WASHINGTON — Vice President Mike Pence issued a fresh warning to North Korea Monday not to test the United States’ resolve. But behind the threatening talk, the White House is taking a more calculated approach, giving the Chinese government time to show whether it is ready to use its influence to curb its erratic, nuclear-armed neighbor.

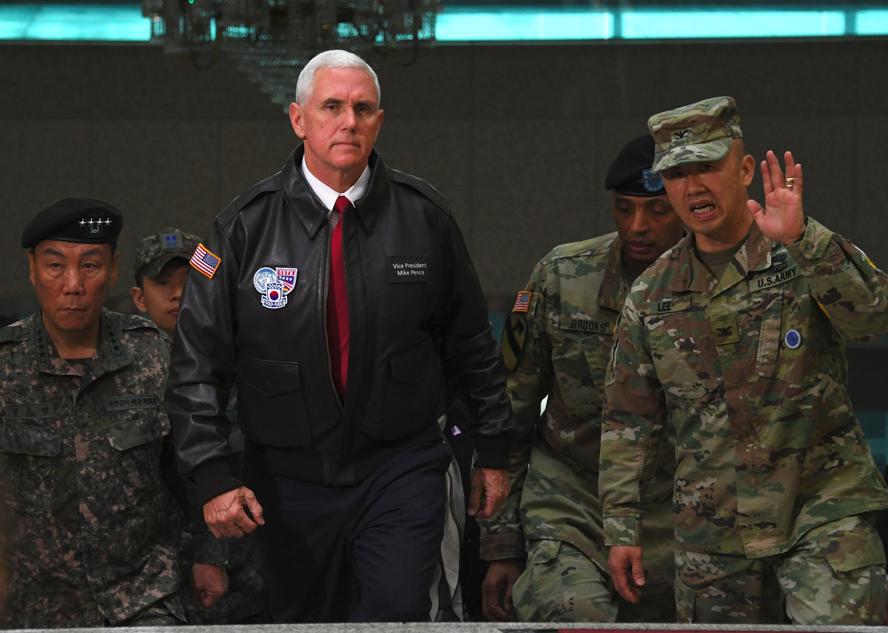

The disparity between the Trump administration’s blunt public statements to Pyongyang and its growing reliance on Beijing has been put in sharp relief by Pence’s visit to South Korea, which included a stop at the Demilitarized Zone that divides the Korean Peninsula.

North Korea should not test “the strength of the armed forces of the United States in this region,’’ Pence declared in Seoul, the South Korean capital. Yet in Washington, White House officials said President Trump would not draw any red lines with North Korea. And officials expressed hope that China was finally playing a more active role in pressuring the North — a strategy that, if successful, could obviate the need for US military action.

“There’s a lot of economic and political pressure points that I think China can utilize,’’ Sean Spicer, the White House press secretary, said at his daily briefing. “We’ve been very encouraged with the direction in which they’re going.’’

Spicer pointed to China’s cutback of coal imports from North Korea as evidence of its new resolve to curb the provocative behavior of its neighbor. But the Chinese government made the decision to stop purchasing North Korean coal before President Xi Jinping of China met with Trump this month at Mar-a-Lago, his private club in Florida.

The administration has teed up additional sanctions on North Korea — from grounding its state airline to banning exports of its seafood — depending on its behavior, according to officials briefed on the policy. The White House is also considering targeting Chinese banks that do business with North Korea, these people said. But it is holding off on that step, which would antagonize Beijing, until it sees what China does.

Few of the unilateral sanctions are likely to change North Korea’s behavior, and most would simply be recycled proposals from the Obama administration. So despite insisting it has mothballed the previous administration’s policy of “strategic patience’’ on North Korea, the Trump administration finds itself in the familiar position of waiting.

Pence even held out the possibility of opening talks with the North Korean regime, noting that Washington was seeking security “through peaceable means, through negotiations.’’

The Trump administration’s mixture of resolve and ambiguity attested to its quandary with North Korea. Though the North Korean dictator, Kim Jong Un, refrained from detonating a nuclear device and suffered another failed missile test this weekend, the United States has not yet found a way around the limited options against the North.

Trump essentially has three choices: a military strike that could ignite a full-blown war; pressure on China to impose tougher sanctions to persuade the North to change course, an approach that failed for Barack Obama as president; or a deal that could require significant concessions, with no guarantee that North Korea would fulfill its promises.

The question is whether his apparent willingness to consider both war and a deal may be enough carrot and stick to persuade China to apply enough pressure to bring the North to the table.

Talks have long been China’s preference, and now that Trump seems to be relying on Beijing to an extraordinary degree, Pence may have been signaling that the United States is open to them. China’s chief objective is to get talks — of any kind — started to avoid conflict so close to home.

War on the peninsula is a nightmare for China that could lead to at least 1 million casualties, according to some estimates, ravage the Koreas, and set back Beijing’s climb to global pre-eminence.

In his most flexible language yet, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, on Friday appealed again for negotiations. “As long as it is a talk, China is willing to support it: either it is formal or informal, one-track or dual-track, bilateral, trilateral or quadrilateral,’’ Wang said in Beijing.

On Monday, the State Department’s acting assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific affairs, Susan Thornton, said that North Korea would need to make a definitive change in its nuclear or missile programs before the United States would consider renewed talks.

The administration wants “a signal that they realize the current status quo is not sustainable,’’ Thornton said, although she refused to specify what signal would be acceptable.