Odyssey Opera

At Boston University Theatre, June 3 and 5 (“Ezio’’) and June 8, 10, and 12 (“Lucio Silla’’). Tickets: $30-$120. 617-826-1626; www.odysseyopera.org

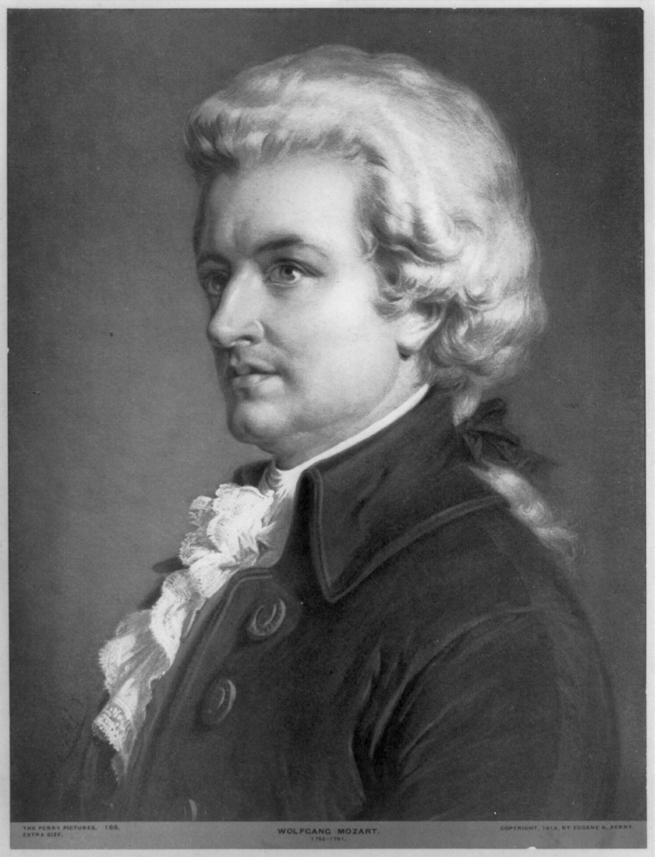

“Consider the tumults in ancient Rome,’’ John Adams once advised, “and compare them with ours.’’ This summer, Odyssey Opera makes the same invitation. Beginning June 3, conductor Gil Rose’s company will mount a mini-festival of two operas, both borrowing (however loosely) their milieu and personae from the grandeur that was: Christoph Willibald Gluck’s “Ezio’’ and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “Lucio Silla.’’ Both works are, like so many other depictions of the classical world, equal parts entertainment and rubric, spectacle and warning. No matter how many eras intervene, Roman stories seem to mirror the world with uncanny fidelity.

Take “Ezio’’: The libretto, by the prolific and popular Pietro Metastasio, freely spins historical characters (the Roman general Flavius Aetius, the emperor Valentinian III, and the Roman senator Petronius Maximus, set on poisoning Valentinian’s mind against Aetius) into a romantic melodrama far removed from history. (For one thing, Metastasio reconciles Ezio — that is, Aetius — and Valentinian; in reality, the emperor killed his general with a sword to the head.) But Metastasio brings out tensions between authority and liberty, allegiance and honor, that are both typically classical and perennially contemporary.

“The more I look at it, the more and more it seems appropriate and topical,’’ says Joshua Major, the stage director for Odyssey’s “Ezio.’’ In particular, Major is fascinated with Massimo, the opera’s version of Maximus, and his campaign of insinuation against Ezio — a quintessential example of “how information is spun.’’ There’s also the way that personal conflicts ripple through the political sphere: “These public figures present a very private drama.’’

Isabel Milenski, the director of “Lucio Silla,’’ also sees parallels. Mozart’s title character is another actual figure — the historical Sulla, the Roman general who infamously marched his army on Rome — though Mozart’s opera (to a libretto by Giovanni de Gamerra that was heavily script-doctored by Metastasio) is more concerned with the dictator’s love for Giunia, the daughter of a political enemy. Still, Milenski finds both Sulla and his operatic double much like all dictators: “They all had blood on their hands,’’ using power and violence to acquire land and wealth and power—“It’s all sounding familiar, isn’t it?’’

For Milenski, the charge in the drama’s current is how Silla is a product of his environment, how his feelings of love for Giunia are warped by his military training and ruthless political reflexes into more vicious impulses. Milenski even finds a hopeful echo in the plot’s unlikely resolution, how, in the opera’s last few minutes, Silla’s heart abruptly changes. “Maybe it only takes a few minutes,’’ she says, to see other ways of living: “What is another paradigm for ourselves that’s not just brute force?’’

Both operas are relatively early efforts by each composer. “Ezio’’ is being presented in its earlier, 1750 version, pre-dating the radical dramatic reforms Gluck would bring to his later operas; what’s already there, for Major, is “the humanity,’’ Gluck’s empathy for real, recognizable emotion among the dramatic stylization. “Lucio Silla’’ was premiered when Mozart was only 16, but Milenski highlights its unrelenting virtuosity, its “death-defying’’ demands on the singers (“It’s a sporting event,’’ she marvels) as a premonition of the cascading intensity of the composer’s late and similarly Roman “La Clemenza di Tito.’’ The profuse style is Mozart’s way of “exploiting every possible nuance, every possible turn of emotion,’’ Milenski says.

Ultimately, that emotion — and the high-wire vocals that carry it — take center stage. “Lucio Silla’’ Milenski says, is “very much about the musical fireworks, the musical and dramatic spectacle.’’ Major agrees: “Ezio’’ is, first and foremost, “a very dramatic context for really great singing.’’ But of course spectacle and show were at the heart of Roman power; and the way the operas yoke them together only reinforces the continuing lessons of ancient history. “Has there ever been a nation who understood the human heart better than the Romans, or made a better use of the passion for consideration, congratulation, and distinction?’’ John Adams wondered. “Reason holds the helm, but passions are the gales.’’

Matthew Guerrieri can be reached at matthewguerrieri@gmail.com.