With a few bold pencil strokes, Doffie Arnold brought to life Seiji Ozawa, whose forceful gestures seem to be conducting not just an orchestra, but the entire world.

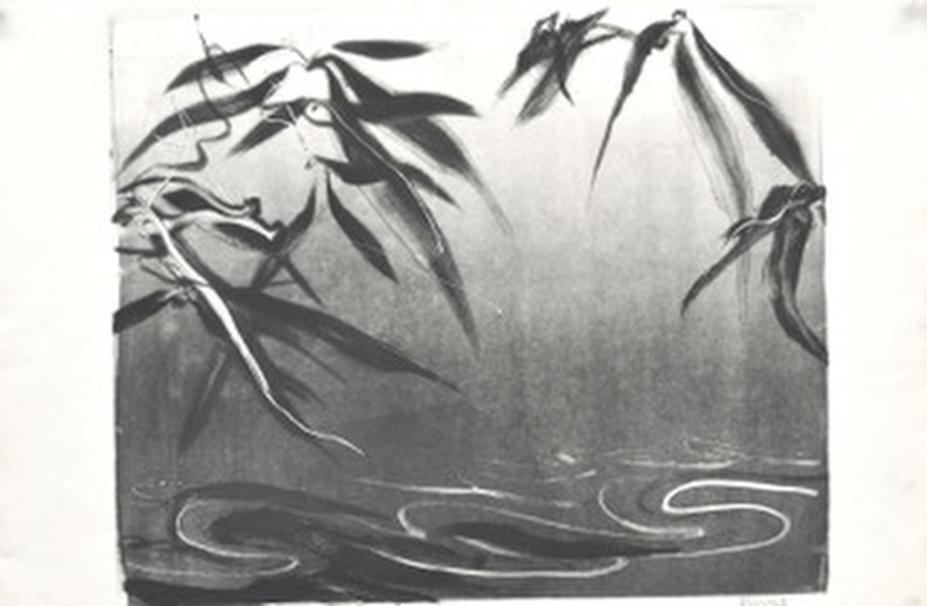

And in one of Mrs. Arnold’s more expansive acrylic paintings, the swirling skies could herald a clearing spell — or a catastrophic storm. So it was in nearly all her work, whether she used pencil, ink, or paint to create a human figure, a landscape, or an abstract.

“In Arnold’s paintings this state of interchange between color and form assume the rhythm of time and its translation into space,’’ the art critic Denise Carvalho once wrote. “Here, the body becomes a tree or a landscape.’’ Elsewhere, Carvalho added, “a landscape melts into floating colors and forms, only to circle back to resemble a body.’’

Mrs. Arnold, who in recent years turned her East Cambridge studio into a place where students in Cambridge schools could take their own first steps toward becoming artists, died May 29 of complications from dementia. She was 94 and had lived in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood after spending much of her life in Concord.

Globe art critic Cate McQuaid wrote in 2002 that Mrs. Arnold “paints with unyielding passion.’’

“She celebrates painting as a means of coming to terms with the suffering and struggle of the world,’’ McQuaid said, reviewing a retrospective of Mrs. Arnold’s work.

“There is a clarity and truthfulness to her art, and a lusty talent, which makes the vivid parade of her work of the last 30 years worth seeing.’’

In a 1984 review of a show in West Newton, Globe art critic Christine Temin noted that Mrs. Arnold’s “large abstract canvases are sprayed and spattered with colors that swirl restlessly, like the movement of an ocean.’’

Mrs. Arnold, Temin said, also “uses intricate textures to suggest natural forms: ‘Tempest’ contains gritty passages of paint that read like complicated rock formations.’’

Choosing subjects for her artwork that were as expansive as her approaches to a canvas or a notepad, Mrs. Arnold drew and painted people and scenes she had observed in Boston and far across the country.

Painting Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, Mrs. Arnold employed a “pale softness’’ along the top, “as if we’ve lifted off into the heavens, each panel brushed with gauzy green and orange in strokes that read like hieroglyphs,’’ McQuaid wrote of a 1997 show. “Bottom to top, her work reads like a spiritual journey, rife with travail and unexpected clues to enlightenment.’’

These were not the leaps of imagination friends and family might have expected decades ago from Dorothy Quincy Warren, a debutante who was known to all as Doffie. In March 1943, she was photographed for the Globe dancing a rumba in the Copley Plaza’s Oval Room with her fiance, David B. Arnold Jr., before he left to serve in World War II.

Her father was Bentley W. Warren, an investment banker and a name partner in a Boston firm. Her mother was the former Dorothy Thorndike. The oldest of three daughters, Mrs. Arnold spent her first years in Brookline before moving with her family to Manchester-by-the-Sea.

“She grew up very conflicted about the privilege she had from an early age,’’ said her son, David of Boston, a former longtime Globe reporter.

“She would talk with me about this a lot,’’ he added. “She realized that privilege was very shallow, and took it with a grain of salt. She knew it was nothing but the luck of birth that put her in certain places.’’

Mrs. Arnold graduated from Beaver Country Day School and was at a social gathering when she met David B. Arnold Jr., a Harvard College student.

“Mom kept prolific diaries, and her diary just gushes about this guy she met at a dance,’’ her son said three years ago in an interview for his father’s obituary.

After marrying in 1943, Mrs. Arnold gave birth to her first child before the war ended, and had no time to pursue studies immediately after high school.

“I think to her dying day she was trying to play catchup because she had never gone to college,’’ her son said. “She tried very hard to always be aware of what was going on around her.’’

At 51, Mrs. Arnold enrolled as a full-time student at the Museum School. But throughout her life “she learned on her own,’’ her son said. “She learned French, Italian, and a little bit of German. At the dinner table or breakfast table we would have vocabulary tests, and we would speak different languages.’’

It was in her East Cambridge studio, though, that Mrs. Arnold created her own visual language.

“Her sketchbooks, shown here in a glass case, invite us to glimpse her process,’’ McQuaid wrote in her review of Mrs. Arnold’s 2002 retrospective. “She fills them with paint and text, inking her struggle of the moment onto each page, seeking salvation in image making. Landscapes and skyscapes built up with paint embody her soul’s journey. Trees become emblems of the self.’’

While painting and in all parts of her life, Mrs. Arnold could be a whirl of motion, which was reflected in each canvas. “Her art was just bursting with energy — enormous amounts of paint and light,’’ said Sarah Putnam, a friend who is a freelance photographer and writer.

Mrs. Arnold and her husband, who died in 2015, had been generous donors to Boston’s arts institutions.

A few years ago, her family created the Doffie Project, which has raised more than $250,000 for charities by selling her paintings — 80 percent of each purchase price goes directly to a nonprofit.

Her most personal philanthropy, however, took place when she opened her studio for children to use as an extracurricular arts space. She would set up tables for them and leave out paper for drawing and painting.

“She would work her way around the table and engage the kids one-on-one,’’ Putnam said. “Her passion for art and color was contagious, no matter what age you were.’’

Inviting children into her studio brought Mrs. Arnold “much joy,’’ said Andrew Holmes, who worked as her studio manager and assistant.

“Art was such an important part of her life,’’ he said, “and I think she recognized it could be an important part of other people’s lives if they were given the opportunity. She was a lovely human being.’’

In addition to her son, Mrs. Arnold leaves two daughters, Dorrie of North Granby, Conn., and Wendy of Los Angeles; her sister, Mary Gould of Bedford; three grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

Family and friends will gather to celebrate Mrs. Arnold’s life at 11 a.m. July 27 in Trinity Church in Concord.

Mrs. Arnold’s studio “was just an absolutely magical place,’’ said Holmes, who is Putnam’s son.

“She was sort of constantly on the move and tinkering,’’ he said. “She would pull out old pieces from years prior and decide, ‘You know, this actually needs some hodgepodge here or glitter there.’ I don’t think she felt that any of her pieces were necessarily finished. They were just done for now.’’

Bryan Marquard can be reached at bryan.marquard@globe.com.