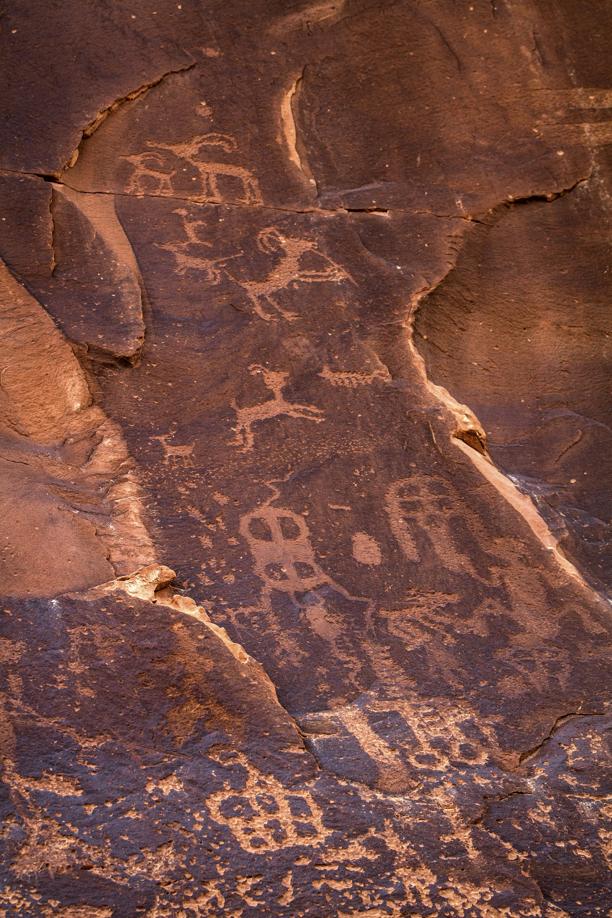

SAN JUAN COUNTY, Utah — The juniper mesas and sunset-red canyons in this corner of southern Utah are so remote that even the governor says he has probably only seen them from the window of a plane. They are a paradise for hikers and campers, a revered retreat where generations of American Indian tribes have hunted, gathered ceremonial herbs, and carved their stories onto the sandstone walls.

Today, the land known as Bears Ears — named for twin buttes that jut out over the horizon — has become something else altogether: a battleground in the fight over how much power Washington exerts over federally controlled Western landscapes.

At a moment when much of President Obama’s environmental agenda has been blocked by Congress and stalled in the courts, the president still has the power under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to create national monuments on federal lands with the stroke of a pen. A coalition of tribes, with support from conservation groups, is pushing for a new monument here in the red-rock deserts, arguing it would protect 1.9 million acres of culturally significant land from new mining and drilling and become a final major act of conservation for the administration.

But this is Utah, where lawmakers are so angry with federal land policies that in 2012 they passed a law demanding that Washington hand over 31 million acres managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service to the state. The US government — the landlord of 65 percent of Utah’s land — has not complied, so Utah is now considering a quixotic $14 million lawsuit to force a transfer.

Conservative lawmakers across the state have lined up to oppose any new monument. Ranchers, county commissioners, business groups, and even some local tribal members object to it as a land grab that would add crippling new restrictions on animal grazing, oil and gas drilling, and road-building in a rural county that never saw its share of Utah’s economic growth. Unemployment here is 8.4 percent, more than double the state average.

“We’ve chosen to live here knowing we’re never going to get rich,’’ said Bruce Adams, a San Juan county commissioner and fifth-generation rancher whose cattle largely graze on federal allotments. “We chose to live here because we love the land, we love the country.’’

To create a new monument out of Bears Ears “would be almost un-American,’’ he said.

But for the coalition of tribes and nature advocates seeking preservation, a new national monument here would preserve a swath of mountains, mesas, and canyons six times the size of Los Angeles. It could also create a new model for how public lands are managed: The tribal coalition of Navajos, Zunis, Hopis, Utes, and Ute Mountain Utes wants to jointly manage the land with the government.