neighborhood or cause a scene,’’ says founding member Richard L. Reynolds.

As a pest-control strategy, the notion of hunting rodents down one by one, with or without canine assistance, seems futile. In the end, rats just breed too quickly. But for its time, Rat Day was noble for what it represented: a belief in the power of civic ritual to address common problems — and bind an increasingly diverse city together.

Ray Cavanaugh is a freelance writer.