In the 2012 presidential election, residents of the Merrimack Valley town of Boxford voted the same way they had for over a generation: Republican. Forty miles to the south, Randolph voters overwhelmingly backed the Democratic ticket, just as they had for decades.

The familiar narrative is that Massachusetts is among the bluest of states, a Democratic Party stronghold with an idiosyncratic penchant for electing Republican governors. But a Globe review of presidential election data going back to 1972 shows a more complex picture of the Commonwealth’s varied communities.

It’s a picture that, come the morning after Election Day, may help explain if some local results are out of synch with the rest of the state.

“There are a lot of independents in Boxford, but most are Republicans at heart,’’ said Lee McMahon, a Democrat who retired to Boxford, known for its scenic farms and ponds, about five years ago.

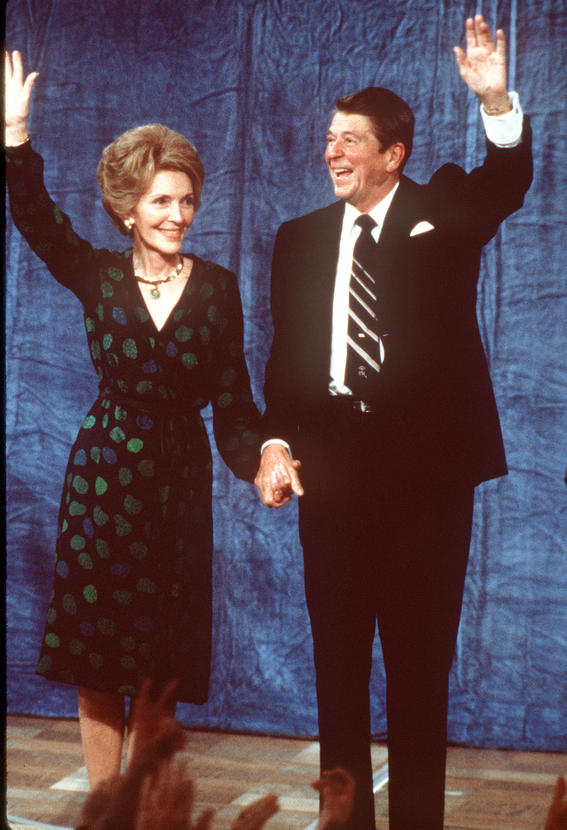

The state has leaned Democratic since 1928, when voters backed Al Smith’s futile run against Herbert Hoover. In the past 88 years, Massachusetts has supported Republican presidential candidates only four times: voting twice for Dwight D. Eisenhower and twice for Ronald Reagan.

However, a closer analysis shows almost as many Greater Boston communities supporting Richard Nixon in 1972 and Gerald Ford in 1976, though larger, more urban communities were more likely to support Democrats.

Grouped together, communities west and north of Boston have followed statewide voting patterns closely over the years. But towns south of Boston went further in support of Reagan in 1980 and 1984, and most of those communities remained in the GOP column in 1988, while the state as a whole supported Democrat and then-Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis.

Statewide and throughout Greater Boston, Bill Clinton significantly outperformed George H.W. Bush in 1992, though independent candidate H. Ross Perot stripped away many votes that otherwise may have gone to Bush. In fact, Perot topped the ticket in a dozen Massachusetts communities, including Middleborough, Rochester, and Tyngsborough.

Clinton won about 60 percent of the statewide vote in 1996, and since then Democratic candidates have captured 59 percent to 62 percent of the Massachusetts vote every year, even as the nation elected George W. Bush in 2000 and reelected him in 2004.

Clinton’s folksy appeal failed to sway voters in Boxford throughout the 1990s, though, and the rural town was among relatively few communities statewide that favored John McCain over Barack Obama in 2008.

Peter Ubertaccio, a political science professor at Stonehill College in Easton, said town-by-town results are largely explainable by demographic trends.

“If you overlaid those maps with other kinds of data in terms of who has a college degree; what kind of occupations are we looking at; what are the breakdowns by race, ethnicity, religion, or religiosity, you’re going to see some overlapping trends across cities and towns,’’ Ubertaccio said.

Among 160 communities across Greater Boston, Boxford is the only one that has supported Republican presidential candidates exclusively since Nixon in 1972, the earliest year data are available from the secretary of state’s office.

The bucolic community of 8,000 residents is zoned for lots with a minimum of 2 acres and has high property values. Its mostly upper-middle-class population is politically mixed but “very fiscally conservative,’’ according to Gerald R. Johnston, Boxford’s elected town moderator.

“Boxford is very much of a bedroom town,’’ said Johnston, 69. “It is 24½ square miles without a single traffic signal.’’

Boxford’s population is 92 percent white, according to 2014 census data, and has a median household income of nearly $128,000.

In contrast, the town of Randolph, which has voted Democratic consistently across the last 11 elections, has a median household income less than half of Boxford’s — just over $63,000 — and a population that was 41 percent black and 38 percent white as of 2014.

With a population of about 33,000, Randolph also has seen more immigrants from Haiti and Vietnam, according to Jason Adams, president of its Town Council.

“There’s a high population of very progressive people here in Randolph,’’ Adams said. “It’s a melting pot, and I love living here.’’

Boston and Cambridge have thrown their votes behind every Democratic presidential candidate since 1972, as have Arlington, Brookline, Newton, and Watertown in the western suburbs, and a cluster of communities north and east of the Hub that includes Chelsea, Everett, Lynn, Malden, Medford, Revere, Somerville, and Winthrop.

Communities such as Beverly and Natick have gone Democratic most years, but they shifted briefly to the GOP column in 1980 and 1984, in line with the statewide trend.

Natick, with a population of 33,000 in 2010, has an income level squarely between Boxford and Randolph, falling just shy of $99,000 in 2014.

Perhaps best known for its many retail stores along Route 9, the town also has a historic common surrounded by downtown shops. It’s a community in flux, locals say, as historic farms give way to condo developments and property values rise.

“It was affordable when we first moved,’’ said Diana Bolick, who came to Natick 22 years ago. “But I don’t know if it is now.’’

This November, as in past elections, Natick is likely to go with the rest of the state in giving a majority of its votes to Hillary Clinton. About 4,600 Natick residents voted for Clinton in the Democratic primary, compared with just under 1,400 votes for Trump in the crowded GOP field.

Statewide, Clinton garnered nearly twice as many votes as Trump, and polls have shown her with a strong lead. A mid-September poll conducted by WBZ and the University of Massachusetts Amherst showed Clinton leading Trump by 13 percentage points.

Erin O'Brien, chairwoman of the political science department at the University of Massachusetts Boston, said Clinton’s lead is unlikely to go away.

“I am the most risk-averse person in the world, but I would definitely bet my mortgage on it,’’ O’Brien said. “She’s so far up, there’s such an advantage between those enrolled Democrat and those enrolled Republican, and . . . Massachusetts Republicans are far from enthralled with this guy.’’

But with the right candidate, the balance could tilt in 2020 or 2024.

Michael Kryzanek, a political science professor emeritus at Bridgewater State University, said the Massachusetts Democratic Party has long relied on a superior ground game, but that advantage hasn’t stopped the state from electing Scott Brown to the US Senate in 2010 and tapping four Republican governors since 1990, including the widely popular Charlie Baker.

“If Republicans, whether it’s at the national level or at the state level, put out an attractive candidate,’’ Kryzanek said, “that individual is going to be competitive and ultimately be victorious.’’

Matt Rocheleau of the Globe staff and correspondents Jacob Carozza, Debora Almeida, and Vanessa Nason contributed to this report. Jeremy C. Fox can be reached at jeremy.fox@ globe.com.