From Hollywood musicals to classical ballet, dance has served to reconcile opposites, mend rifts, and negotiate differences. That bodes well for a US-Cuba détente, since — as can be seen in two documentaries at the Brattle Theatre — the Caribbean island nation has a rich and varied terpsichorean tradition that has already worked magic in restoring old ties and creating new ones.

Emma Christopher’s “They Are We’’ (2014) relates the story of Gangá-Longobá, a small ethnic group of people who were brought as slaves from Africa 170 years ago, but have always maintained their culture and heritage despite brutal persecution from a series of repressive regimes. Christopher showed films of the Gangá-Longobá performing their dance and music to audiences across Sierra Leone in search of the group’s origins. Finally in a remote village a man recognized the traditional performances, and crossing a gulf of time shouted out, “They are we!’’

As the images in Eileen Hofer’s “Horizontes’’ (2015) indicate, the Grand Theatre of Havana has seen better days as the showcase for ballet in Cuba. But even though the rehearsal rooms are scruffy and worn, two young aspiring dancers work hard to keep the tradition alive under the tutelage of the island’s 90-year-old matriarch of classical dance, the prima ballerina assoluta Alicia Alonso.

“They Are We’’ screens at 6 p.m. and “Horizontes’’ screens at 8 p.m. on Monday, June 6 at the Brattle.

For more information go to www.brattlefilm.org.

Ars longa, celluloid brevis

Museums go to extreme lengths and expense to preserve works of art, so why not do the same for films about art? The Harvard Film Archive is doing just that, and recently announced that it’s been given a grant by National Film Preservation Foundation to restore two documentaries about prominent contemporary painters, “Fernand Léger in America: His New Realism’’ (1945) and “Birth of a Painting: Kurt Seligmann’’ (1950).

By doing this, the Archive also restores recognition for the accomplishments of Thomas Bouchard, a Cape Cod artist, photographer, and filmmaker who was dedicated to making documentaries about contemporary dancers and artists. He died in 1984, and in 2014 the attic of his Brewster home was found crammed with 16mm film, most in bad condition. The trove of films, unseen for decades, was entrusted to the archive, which hopes to bring as many as possible back to the screen.

For more information go to www.filmpreservation.org/about/pr-2016-05-18.

Learn from the master

If you missed the last session of Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School, which took place in March in Munich, don’t despair. The enigmatic German auteur and master documentarian (he’s set to release two more docs, “Lo & Behold, Reveries of the Connected World’’ and “Into the Inferno,’’ later this year) will offer a tutorial on the online education platform MasterClass sometime this summer. It includes five hours of seminars, a “downloadable workbook with lesson recaps and supplemental materials,’’ and “Office Hours’’ in which students receive video feedback and a lucky few receive one-on-one tutorials with Herzog.

Pre-registration is now available. In the meantime you might brush up on Herzog’s 24 gnomic life lessons listed in the book “Werner Herzog — A Guide for the Perplexed: Conversations with Paul Cronin’’ which offers tips such as “learn to live with your mistakes’’ and “carry bolt cutters everywhere.’’

For more information go to www.masterclass.com/classes/werner-herzog-teaches-filmmaking.

‘Naked’ and dismayed

Though best known for his classic horror films “Onibaba’’ (1964) and “Kuroneko’’ (1968), Japanese director Kaneto Shindô’s uncategorizable “The Naked Island’’ (1960) stands out as perhaps his most original and significant work.

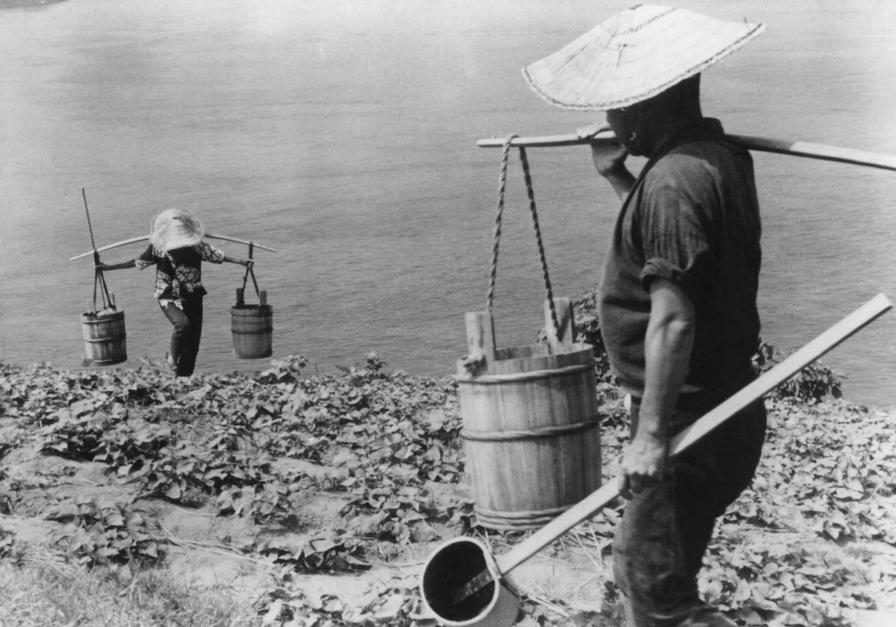

Employing a Robert Flaherty documentary style, shooting in black and white and without dialogue but with an evocative soundtrack and score, he creates a minimalist, allegorical world that aches with seeming reality and also resonates with metaphorical meaning reflecting a post-war Japanese society shifting to the Western capitalist model. Set on a tiny island, it observes a family of four that barely survives by growing sweet potatoes. Since the island has no water, the inhabitants must perpetually row to another island with a well, fill their buckets, and return to irrigate their desiccated crop. Interpret it as you will.

The characters are portrayed by professional actors, the story is fictitious, and the society is invented, but Shindô’s world seems redolently authentic and touches a deeper truth than most straightforward documentaries. Whether it is classified as a documentary or fiction or both, “The Naked Island’’ remains a great, underappreciated work of cinema art.

“The Naked Island’’ is now available from the Criterion Collection in DVD ($29.95) and Blu-Ray ($39.95) editions.

For more information go to www.criterion.com.

Peter Keough can be reached at petervkeough@gmail.com.