To make sure Jerome Winegar knew he wasn’t welcome on the day he arrived as the new headmaster at South Boston High School in April 1976, some parents and students painted graffiti on the front sidewalk: “Go Home, Jerome’’ and “Winegar, We Don’t Want You.’’

He was there at the behest of US District Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr., whose desegregation ruling led to the court-ordered busing that turned the high school into a national symbol of racial unrest. Garrity placed the school under federal receivership, and then ordered the Boston School Committee to hire Mr. Winegar, who left a position as assistant principal of a St. Paul, Minn., junior high school to take what was arguably the toughest public school job in the country.

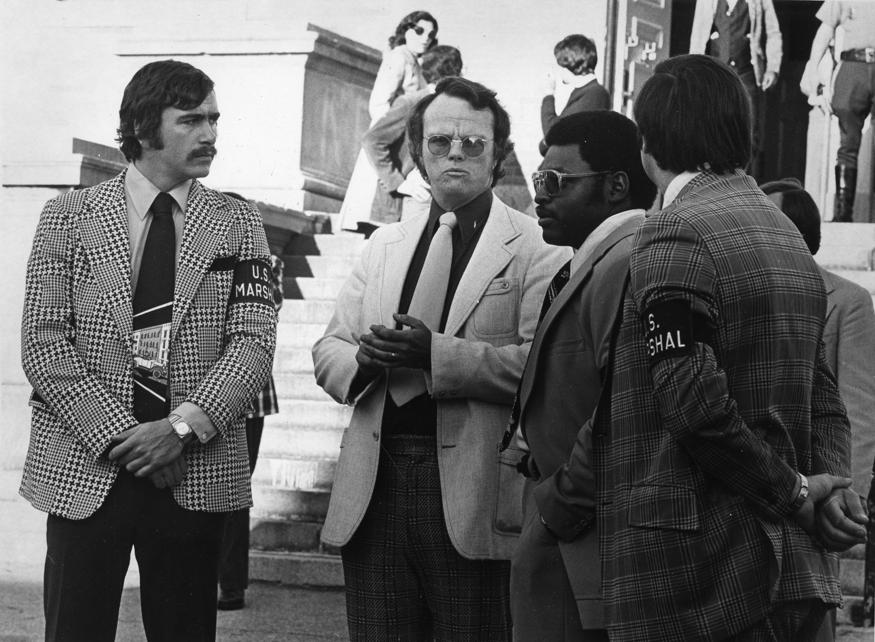

Gazing at students through tinted, gold-rimmed glasses, his curly hair spilling over his collar, Mr. Winegar slipped through a side door on his first visit, sidestepping the graffiti. The day before, South Boston parents had jeered him when — escorted by three police officers — he held a news conference elsewhere in Boston, in a narrow hallway outside the schools superintendent’s office.

“I believe that a person has a choice of where to make a stand and this was my stand. They thought I was going to leave. They wanted me to leave. But I stayed,’’ he told the Globe in 1989, when he stepped down as headmaster, adding: “It has been the most exciting 13 years of my life.’’

Mr. Winegar, who after South Boston High served as a school administrator in Boston, Methuen, and Springfield, died in his Springfield home June 1 of colon cancer that had metastasized. He was 78.

“He was an ordinary man who wanted the best for all children,’’ said his wife, Belcanto Hammond.

Those were not ordinary times, however. Mr. Winegar lived under tight security, and federal marshals initially moved him from a Newton hotel when antibusing demonstrators began picketing outside. A School Committee member called for his ouster as soon as he arrived. South Boston parents petitioned for his removal, rejecting him as an outsider and complaining about his memberships in the NAACP and American Civil Liberties Union.

He endured student boycotts early on, and during part of his time leading South Boston High, those who entered the building passed through metal detectors. Mr. Winegar himself was accompanied by a full-time bodyguard. “I wasn’t a headmaster,’’ he told the Globe in 1989. “I was a firefighter trying to bring the blaze under control.’’

He did so with assistance from some faculty, parents, and students, and from officials such as Raymond L. Flynn, who was elected to the City Council and then as mayor during Mr. Winegar’s tenure. “Whenever there was a serious problem in the school, I would always call him, and within 30 or 40 minutes he was on the property,’’ Mr. Winegar recalled in a 1983 interview. “He would walk the halls, he would sit in the cafeteria, he would talk with black kids or with white kids. He did whatever would help.’’

When Mr. Winegar left the South Boston headmaster job, Thomas Atkins, a Boston NAACP official who was a central figure during desegregation, told the Globe that “the whole city, particularly the parents of school-age children, owes him a tremendous debt of gratitude.’’

Atkins added that “at a time when the city was going through its most turbulent era, much of it centering around South Boston High School, Winegar was a rock. He stood firm and stood with and for the children. He protected them from other children who wanted to raise hell and from adults who should have known better and wanted to raise hell.’’

“He has given students at South Boston something they never had before — a bright future,’’ John O’Bryant, the first African-American elected to serve on the Boston School Committee, told the Globe in 1989.

Born in Kansas City, Mo., Jerome Clark Winegar was the oldest of three brothers and grew up in Independence. His father, James, was a plant representative for General Motors, traveling to dealerships. His mother, the former Evelyn Clark, was a homemaker.

Mr. Winegar was an Eagle Scout and entertained thoughts of becoming a professional in the Boy Scouts organization. His mother’s sister was a teacher, though, and she inspired him to think about a career in education. “I remember when I was a kid, other people gave you toys. She always sent me a book,’’ he told the Globe in April 1976.

Even as a teenager, Mr. Winegar “always was driven to make a difference,’’ said his brother Richard of Belleville, Ontario. “He was always questioning everything around him. He always wanted to understand. If he saw something that didn’t make sense to him, he had to question that.’’

Majoring in English and minoring in physical education, Mr. Winegar graduated with a bachelor’s degree from what was then Central Missouri State College. He also received a master’s in education from Central Missouri and helped pay his graduate school costs by working at a J.C. Penney store.

He taught English at a high school in Kansas City before moving to St. Paul, where he was assistant principal at Wilson Junior High School. Mr. Winegar was 38 when he was offered the job in South Boston.

The work in Boston took a personal toll. “It probably cost him his first marriage,’’ his wife said. “It probably cost him his second marriage, too.’’

In 1990, he married Belcanto Hammond. The years since “were blissful years,’’ she said. “He just was a quiet man, but he wanted equality.’’

Mr. Winegar continued to serve as a Boston Public Schools administrator for several years after stepping down as headmaster, working to develop a 13th-year program for seniors who weren’t yet ready for college. Then he worked at Methuen High School and the High School of Commerce in Springfield before retiring in 2000, his wife said.

“He was a very ordinary guy with an extraordinary commitment to making a difference,’’ his brother Richard said.

In addition to his wife and brother, Mr. Winegar leaves two sons, Jerome D. of Port Townsend, Wash., and Jonathan of Hyde Park; another brother, Steven of Madrid; six grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held at 2 p.m. Saturday in the Schwartz Campus Center Auditorium at American International College in Springfield.

Asked by a Globe reporter a year after arriving in South Boston if, knowing what he did then, he would still have taken the job, Mr. Winegar replied with a simple: “Sure I would.’’

“Most people ignore me when I walk down the street,’’ he said in that July 1977 interview. “Sometimes someone yells, ‘Go home, Jerome.’ I turn around and wave, and get a smile.’’

Bryan Marquard can be reached at bryan.marquard@globe.com.