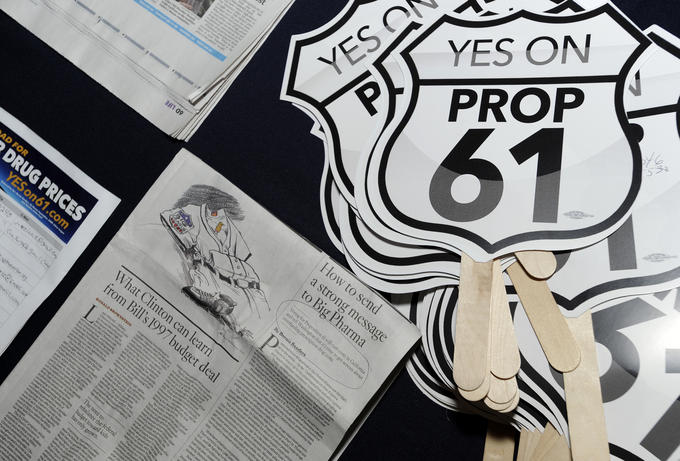

As Americans grapple with the rising cost of medicines, a contentious ballot measure in California is being billed as a fix to an intractable national problem.

Known as Proposition 61, the proposal would require state agencies to pay no more for prescription drugs than the US Department of Veterans Affairs, which receives a federally mandated 24 percent discount from manufacturers. In theory, that would lower drug costs for up to 7 million California residents — including low-income residents on the state version of Medicaid — who get insurance coverage through various state agencies.

Supporters, including Senator Bernie Sanders, maintain the measure will make it harder for “greedy’’ drug makers to pursue “price gouging.’’ For its part, the pharmaceutical industry warns there will be “unintended consequences,’’ such as higher prices on some drugs or fewer choices for some state residents.

This is a close call, because the measure has merits and flaws. Ultimately, the California Drug Price Relief Act is a well-intentioned proposal that clearly sends a strong message to the pharmaceutical industry — but the details should also give us pause.

“The polls show most people support it. They’re speaking up and saying they’ve had enough,’’ says Walid Gellad, the codirector of the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh. “But is this the right way to address prices or will it cause problems elsewhere?’’

The measure gives citizens a chance to respond directly to rising drug costs, as opposed to relying on their legislators to try to rein in price hikes, a strategy that so far hasn’t succeeded. Moreover, Prop 61 is seen as a litmus test, because if it passes in California, similar measures may well pop up in other states. There’s already a similar measure on the ballot in Ohio for 2017.

“The drug industry sees this as an apocalypse,’’ says Michael Weinstein, president of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, a nonprofit that runs pharmacies and clinics nationwide. Weinstein spearheaded the California ballot initiative, along with the upcoming Ohio vote.

Indeed, Eli Lilly chief executive John Lechleiter last week said “we’re fighting this tooth and nail.’’

At first blush, it would seem the measure — which is being fought in expensive ad campaigns — is a straightforward salve. If it passes, it could start driving down prices around the country, because Medicaid programs in other states would be legally entitled to get the same prices negotiated by most California state agencies.

But it’s not really so simple. Notably, there are unanswered questions about the effect on the California Medicaid program, which is called Medi-Cal, and whether it really could get all the medicines residents need at a lower price. For instance, what happens if a drug maker refuses to abide by the rules set out in Prop 61 and balks at offering the same discount to Medi-Cal that it gives to the VA? Medi-Cal is still mandated by federal law to provide that medicine to its beneficiaries. This conundrum may wind up in the courts.

Medi-Cal could seek a waiver from the federal government to stop offering the drug to its members, but this option appears uncertain, at best.

Why? States generally don’t seek such waivers because the federal government rarely approves them, according to a source in the California Department of Health Care Services. Moreover, it’s not practical to submit a waiver every time the VA price can’t be matched.

There is another potential wrinkle.

The VA also negotiates additional rebates for some drugs, but those extra rebates, which are paid to the agency, are not always disclosed. California agencies could learn about them by filing Freedom of Information Act requests, but this would take too much time to be practical, since the agencies must ensure drugs are available when needed. Drug makers, meanwhile, may respond by raising the prices they charge to the VA or by refusing to sell certain medicines to the state rather than accepting a much-reduced payment, according to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office. The pharma industry could also raise prices for other residents to make up for any losses it’s forced to take in Medi-Cal.

For these reasons, the legislative analyst’s office is uncertain whether Prop 61 will have “relatively little effect’’ or yield “significant annual savings.’’

“It sounds great, but details matter,’’ said Kathy Fairbanks, a spokeswoman for the industry campaign opposing Prop 61. “It would raise prices and decrease access. And it doesn’t offer guidance for how it will work in the real world.’’

Some of these points may be valid, but then again, list prices for brand-name drugs rose an average of 12 percent last year. Some companies are raising prices sky high. And a new poll says that 63 percent of Americans want the government to take action.

How do drug makers respond to this public outcry? By donating $109 million to fight the ballot measure and paying another $100 million in dues to their national lobbying group to thwart future initiatives. Talk about a tin ear. That money could be used to research new treatments.

Prop 61 is imperfect and, ideally, pricing should be addressed on a national level. But the measure sends a needed message that the status quo is unsustainable. Until the pharmaceutical industry recognizes this sad reality, there will be more — and better — propositions before voters.

Ed Silverman can be reached at ed.silverman@statnews.com. Follow him on Twitter @Pharmalot. Follow Stat on Twitter @statnews.